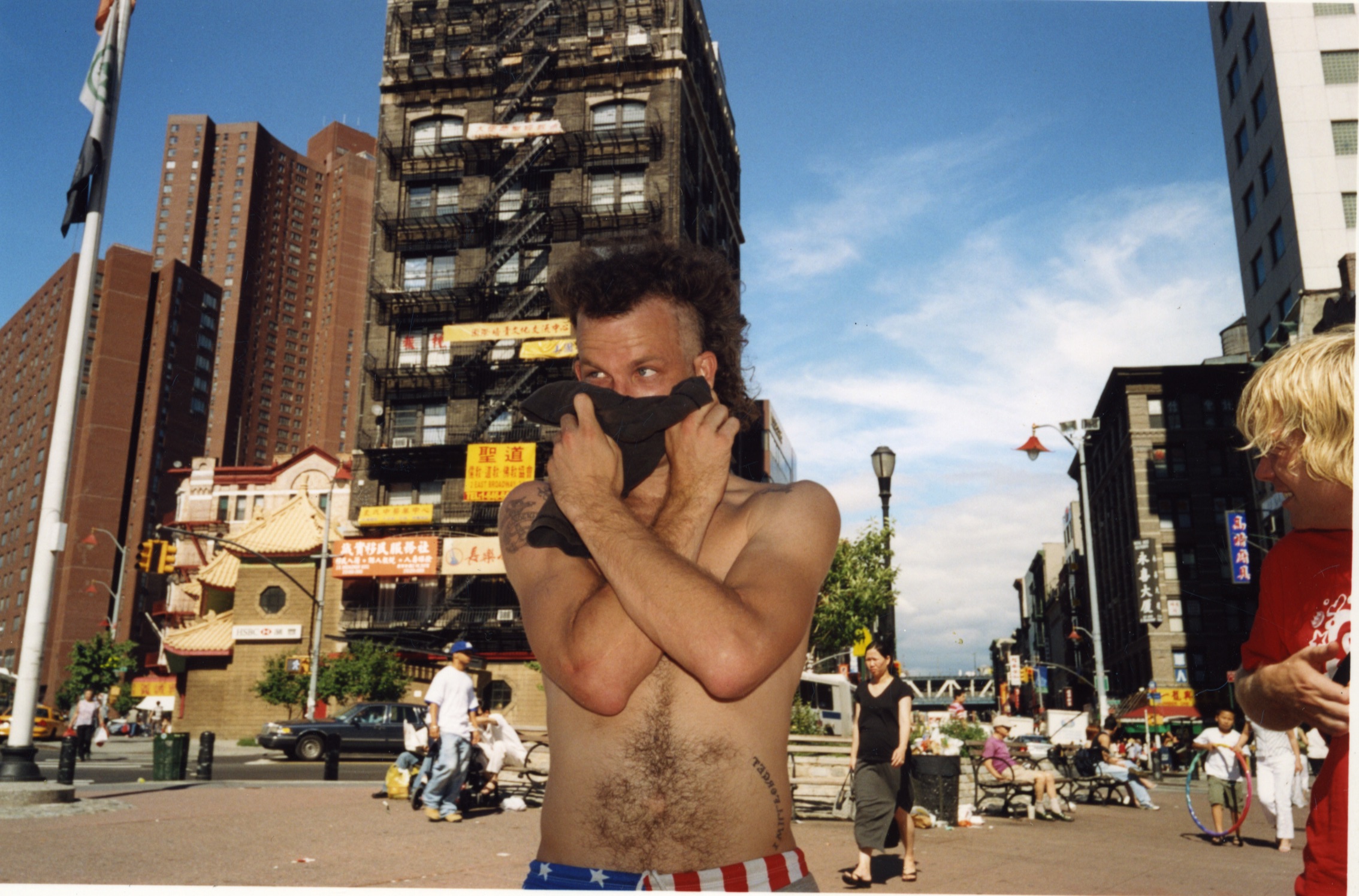

Alain Levitt’s Time Capsule of Early Aughts NYC (2000-2005)

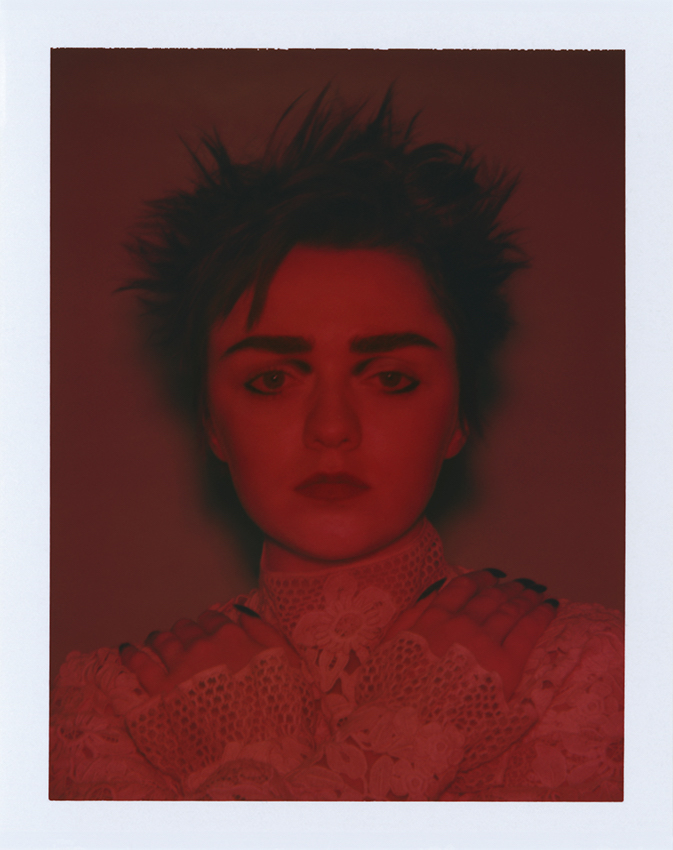

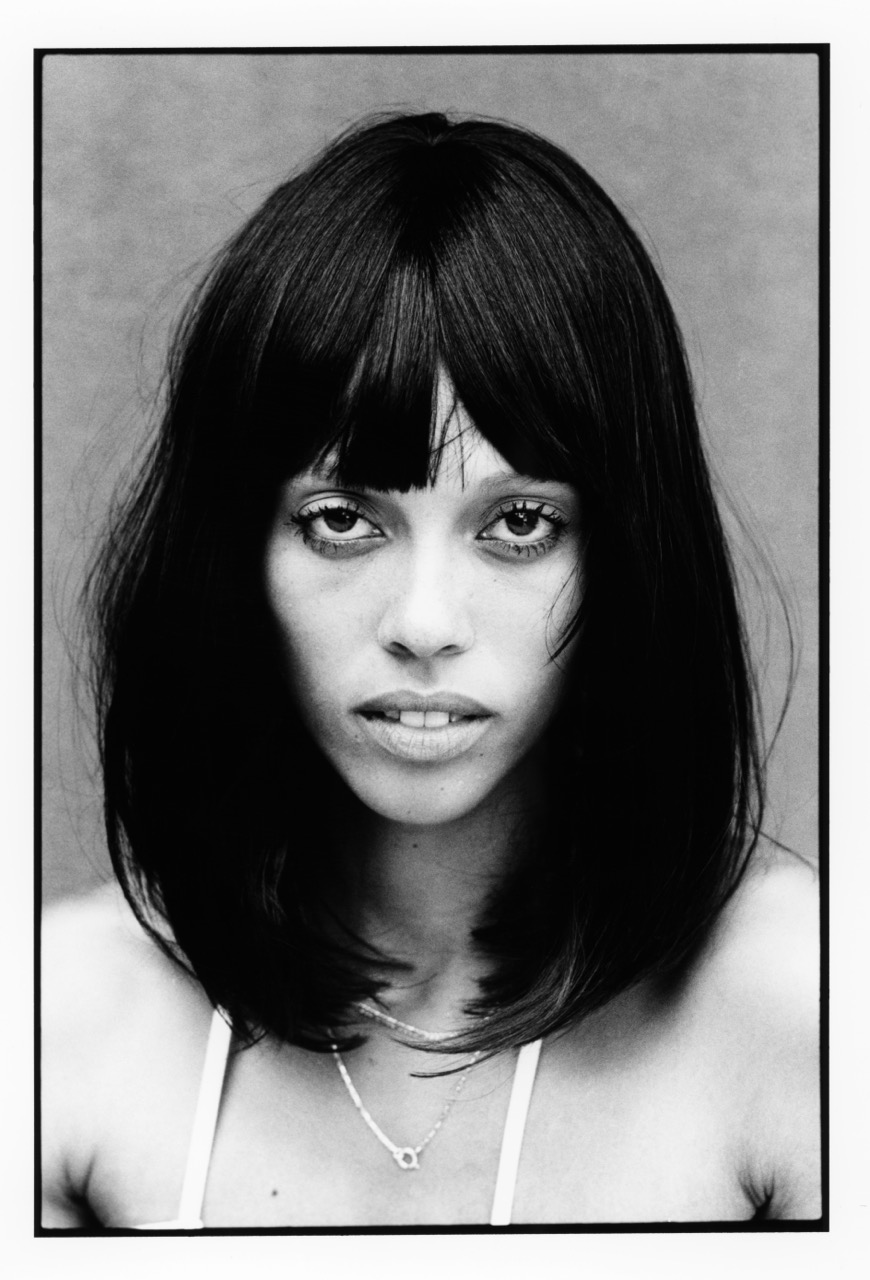

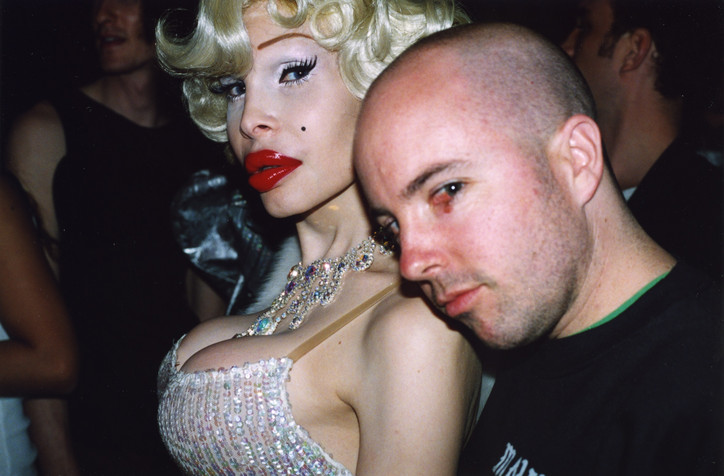

Amanda Lepore, Alain Levitt

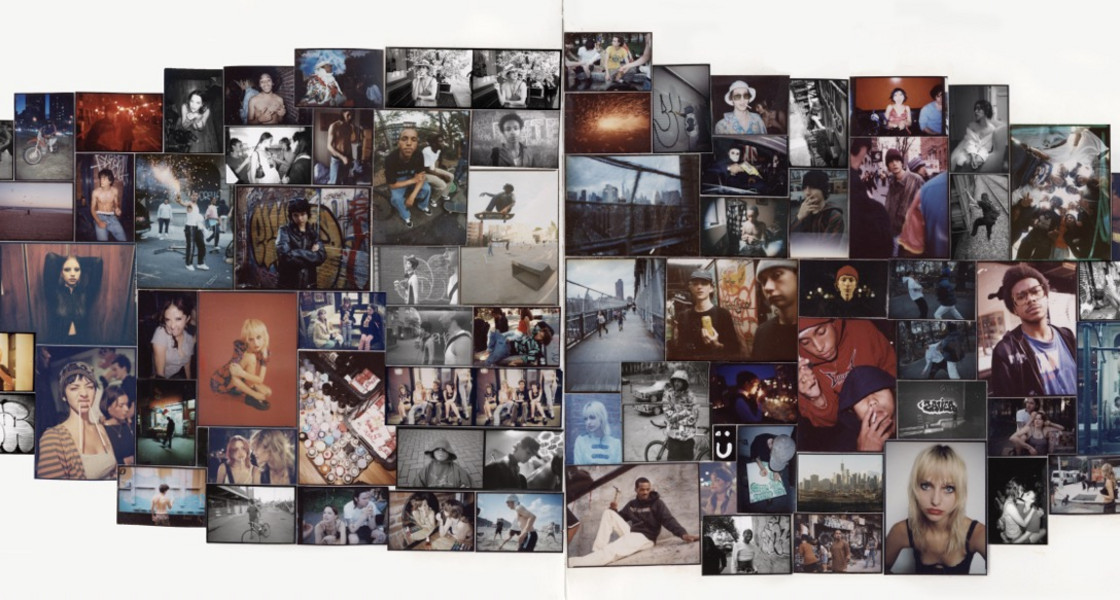

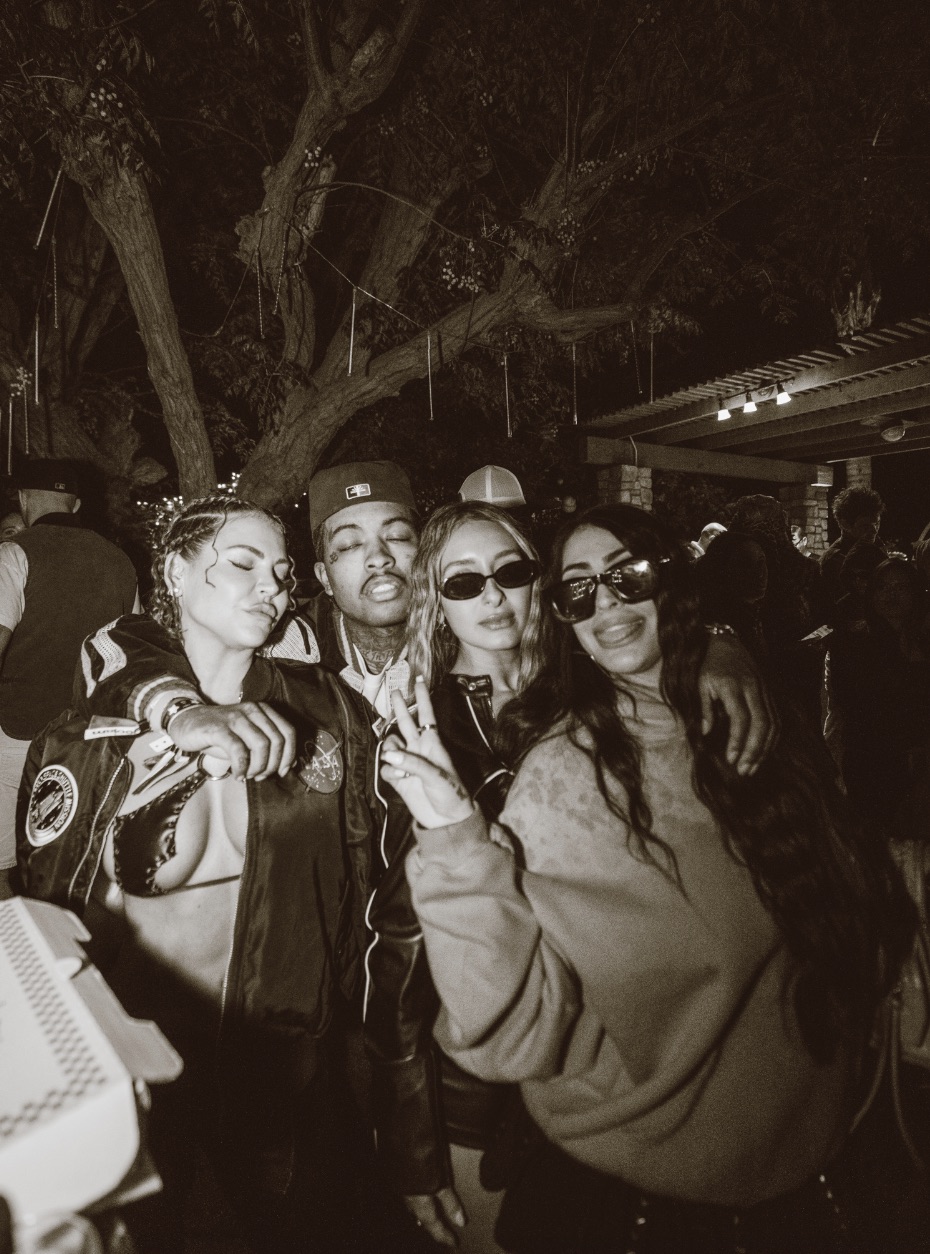

Beyond the exhibition, Alain’s book of the same name, available May 1st, acts as a time capsule, a snapshot of what he and his friends were getting into back then — figuring their lives out, meeting people, making memories and now, reminiscing on what was. Today, walking through Dimes Square where his and his wife’s restaurant, Bacaro, has become a premiere meeting hub for the neighborhood's youth, Alain recognizes that while “it’s such a different world,” youth is still the same.

“Young people are young people, man. It’s different being older and not really understanding what’s going on. I don’t fully feel like I’m part of it in the same way… but I love it and it seems the same, but one thing I see is it’s more colorful, it’s animated, and everything seems kind of to an extreme that I really love.”

When Bacaro first opened in 2007, there was no Dimes Square. He likens the emergence of the neighborhood to “the beginning of Williamsburg when that kind of popped off and all of a sudden, if you went down Bedford, it was just young people everywhere and everybody was dressing outrageous.” Back then, congregating in Bedford symbolized a communal rejection of Manhattan. What Levitt witnesses in Dimes, a neighborhood that’s become a bit polarizing amongst New Yorkers, is “more or less the same thing” — though the object of its rejection seems yet to be defined.

Perhaps it’s more of an acceptance — of indulgence, of being part of something, of embracing the past, keeping alive this idealized perception of NYC.

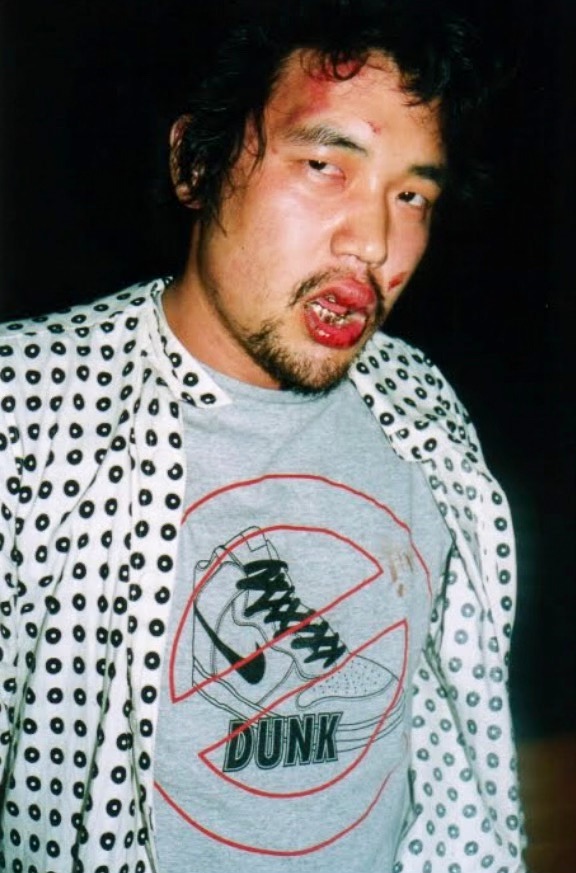

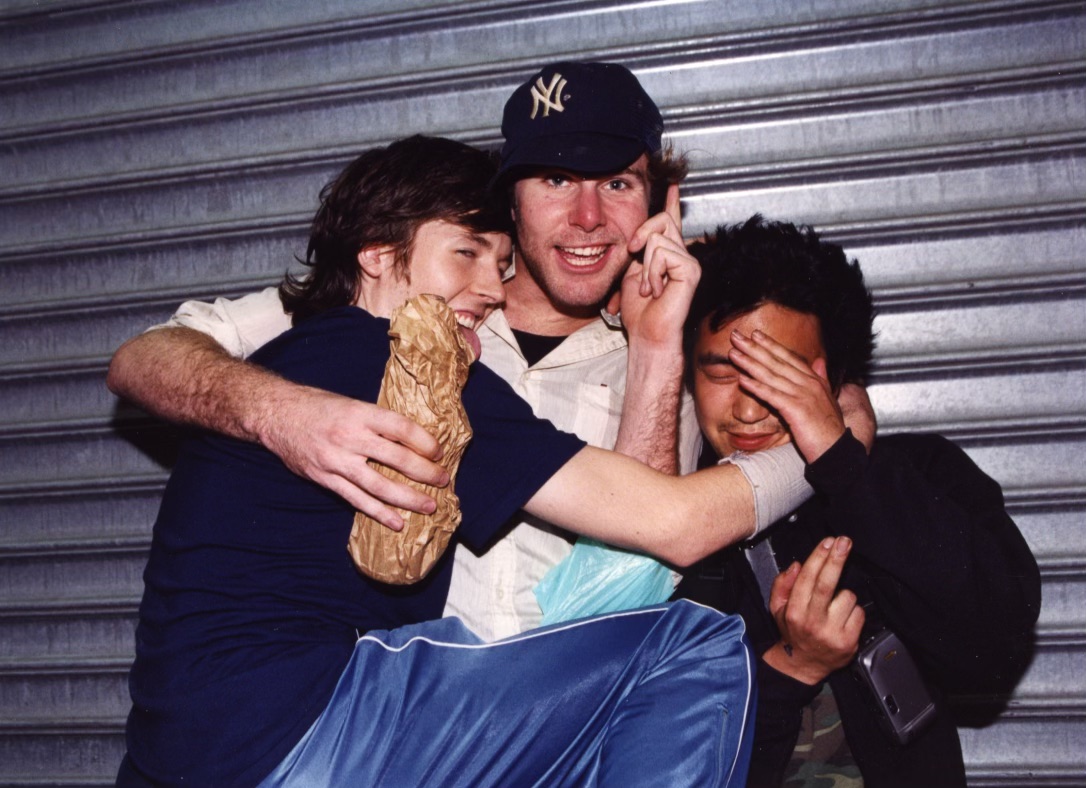

left to right - Ryan McGinley, Dan Colen, Kenji Ukigaya, Dash Snow

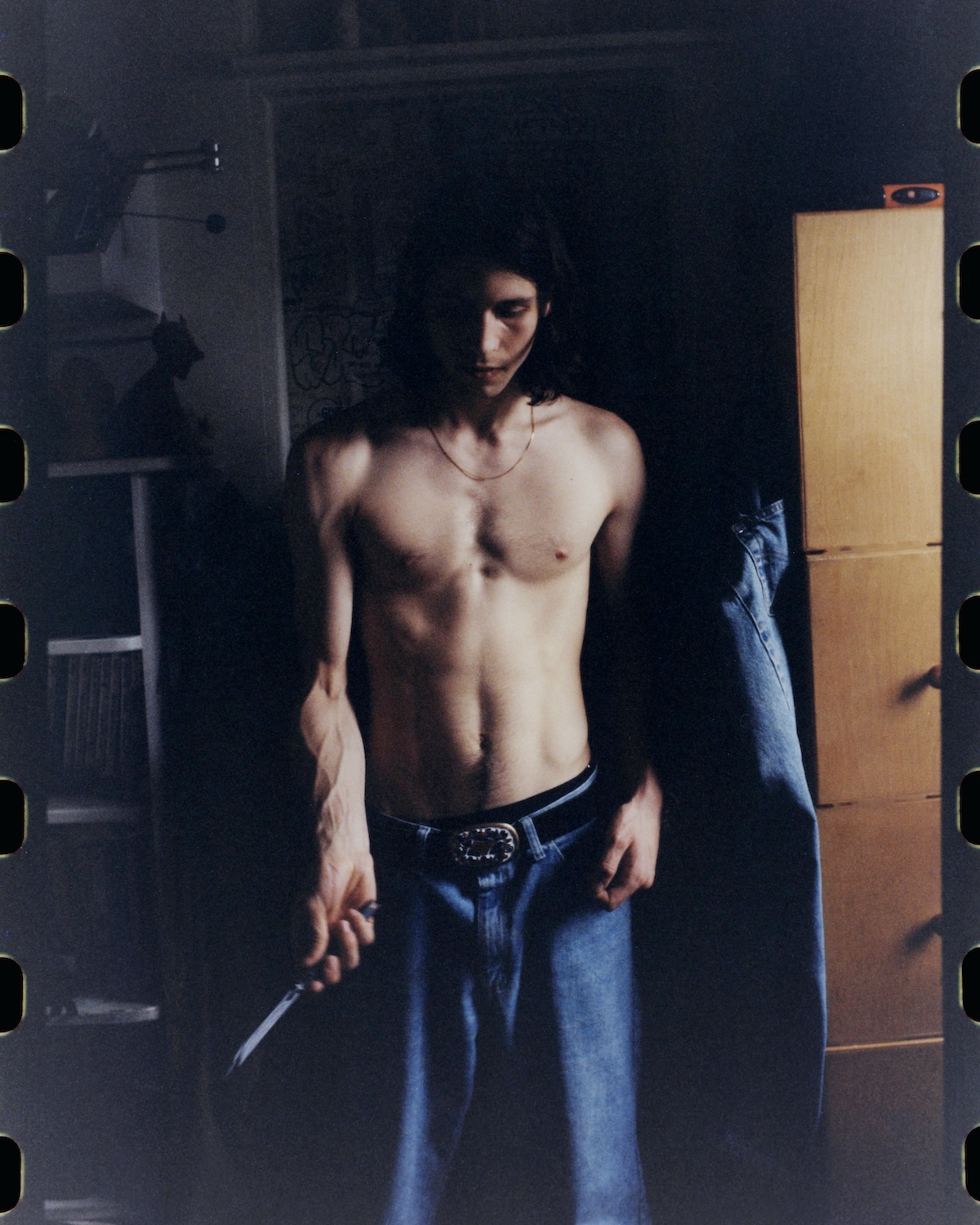

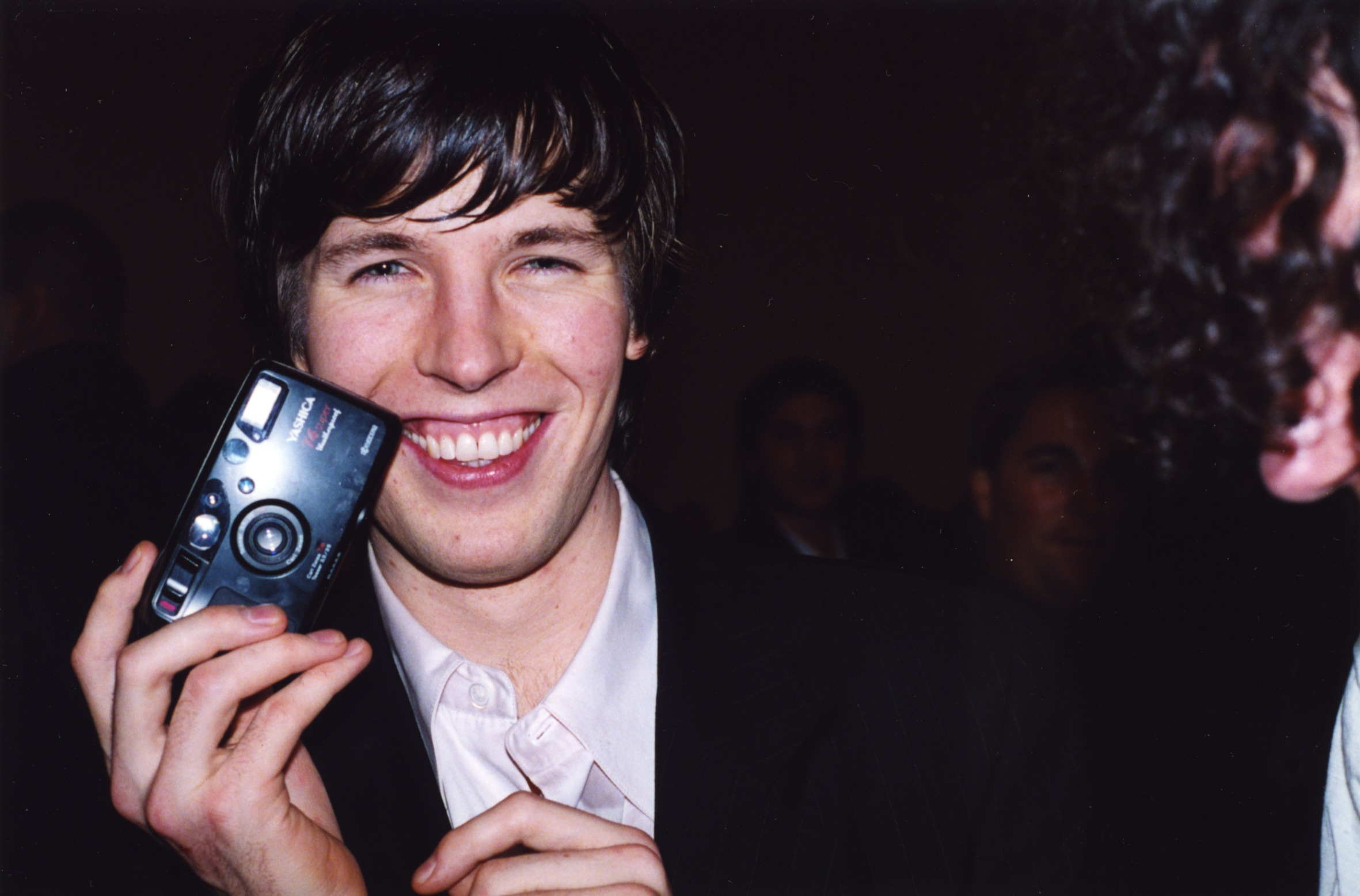

When Alain moved out here in the ‘90s, his older sister Danielle gave him a camera. At that time, he didn’t consider himself a photographer. He was just a younger brother emulating his older sister, who was shooting street photography and fashion parties for the Post. Alain recalls “showing up to Max Fish and being gently made fun of for his oversized paparazzi rig.” For his second job, Alain was working as a bar-back at The Cock and The Fat Cock (now known as The Hole), giving him “a front row seat to a wild NY that was quickly being choked out by Mayor Giuliani.”

On one of his first nights, he was assigned to the back room at The Cock, where patrons would do whatever drunk people do in the dark. As a kid “brand new to New York” flashing a light on people, he realized that suddenly, his life was completely different. And it was exciting. “I made more money than I could have ever imagined. I was working minimum wage jobs coming from LA, at movie theaters and all this other shit. In NY, I was able to live off two days a week which gave me room to do everything.”

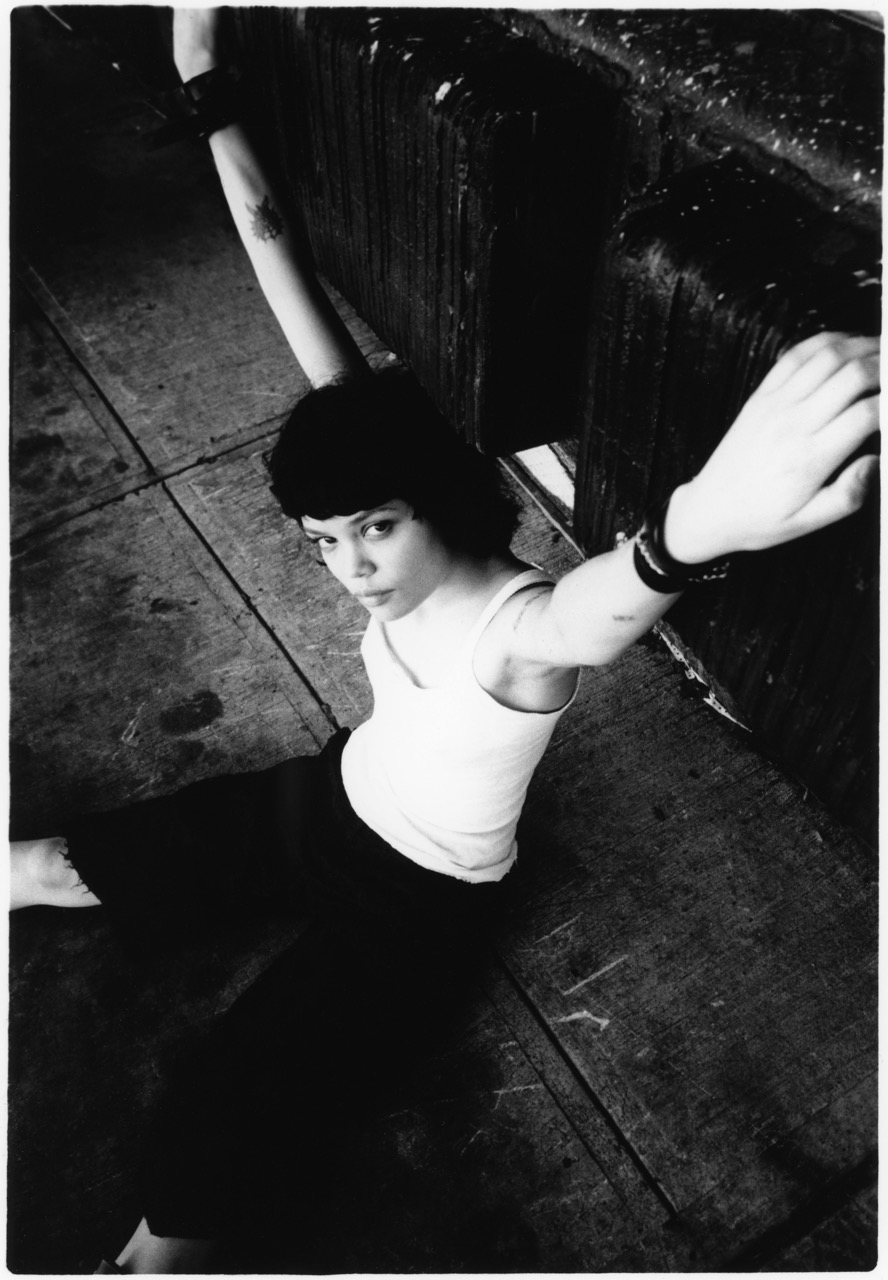

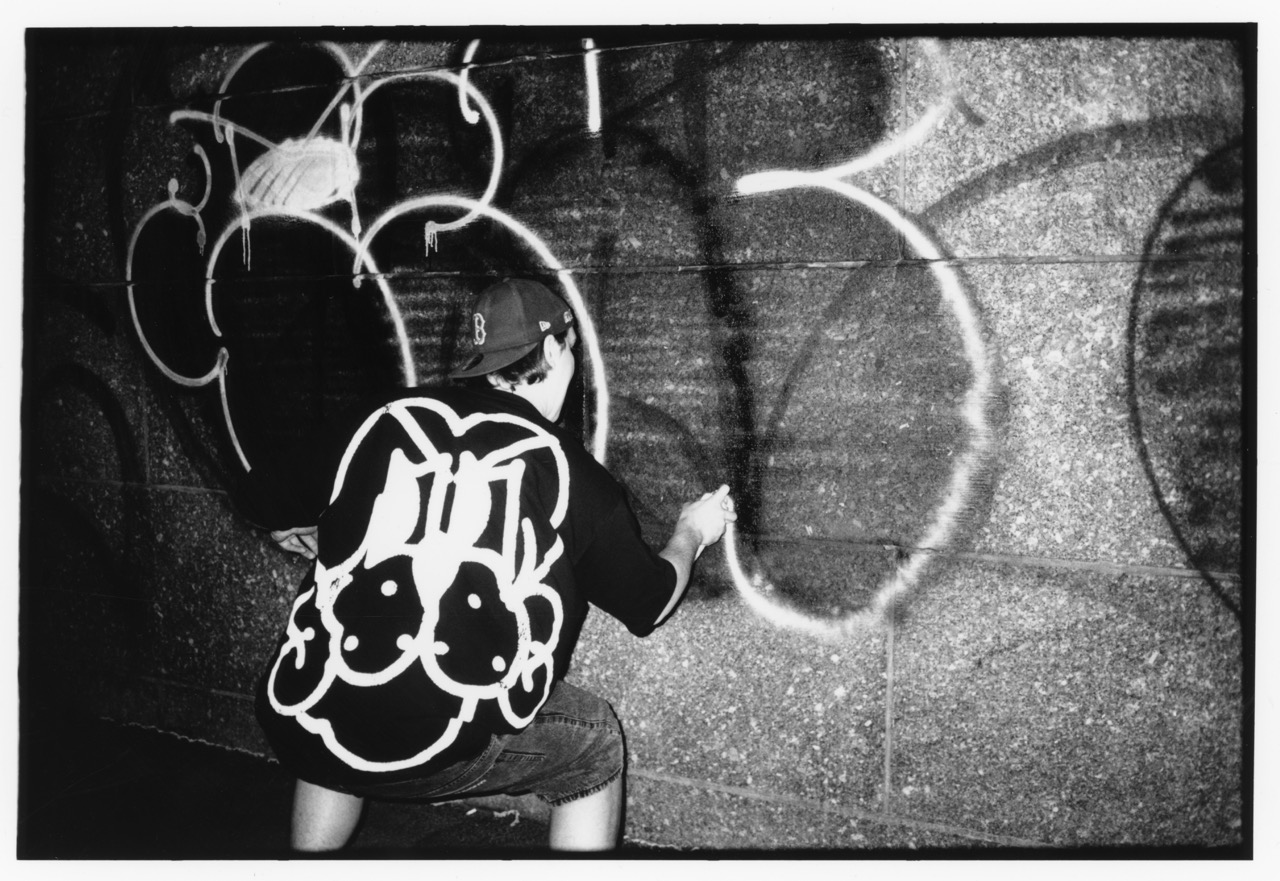

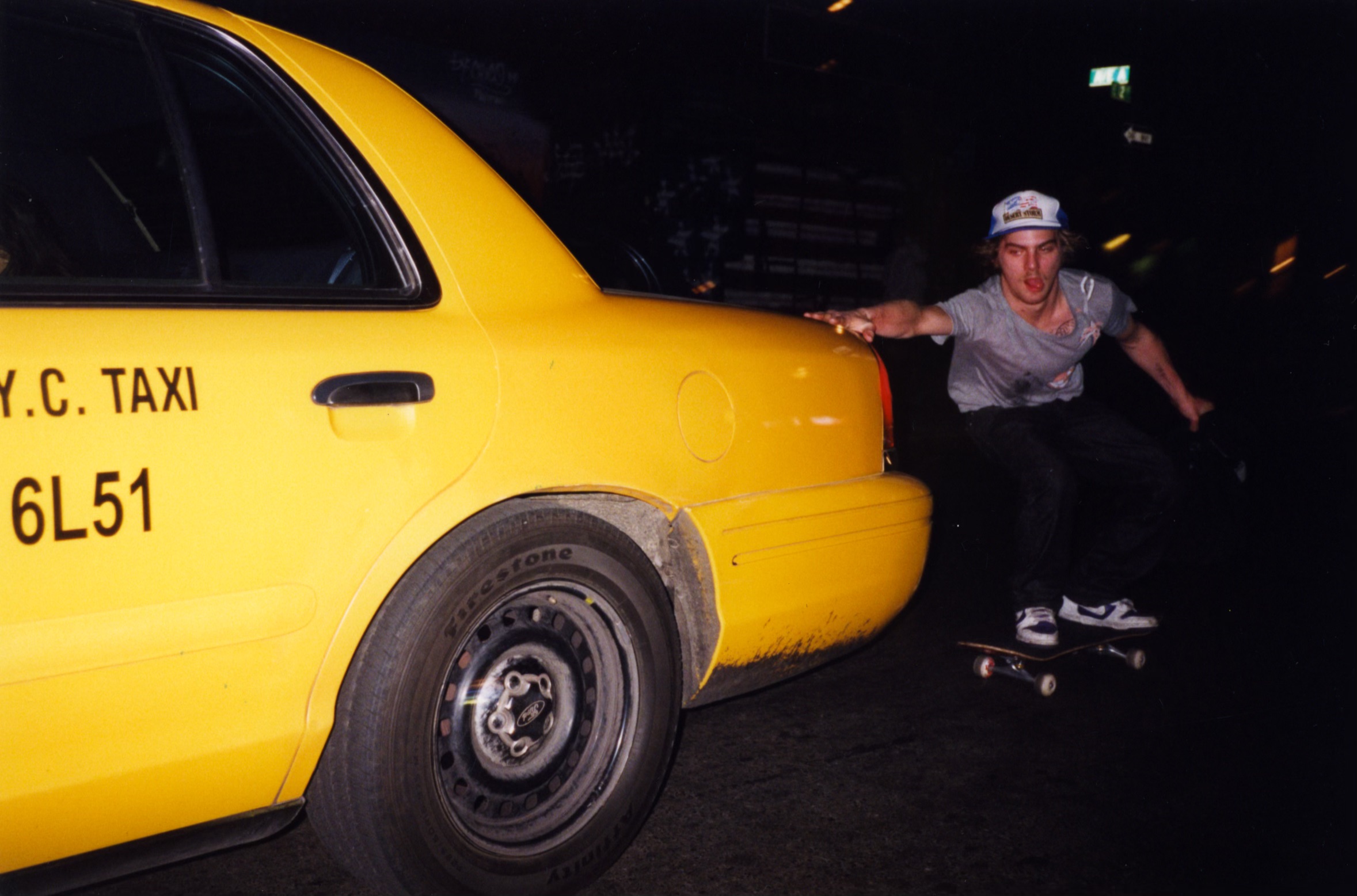

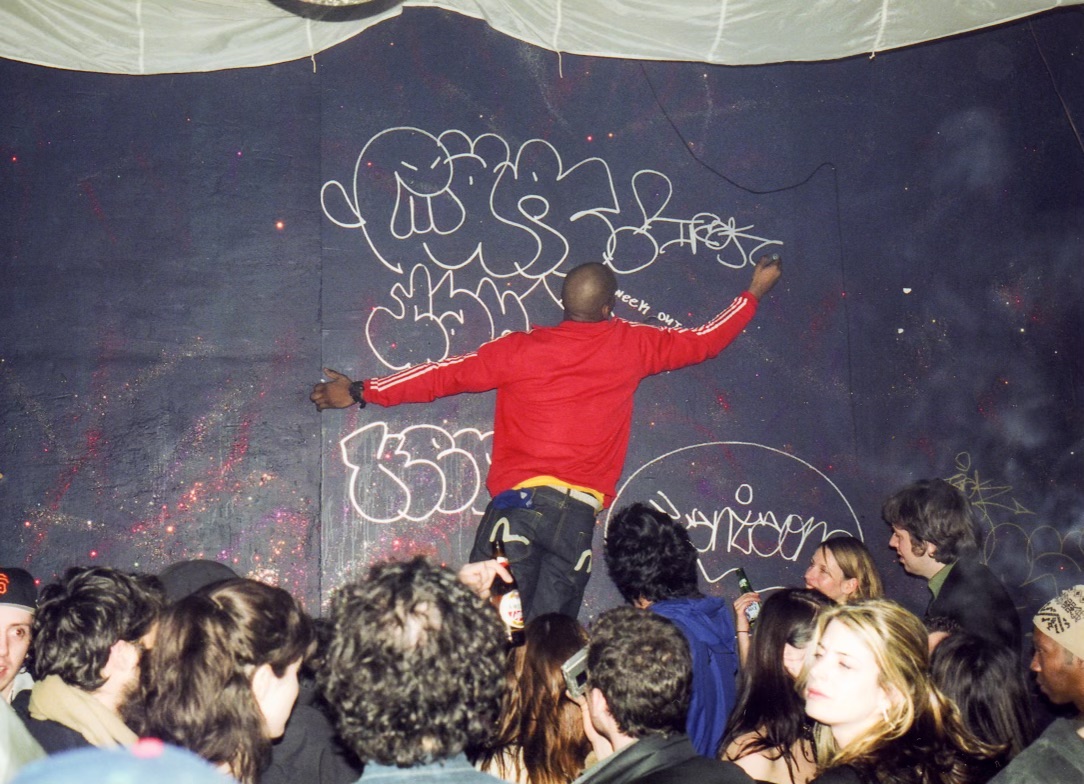

Eventually, Alain started shooting for Nylon, PAPER, V Magazine, and other publications on his days off. Though they didn’t fully feel like a part of that world, he and his friends (skaters, graffiti artists, ravers, the trifecta of '90s subcultures) disrupted the fabric of the fashion scene. Reminiscing on some of those moments, he tells us, “Our group would show up at the fashion parties and make our presence known, even though they probably didn’t think we belonged there, that maybe we hadn’t earned it yet.”

left to right - Ryan McGinley, Chloë Sevigny

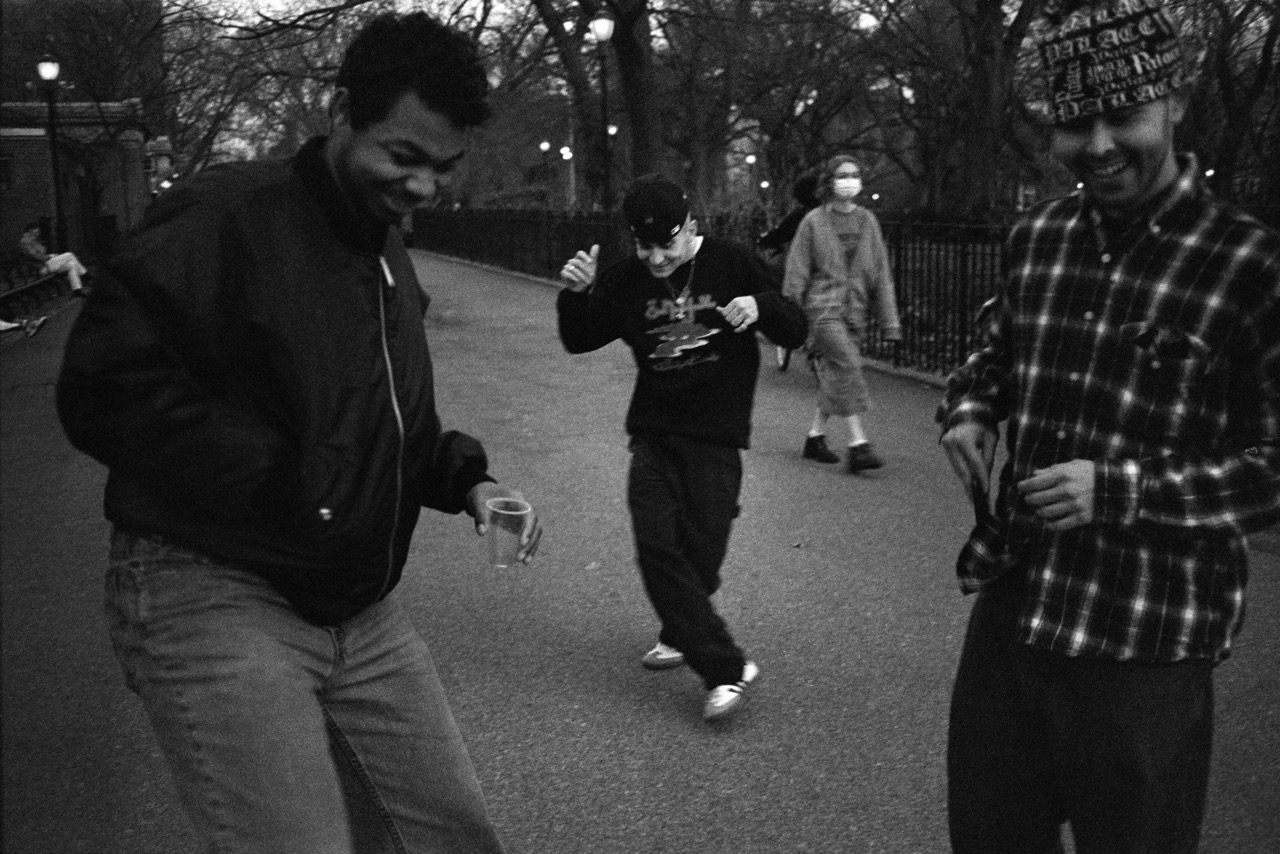

Then, Alain found his community on the Lower East Side, “Alife by day, Max Fish at night,” and “after starting a bi-weekly party, with Spencer Sweeny, at The Hole, planted his seed in the downtown scene.” The world that Levitt found himself navigating in his early years in New York City wasn’t new, it was itself a continuation of the pseudo-renaissance that emerged downtown in the ‘60s and again in the '70s and again in the subsequent decades. “It’s almost like a 10-year cycle and one good thing about New York is that it lets you be young a little longer. We were coming out here thinking about the CBGB’s era.”

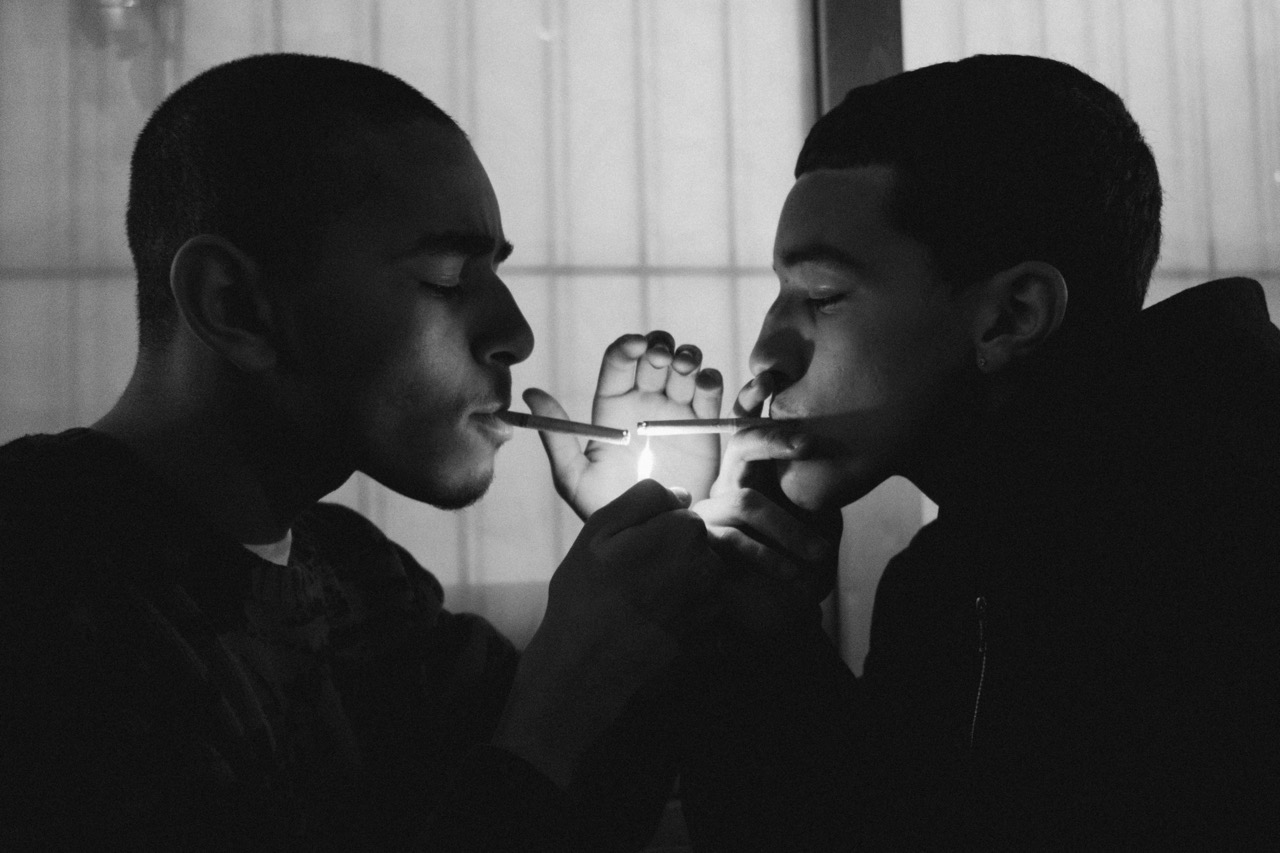

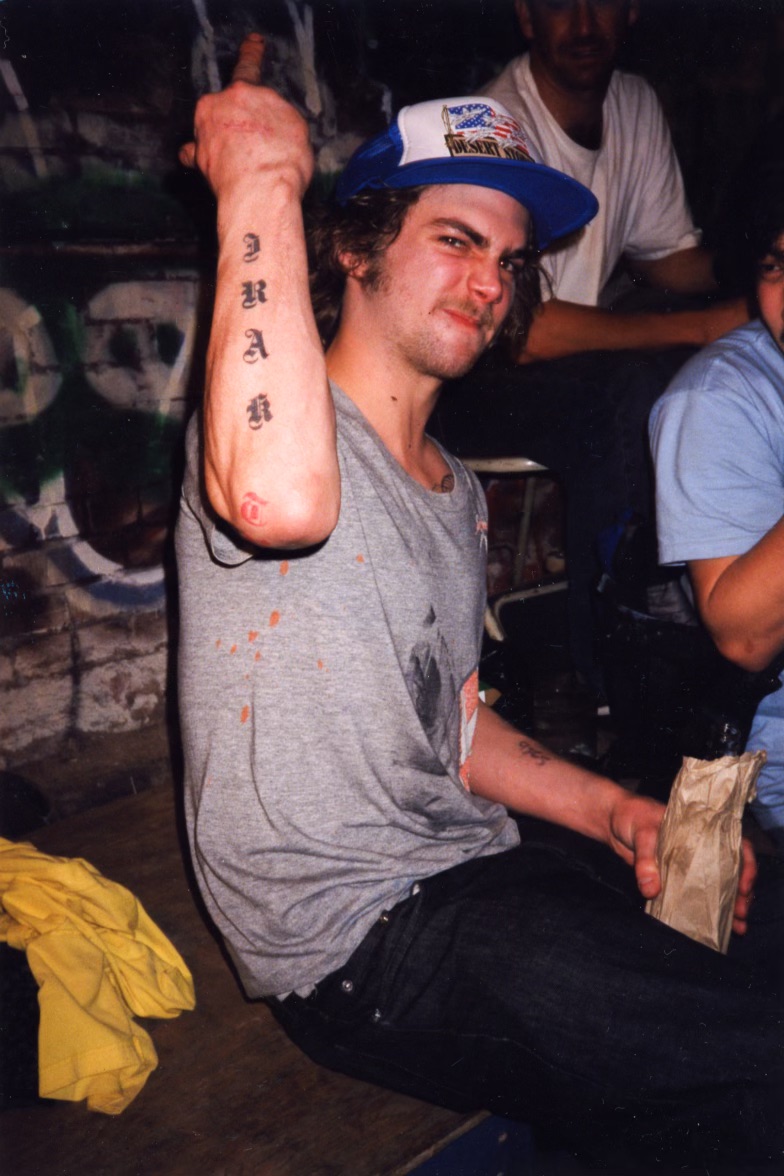

And when looking through Alain’s photos, while humming with an inherent sense of nostalgia, it feels as if these images could’ve been taken yesterday. Skateboarding, bands playing one-off shows in dingy music venues, gallery openings that pour out onto the block, it’s all still here, just slightly different. While the internet has made us more connected, and distractions more frequent, much of what was, still is. And for Alain, there’s an innate resilience to this culture of “youth”, a culture somehow driven by a shared dysfunction. “Living in New York is so hard, rents are high, the weather is hard. It can be amazing but you have to put up with all this other bullshit to get the best out of it. You have to be willing to suffer. The people that I knew and the people that I connected to and was around — there was always a certain amount of fucked-up-ness we all shared.”

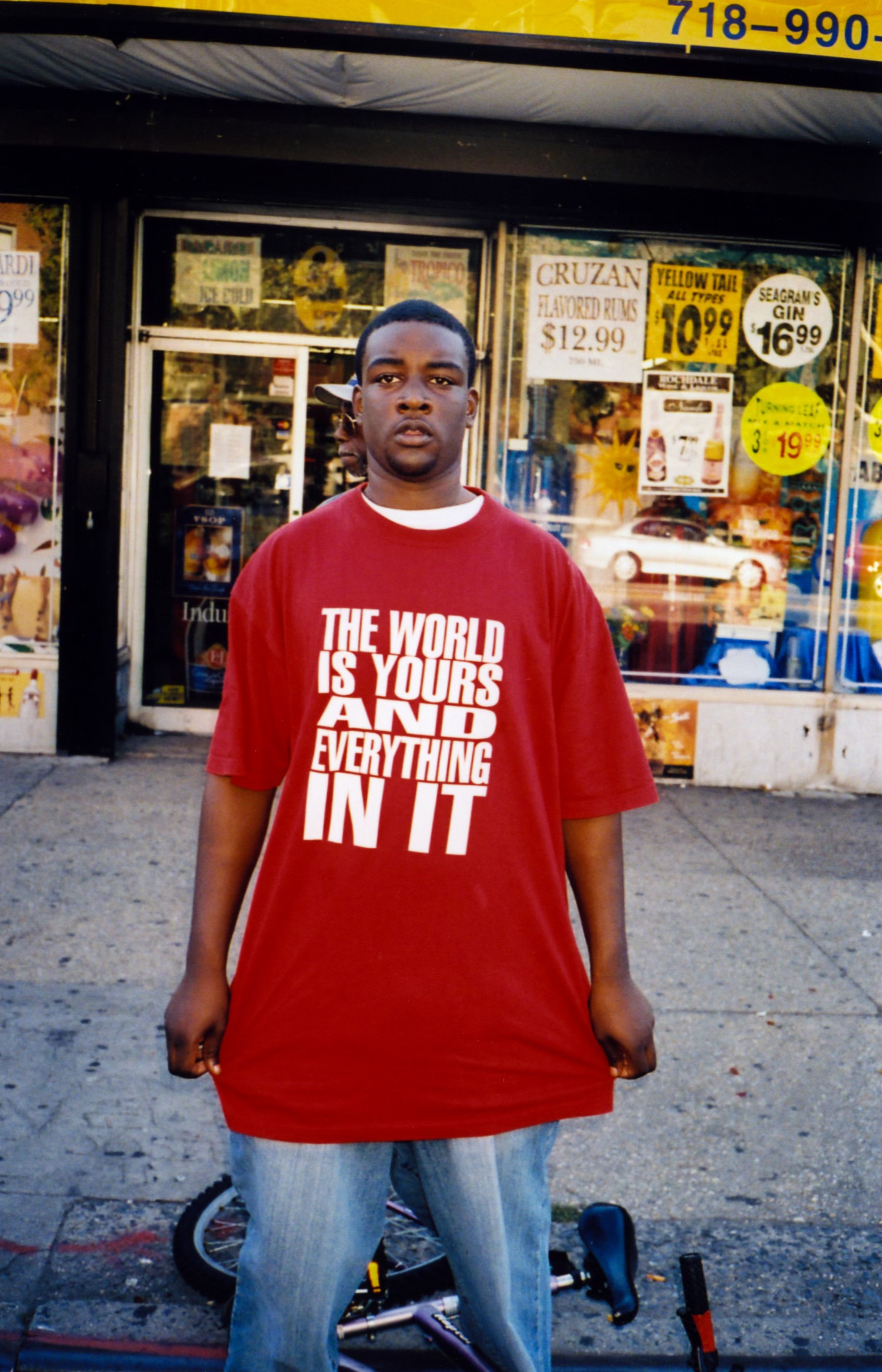

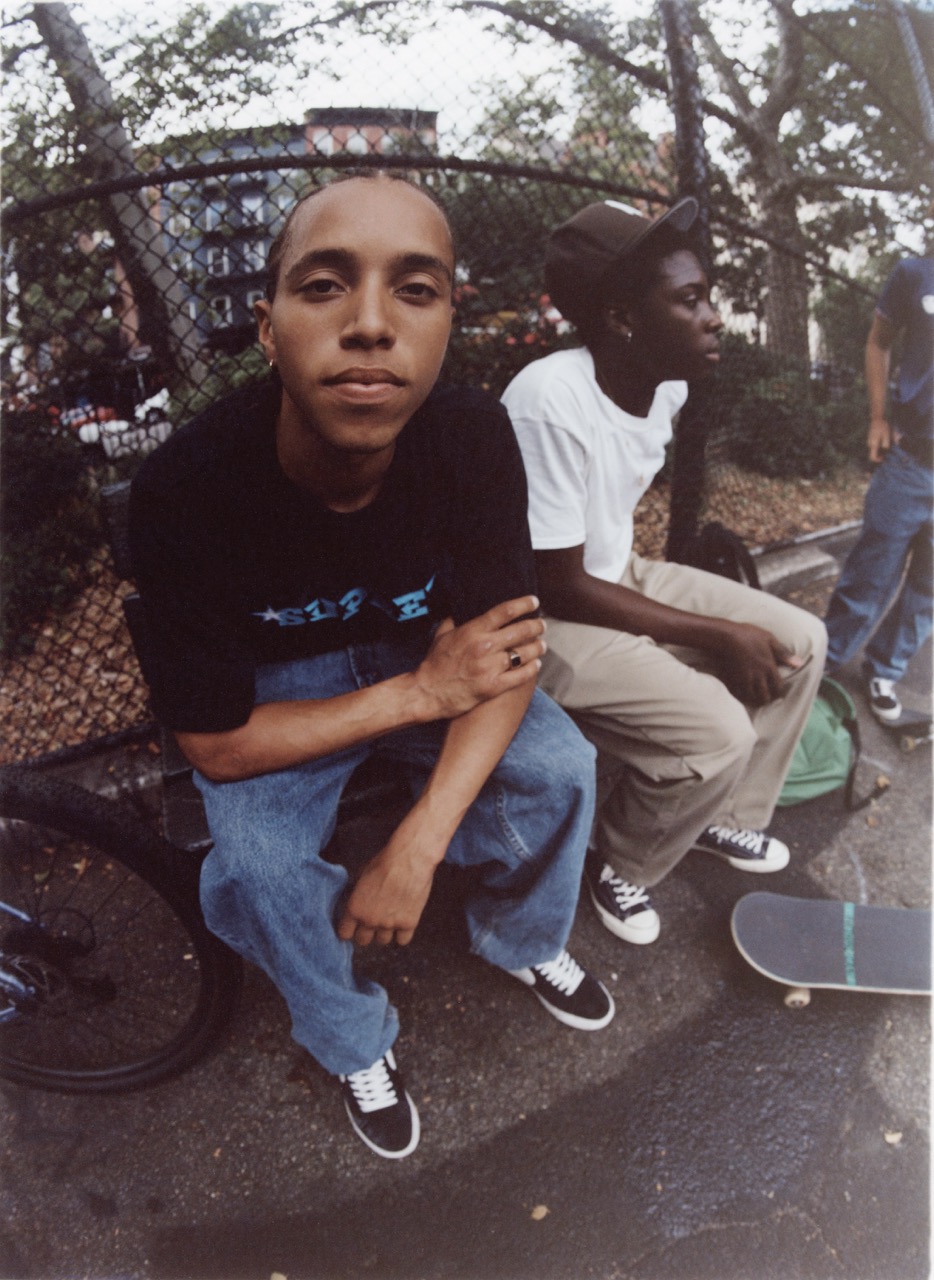

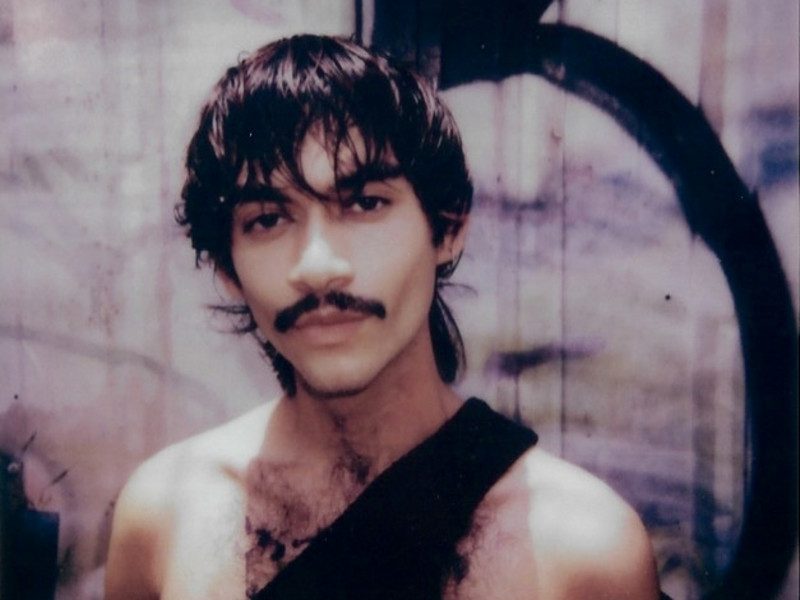

left to right, Dash Snow, Kunle Martins (Earsnot)

Whether seeking self-discovery in New York City, escaping a toxic family, or generally curious to explore the city’s burgeoning underbelly, people here find their own, often forming surrogate families along the way. Levitt’s book, and the photographs on display at WHAAM! exemplify that family isn’t always clean-cut and you might bond with a person you’d least expect to: on the train, at a bar, laying on the grass at Seward Park, skating at Tompkins, or having a plate of squid ink pasta at Bacaro before heading to Le Dive for some overpriced house wine.

In the most ordinary moments, the greatest ideas and connections can spring to life and this was true even then. “I imagine creativity drives a lot of this,” Levitt says. “There’s a thread that we saw and maybe even idealized New York City to be.” It’s a thread that this generation hasn’t seemed to let go of: “I feel like my book shows our moment of coming into ourselves and now the kids today are doing it themselves. In 20 years, there’ll be a record of their time that the next group of kids will be looking at. It might not be the same, but the roots are.”

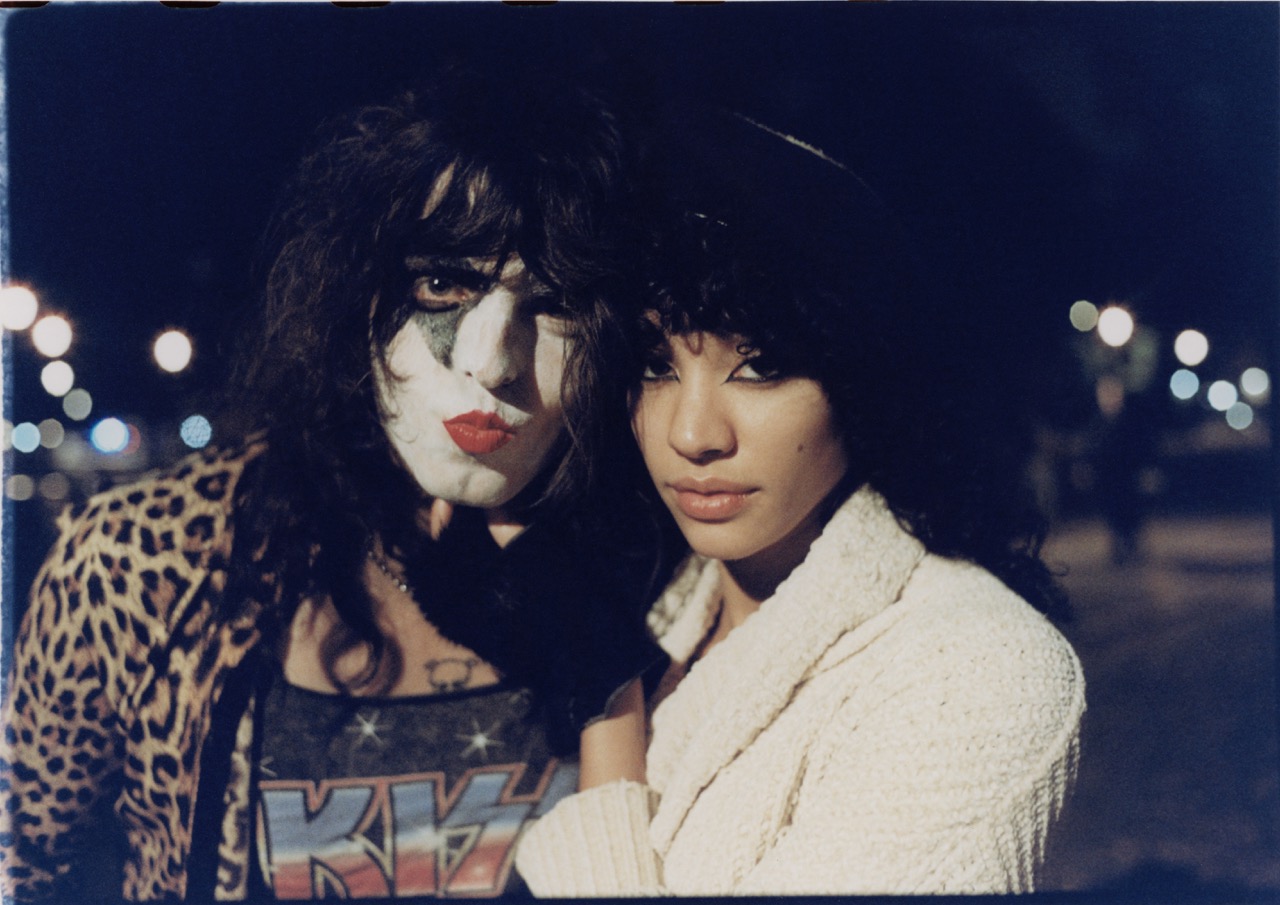

From Tim Barber, a former photo editor at Vice who edited the book, to Jesse Pearson, former EIC at Vice, Su Barber (Tim’s sister), Mike Piscitelli from Fucking Awesome and skateboarder Jason Dill, everyone involved in the book “from the editors down to the publisher was there in our circle, and pretty much all in the book too.” To Alain, everyone in the book was of equal significance, whether celebrity Chloe Sevigny or Marc Razo of Max Fish, who Alain recognizes as “a loving, wonderful person who’s been in the downtown scene forever.”

“Some of those people have definitely become legendary, which is awesome,” says Levitt. “But with them, it’s like me, I felt special to be there. I wanted to be with these people and we all had all of these lofty ideas of ourselves that were shattered over time. I think it’s good to break through those delusions of grandeur and get a real sense of what the world is. But at that moment, it was pure. We all thought we were special.” And maybe we still do.

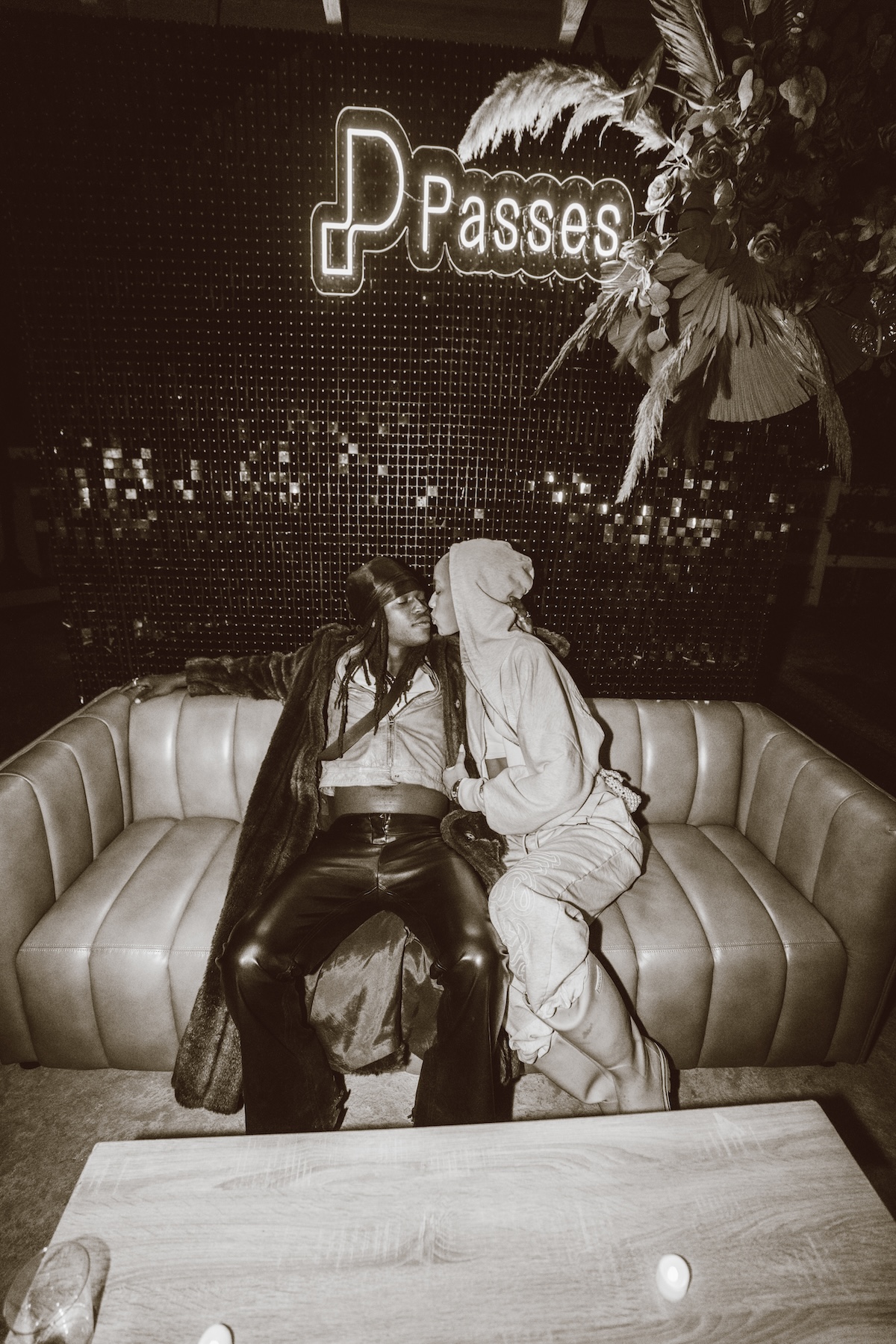

NYC 2000-2005 is on view April 18 - May 25, 2024 at WHAAM! at 15 Elizabeth St # 113, New York, NY 10013.