A Curator's Perspective: Alexander May Speaks With Spencer Daly

Alexander May– So, is that all the pizza that you've ever eaten?

Spencer Daly– That’s some of the pizza I’ve eaten.

AM– There's like 40 boxes, right?

SD– The stack actually goes around and over my desk as well. I think there's closer to 100. I can't fit anymore so I have to throw them out now.

AM– And you were saying that they're connected to your first show right?

SD– When I did what I call my first show, a rogue trip to Paris during Men’s fashion week, I spent two months trying to figure out how to build and ship four chairs to a tiny Paris showroom in the Marais. I ended up taking each piece apart and flying with four suitcases. During this time, I was so focused on working that every day I ate the same lunch – a slice of Sicilian pepperoni pizza from Pizzanista down the street. But yes, this pizza is now forever linked with the taking apart, packing, and traveling with my work.

AM– It was really kind of like modularity.

SD– I hate modularity, the word, because I went to architecture school and that was a kind of architectural masturbation. Modular is a little too clean for me. It makes too much sense. I see my work more as singular – objects that can’t be split.

AM– So you wanted your work to be able to travel essentially. That's how you’re connecting these different materials and utilizing that as a structural basis to make form in a way.

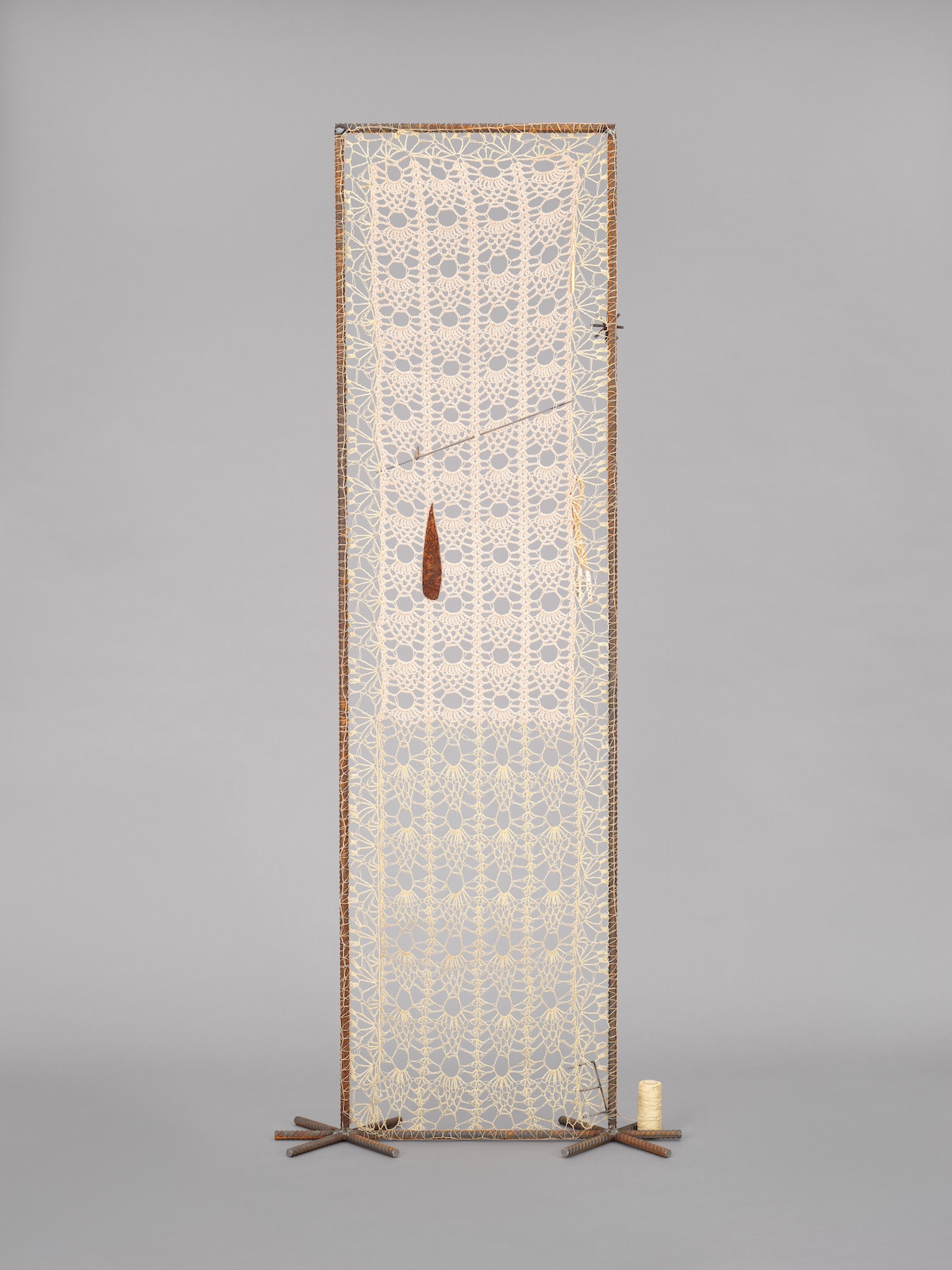

Do you think about ornamentation? Like with the abundance of detail in the new cabinet piece? There's not one or two locks, but fifteen. There is a lot of that in your work – you polarize something and then expand it until it becomes almost like a texture.

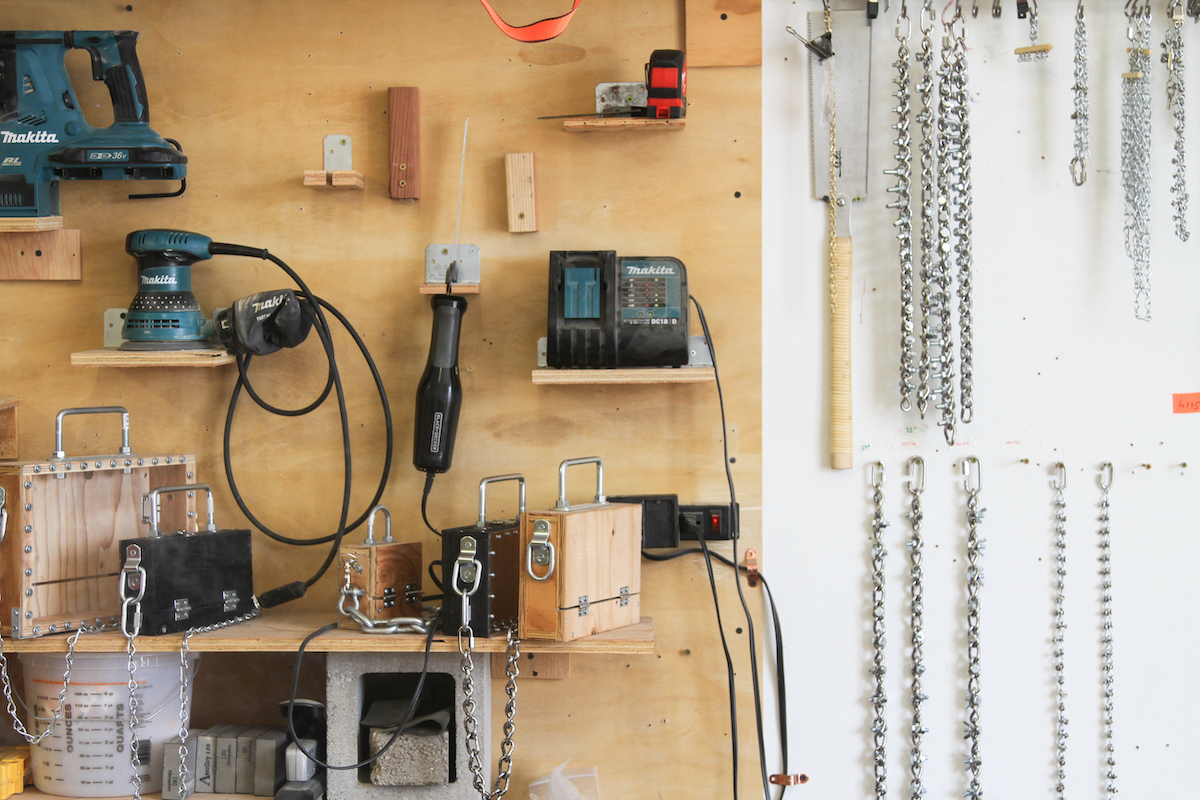

SD– That's a symptom of obsession for me. When I find something that feels really good, I do it alot – like pizza. When I drill a screw 1000 times, the act of labor becomes a sort of ritual that turns into meditation.

AM– That sense of repetition gives you the support or structure that you're looking for to figure yourself out along with the piece. It's like completing a rosary, the repetition with the beads creates faith in something.

SD– A certain amount of screwing and bolting creates a sort of religion around the work. Construction is a primitive act. For me I’m trying to return to the hand and mind and soul relationship through the act of labor.

AM– What do you think repetition does for you? It seems like you aestheticize repetition? That's something that's really interesting to me about your work. You're compounding on the baseline of what an object needs. What are some of your influences in that way?

SD– Construction sites are where I mostly find influence.

I also think repetition, at least to the degree that I do it, starts to prove a point. To repeat an act, even a very simple act like screwing a nail, when done 1000 times, gets challenging mentally. Repetition in my pieces helps me understand my limits mentally, physically, and spiritually.

AM– I think the essence of your work very much implies the body, there’s this use factor – where the body comes in or is activated. Aside from preparing and imagining any of the pieces, you’re also involved with screwing all these pieces together, locking all the locks, etc. I find it a subversive way of pushing the figure into the design.

SD– When I was younger I spent some time with Larry Bell who told me that he never made a piece that he couldn’t build alone – meaning that one single piece of material could never be too large for him to carry alone and one single piece could never be too ambitious for him to build.

My work follows a version of this. My body, my ability, my stamina determines the scale and the detail of the work. If I can’t screw in 1000 screws, then the piece won't get done. I have to be ready and willing and capable of constructing each piece I imagine. So my work, right now, represents the strength of my body.

AM– That’s a nice way to think because you’re more brutalist in a sense of the way you are working with your hands, which is what I’m much more interested in nowadays.

There’s been a movement towards handmade and handicraft, but what’s really subversive and interesting about your work, and what drew me in initially, is that I found it polarizing. I didn’t quite know where to place it. Your work actually requires a lot of the hand because so much of it requires these manual movements.

SD– My work wants to be touched, and I think if something is going to be touched, I want an act of reflection to go along with it. For example, some of my pieces appear uninviting to a sitter, but inviting enough to be curious. This betweenness might make someone hesitate and consider sitting in a way that they haven’t before.

AM– You basically insert an intention and you become aware of the intention by doing the most basic form of action, like opening a cabinet, but once that position is repeated, that’s when things get a little strange, and kind of exciting.

SD– I just want the user to get the same feeling in opening that cabinet that I had while constructing it. It is my way of sharing my ritual.