Inside Jester Bulnes’ Outrospective Visual Diary

So, tell me about DENTRO.

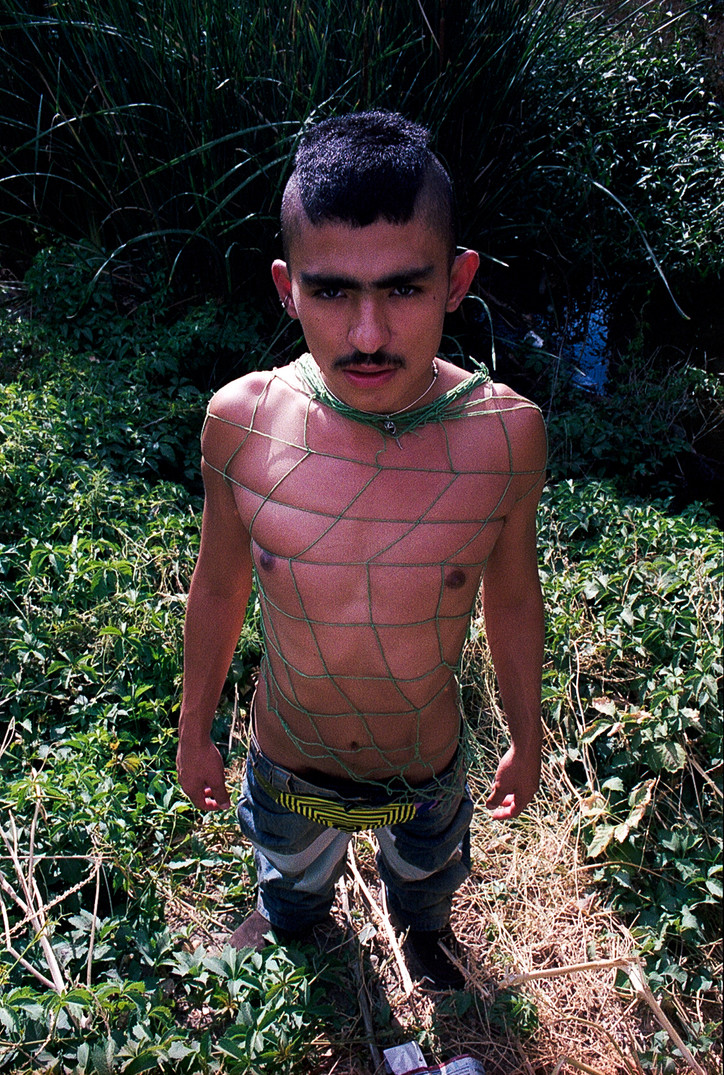

DENTRO is a visual diary and my debut book. It encompasses a large multitude of imagery. I spent most of this past year curating and creating imagery for the project. But I also consider it a peek into my archive over the last three or four years. I pulled from what I felt fit into the theme of DENTRO, which translates to ‘within.’

When I turned 18, I made a smaller zine project investigating my queer identity — I had just come out around that time. I had been closeted for 18 years, so it was very much an introduction to myself in this new way. DENTRO is post-coming out, a period in my life where I’ve been able to explore more of that queerness. Then there’s also my Latinidad. I have a Mexican mom, and my dad is Salvadoran — he was an immigrant. I thought a lot about their experience and what that means for me as a Latin American. I think a lot of people can relate to that diaspora and that sort of in-between stage. I'm really interested in what comes after that. How do we push past that and move forward instead of just getting stuck in that space?

In-between is interesting because it could mean stuck, but it could also mean finding ground in multiple places. Were both of your parents first-gen immigrants?

No, my mom was born here, but my dad wasn't. However, my mom's experience is kind of unique too. Our grandma low-key lies about where she comes from. There’s no concrete answer. My grandma grew up in Watts, California, during a time when it was very anti-Black and anti-Latin. My grandma tried to assimilate to whiteness, and as a result, became anti-Black and anti-Latin. A lot of the people in my family on my mom's side are very whitewashed. My mom has six other siblings who share the same dad, but my mom’s father was Mexican, so she was always apart. With how I grew up, I didn't know much about that. She didn't have a good relationship with her dad, so part of our history was pretty much lost.

My parents divorced when I was in third grade, and then there was alcoholism and other problems between them. My mom didn’t even allow my dad to teach us Spanish. That experience was confusing to decipher, especially growing up in LA. I grew up in Downey, which is somewhat more suburban and south of downtown. The neighborhood was predominantly Latin, even thinking about the kids I went to school with. I was also maybe lighter-skinned than them and didn’t speak Spanish. The other kids would say, 'we're more Mexican than you,' because of that. It really skewed how I felt about my position in the world.

How did growing up in LA inform your perspective of the city now, especially when you're working on a project like this, in which you're purposely documenting queer brown people?

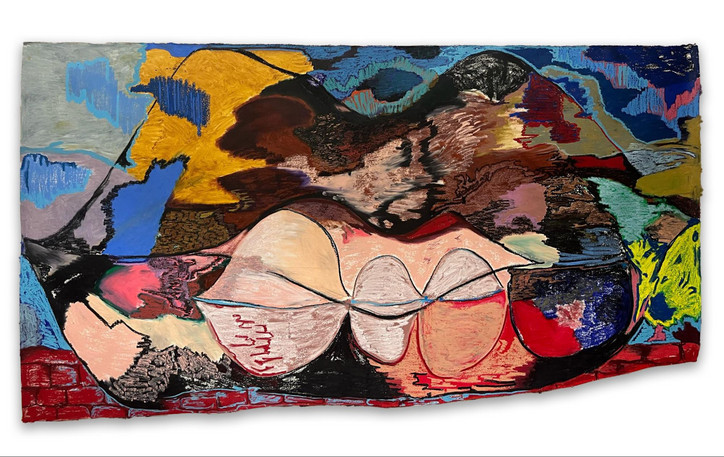

It was interesting because of the history of Latin people in LA, which was something that I wanted to take into consideration. That's why it's important for me to highlight these people in these spaces, but also because I come from more of a suburban part of the city. That in itself creates a unique relationship with LA because the city was always a 15 to 20-minute drive away. When people hear LA, Hollywood comes to mind as well as a certain exclusivity attached to the city. I wanted to challenge and play around with that. I feel like all the imagery and photos I take allude to LA but may also look like they're not even in the city. I often shoot around the outskirts. I'm very drawn to more urban spaces — the graffiti, the tagging on walls, the textures, the concrete.

I can see that. Location definitely comes across as ambiguous in the images, but there’s also a sensibility that translates as very LA. Were they all taken there?

90% were. There's like 10% that comes from one trip to Mexico City and a couple from a more recent trip down to TJ — only two.

How much planning went into every image? Some carry a candidness as if taken unexpectedly. Others feel more intentional.

Since some of the images were taken in a past before DENTRO, and others taken on trips, some are literally candid. I wasn’t thinking about this particular theme. Sometimes I feel weird about having a camera with me and constantly shooting. I would love to be able to be that kind of photographer but it can feel a little corny. I don't know that I've ever really gotten past that. When I went to Mexico City, I wanted to document that time and have a record of it, so that was purposeful. The other imagery is a bit more planned.

I style all of my shoots, so everything is more of a larger investigation and very detail-oriented. It starts with thinking about a person I'm interested in capturing, then the outfit, or vice versa. Again, thinking about the outskirts of LA, there are some locations I'll revisit, reorient and reuse. When I'm shooting, all of it comes together. The actual process is pretty spontaneous. It feels very intuitive. It's almost like a dance between myself and the model. I always want them to feel comfortable and to make them look and feel their best.

Are all the clothes you use from your own archive?

I will admit, I do have a bit of a shopping problem. I’m a fashion lover, so it just makes the most sense. That's where it gets a bit tricky because when I'm out shopping, I want the clothes for me, but I'm also thinking: is this a garment that I could possibly shoot with? That’s also where this idea of self-portraiture comes into play a bit because these outfits are very much how I dress. There is showing them as a subject while also showing myself.

Is that why you also include selfies in the book — to further stress that there's no separation between you and them?

Yeah, exactly. There’s a fluidity that I think is important.

Do you choose subjects based on shared identities, or do those reveal themselves during the process?

I’m definitely purposely casting people based on whether we share similar identities, whether queerness or Latinidad. I do try to stem away from photographing white people. No shade; it’s just not what I’m trying to highlight. But I’m also obviously trying to focus on uplifting trans people as well, especially now that I’m more confident in identifying as non-binary, and with meeting more friends, I am exploring what it means to be trans femme. There’s always that aspect of capturing those bodies and faces that most resemble my own.

Are all the subjects friends of yours, people you know personally?

There’s a fine line. I basically grew up on the internet. I’ve had Instagram since I was 12, 13. I used it almost like a transit system where I could connect with people. Of course, everyone does that online now, but for me, it was an important way to connect with others and explore my queerness while maneuvering the closet. Some of the people I photograph are what I would refer to as mutuals — we follow each other and know each other digitally and then turn that into something more IRL. When we shoot, it's the first time we're meeting or we've seen each other out and about. It’s important that I’m highlighting and documenting people within the same circle, community, and subculture where I find myself in. Then there are the few instances where I'm casting someone I don't know purely because I think we share an identity — or that I simply find them beautiful.

You call the internet a transit system, like a liminal space. Do you think this project would translate properly onto social media from its physical form?

That gets tricky because the whole purpose of this project was somewhat an antithesis of the internet. The internet is such a weird place, and I could talk about it for literally hours. Yes, I was raised on the internet, and it does a lot of good, but now we live in a completely different digital age than what I knew. This project really needs to exist in this physical manifestation. Again, no shade to other photographers, but I don’t always feel like I have to post all of my work on the internet. Photo is very much a fine art practice, and unfortunately, it's not always seen that way. It’s important for me that it is. Seeing an image in print evokes a different feeling and promotes a specific kind of experience.

The internet, as it is now, has normalized the constant production of images, especially when it comes to photography. A question that people don’t seem to think about people don't think about is it's like, 'Yeah, are we making this work for Instagram, or are we making this work for the sake of making the work?' It’s not that one is better than the other, but it comes down to the art and the artist — how they want it to exist in the world. For my work, I think it's going to be a little bit difficult for me personally to translate the work to social media because I don't want to. It makes me wonder if I’m missing opportunities by not showcasing what I’m doing, but that wasn't the goal to begin with. It’s kind of just like if you see it, you see it, and if you don't, it’s just how it is.

How does this project subvert the notion of a traditional photography book?

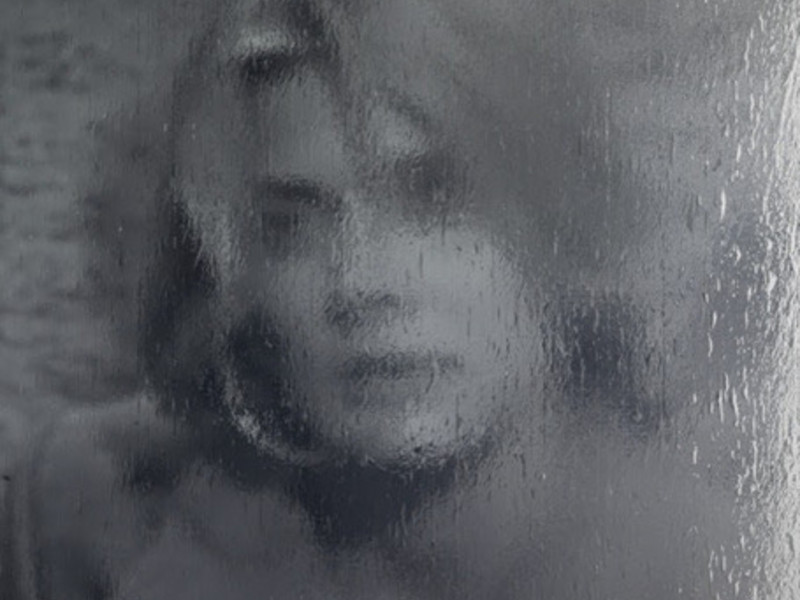

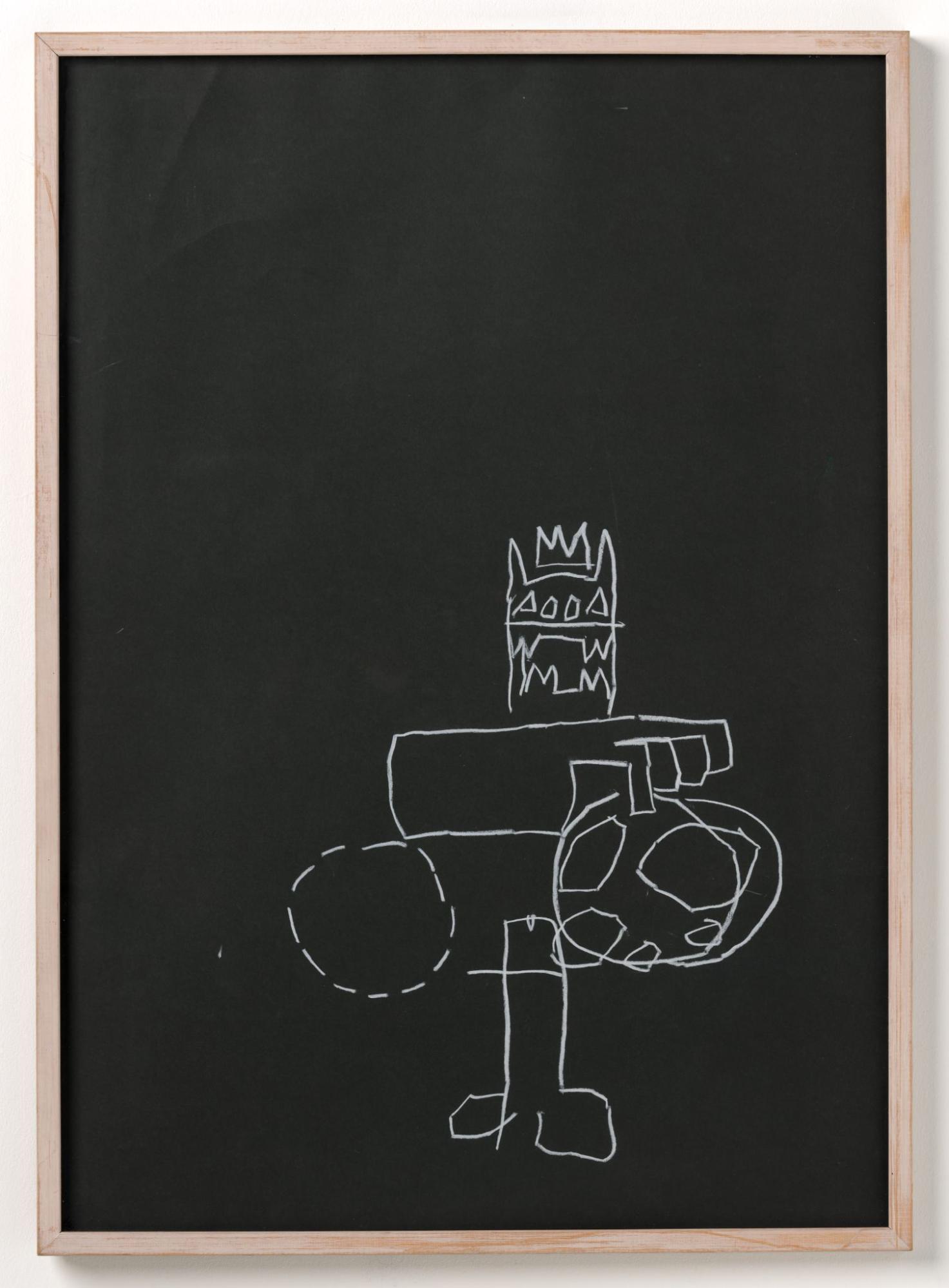

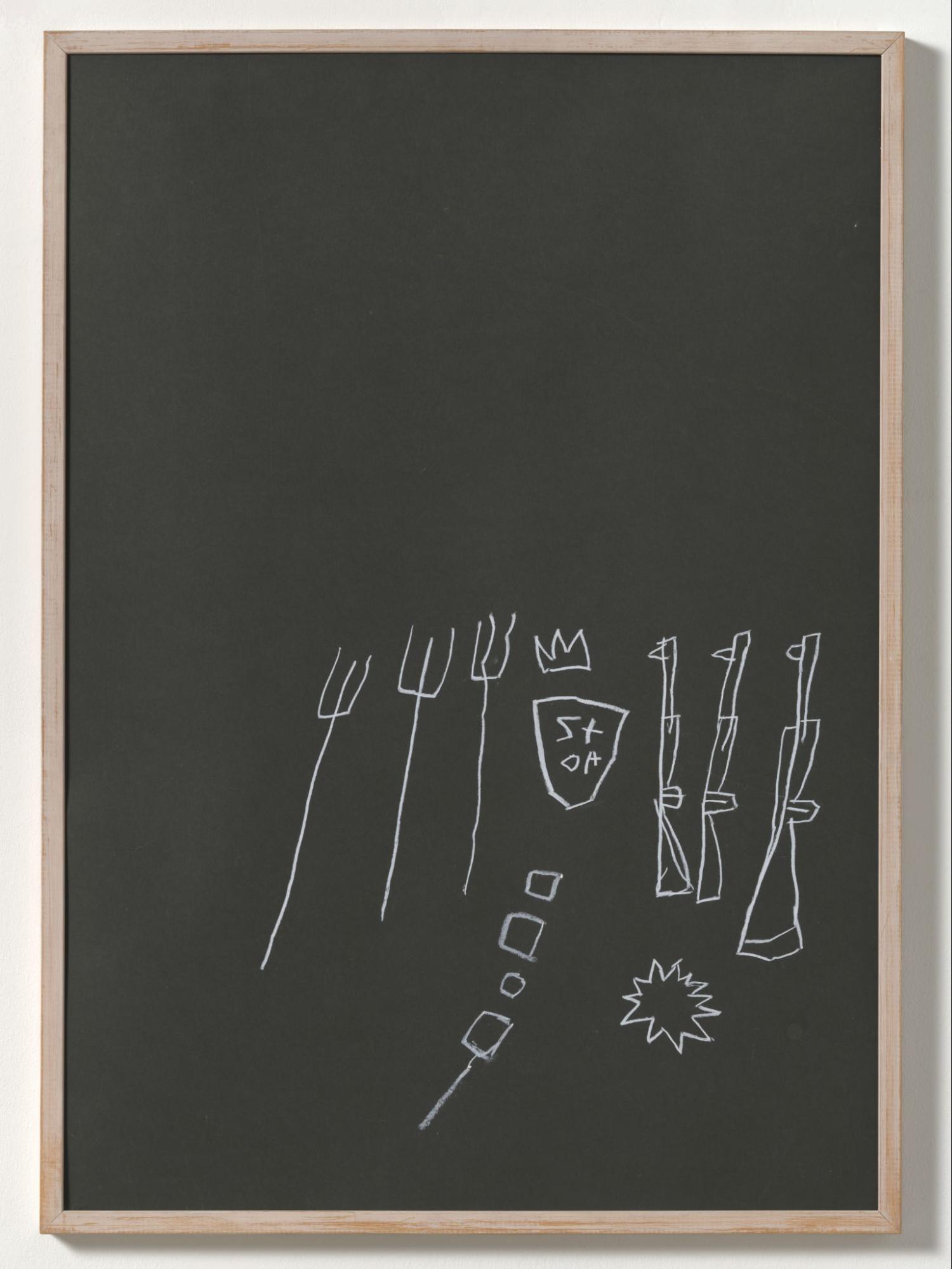

It's hard to say because when I think of a traditional 'photography book,' I see it as streamlined imagery. I really wanted this project and this book, in particular, to be more of a personal diary vibe. I also view it more as an object. It functions more like this sort of larger collective instead of just being a straightforward book of photos. It’s also because there are iPhone photos, video stills, some ceramics, and a sculpture of mine because I wanted to challenge visual imagery and what that means.

There’s also that aspect of challenging normative media by focusing on queer bodies. Do you feel like there’s anyone that won't get it?

Yeah. It's not that they won't get it, but it's definitely going to be overlooked. The work speaks from personal experience, not one that everyone will understand, and that’s okay. There’s still a way for people who exist outside of the identities I focus on to interact with the work. That’s interesting to me too.

Why Palm Grove Social?

That's where it gets tricky to be completely transparent. It's one of these things where it's like, I've created and started this project literally after I turned 18. I was like, 'Okay, next project, it's giving a book. By the time you turn 21, it needs to be out.' I first intended to release it all by myself, but then I started reaching out to different venues, galleries, and bookstores. I'm familiar with Palm Grove Social because it is run by Cast Partner, who I’ve worked with before. I sent them an email on a whim and they were very quick to respond and were pretty familiar with my work. I was like, 'Oh wait, this is kind of gaggy, not them already knowing about me.' Then we set up a meeting for that coming week, and I felt comfortable having this work exist in their space. They're trying to create this community space and cultivate this network of cool people. They're very trusting of me and have allowed me to transform the space. I want it to reflect both me and the book, a sort of infusion.

Kind of like a liminal space.

Exactly.

Do you feel like there's going to be a huge turnout with the community you've built around you in LA? Are the girlies excited?

The girlies are definitely excited, and I don't want to toot my own horn, but I do hope and trust that it's giving a big turnout. For sure, everyone who's part of the project is so excited. This is a long time coming, and I feel like I've teased it online dozens of dozens of times. Both subtly and more overtly. In the past couple of years, I've made a name for myself in the community, and I really want to continue to do that and not only for me but for the bigger picture. I want it to show that if you want to do something, you really just have to do it. Thankfully, I do feel very fortunate and blessed that opportunities have coincided with it.

Tell me about the ‘Yasssters.’ You've kind of created this niche and inclusive online community around you and the exploration of your identity. I love to see it.

The Yasssters are giving. All the lit b*tches, essentially. I love to just be like, 'Are you a Yassster?' That's one of the deciding factors and the automatic yes, it's like, period. No? I'm kind of like, you're throwing me off. It should always be yes.

Okay yeah, I’m a 'Yassster' for sure.

Period. It does stem from this more femme identity I’m exploring, often when I pop out, but I never want it to feel costume-y. The gay boy to non-binary trans femme pipeline is real. I commend all the girlies and men who are transitioning, especially in today's day and age, with everything going on. I’m still tiptoeing into that area 'cause I just don't know that I am ready yet, especially how I was raised and all, but it is part of me. The 'Yasssters' started out as a bit humorous, but it has grown into something very real. It’s this way for us to maneuver the world, get out there, and get closer to feeling comfortable. Weirdly, the 'Yassssters' get it and are doing it.