A Prism of Your Own Reflection

The two-sided set has collected symbols of perfection through two different artistic journeys. Campos's vision board is derived through the roots of dance music and kinetic sculptures that blend tracks into one loopy rollercoaster ride of an auditory experience. Once the play button is pressed, the listener is taken through the wind of smooth and sleek beats, arpeggios that scream personality, and unforgettable rhythms which recognize futuristic elements that run shivers down amused backs. City Planning is a reference point for infinite, and Campos sets out to make music that builds on forever, like ellipses at the end of a trailing sentence.

In Die Cuts, Maker's side begins somewhere in L.A., where dreams turned into realities and songs were recorded with a be-all-end-all list of artists like James Blake, Jay-Z, ASAP Rocky, and more. The assemblage of objects is parallel to Maker's bug-eyed view of music making. Materials of samples and sounds dissolved into artistic collaborations and, then further vocal methodologies brought on new incites and musical experiences. Reflecting on L.A.'s Koreatown, Maker concluded how he wanted to come up with something from his point of view. Die Cuts worked as a butterfly project allowing him to break free of his shell.

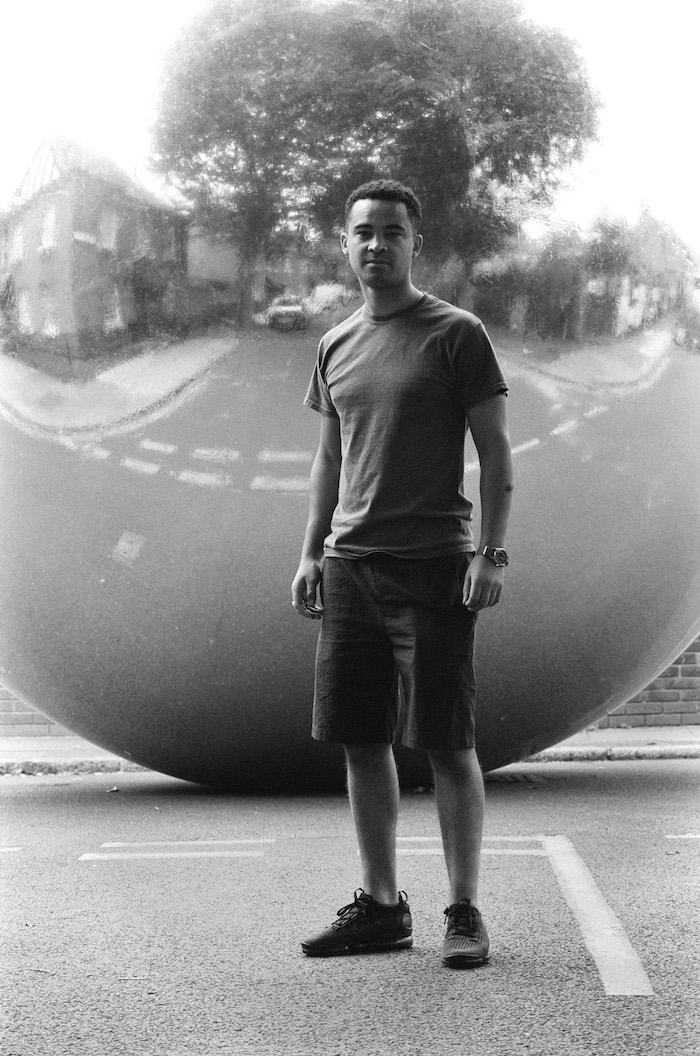

Die Cuts and City Planning are two sides of the same experimentalist coin. A project thats coming just in time to listeners as a portfolio of work to expand their minds. The evolution of Tom Shannon, a grandmaster in the art wold was only another layer of the immaculate project. Throughout Shannon's career, he's sharpened his tools and explored all that art can be. From paintings to sculptures and high-end achievements across new inventions— he exemplifies how great art expands with time. He doesn't shy away from changing patterns— he moves with the currents, letting himself become inspired by the life around him. This only makes his finalized pieces so much more engaging as it holds a reflection to the viewer proposing the question of, "well, what do you see?" The cover art for City Planning was created by Shannon as a momentum to the ever-evolving music of the project. The two artists collided to polish work narrated in building worlds within worlds of art.

In an interview for office, Shannon and Campo sat down— a first for the both of them, as they've never seen each other's faces— to talk about the music, the art, and the future.

So, what's new in your life? What's a random thing that's made your day?

Tom — Well, I suppose the good news is that our recent installation in Menorca looks very nice, beautiful setting. And so, I think, that's what cheers me up.

Kai — I'm in a pretty boring stage of making a record right now. So, I'm in this room without any windows for most of the day. So, my highlight of the day is, is really the chance to speak to Tom, as it actually is the first time we're getting to speak. We obviously corresponded a lot on like through the project, but not on camera or anything.

It must interesting to see each other's faces, and just talk to each other regularly. Now that you've mentioned the collaboration, what went into the process of making the artwork for City Planning?

T — Well, I think it has a lot to do with Frank Lebon. You know, we had met and he had a good idea of doing something together. And I was very delighted to be able to have an opportunity to do something like this. I love the music.

What was the vision board for? Especially since the cover is done in black and white.

T — Well, we had many different ideas of doing it with sculptures of different types of balancing and magnetic sculptures, so there was probably 100 different ideas. But eventually, it became clear to do something practical for a short period, and they had this idea of using four balloons that were packed together and create a little hut that could be photographed, that had unusual optical abilities, where all the balloons touch each other, there's a kind of infinity reflection between which gives it a very interesting look and appearance.

Are you guys both equally inspired by technology and the futuristic concepts?

K — Making lots of work really is about trying to make sense of different thoughts and feelings that you have going on at any particular time and trying to condense those into a artwork. I think that's why it's often difficult to explain what it is until you know that it's right. And because it kind of is able to illustrate maybe like a certain contradiction, or a feeling, or a fear or whatever ,just fills a space that that you're aware of. And so each time that I make a record it's, you know, coming from quite a different place. There's certain themes that come up. And this is the first time that this is, you know, certainly a record that was slightly more conceptual, as it's been different from my usual approach in the last 10 years previous. So, I had more kind of literal ideas that I wanted to try and cover in the making of the music. And some of that is also in reference to other music. And there's a debt that's owed to the music of Detroit in the late 90s and early 2000s, which often was very interested in possible futures. And, in my mind, anyway, it was a forward looking music that was interested in the aesthetics of the future. And yeah, so when I was talking about some of these ideas with Frank, he, he pulled Tom's book down off the shelf, and I couldn't believe from the first page that I turned just how how much it resonated with me. And then every page after that was, it was a very exciting moment, actually. And, yeah, I was overjoyed that we're able to kind of pursue it together. Yeah.

That brings me to my next point, it was brought to me that after 2017, you went into this like venture of listening to different types of dance music. Who were the musicians and artists in your rotation?

K — So, there's probably a lot of kind of American artists, particularly from the beginning— like early 2000s, that were not necessarily the beginning of this movement, but like, to me, the most interesting part of that is they're kind of around the world like Jeff Mills. And then as you get a bit further on in time, there is like Terrence Dixon. And then in the UK, there are people like Regis, Basic Channel, Shinichi Atobe. They were all kind of operating in a sonic world that I was definitely taking a lot of influence from, and then someone more contemporary artists as well, as it was an influence on my work.

How did kinetic sculpture sculptures like blend into this Embarkment of listening to these just like worldwide musicians?

K — There's been a few kinds of pieces of visual art that I was thinking about when I was formulating the start of the record, but the kind of takeaway from all of it was just an attempt to try and represent texture in sound that I hadn't really thought about before. And so I want it to have the same feeling that I had— not necessarily about a particular sculpture, but the sense of being in a room with a sculpture. One of the problems with sound and with music it has a kind of a duration, where you you sit down, and it has a start and a middle and end. And what I was thinking about after in relation to the sculpture work was that I really enjoyed the fact [about the sculpture] is that it's kind of forever. When you experience it, you walk into a room, and it is there. And, you know, you can look at it from different angles, and maybe there's a kind of your relationship with it that changes over time. But I was really interested in capturing the kind of different textures I'd seen. Also, this experience of complete wholeness in being enveloped is something as opposed to experiencing predictability. Like narrative form.

It sounds as if you were trying to contrast a 2D perspective of music and turn it into something more.

K — I kind of wanted the record to feel at times that it was just kind of running in the background forever, and that you were having to just experience it for that period that you were listening, but it would still be going on after.

The idea of infinity is really cool, I think that expands music, because it becomes something that you can press play or pause on, but something that has its own world beyond just the listener. Is this something that you resonate with, Tom?

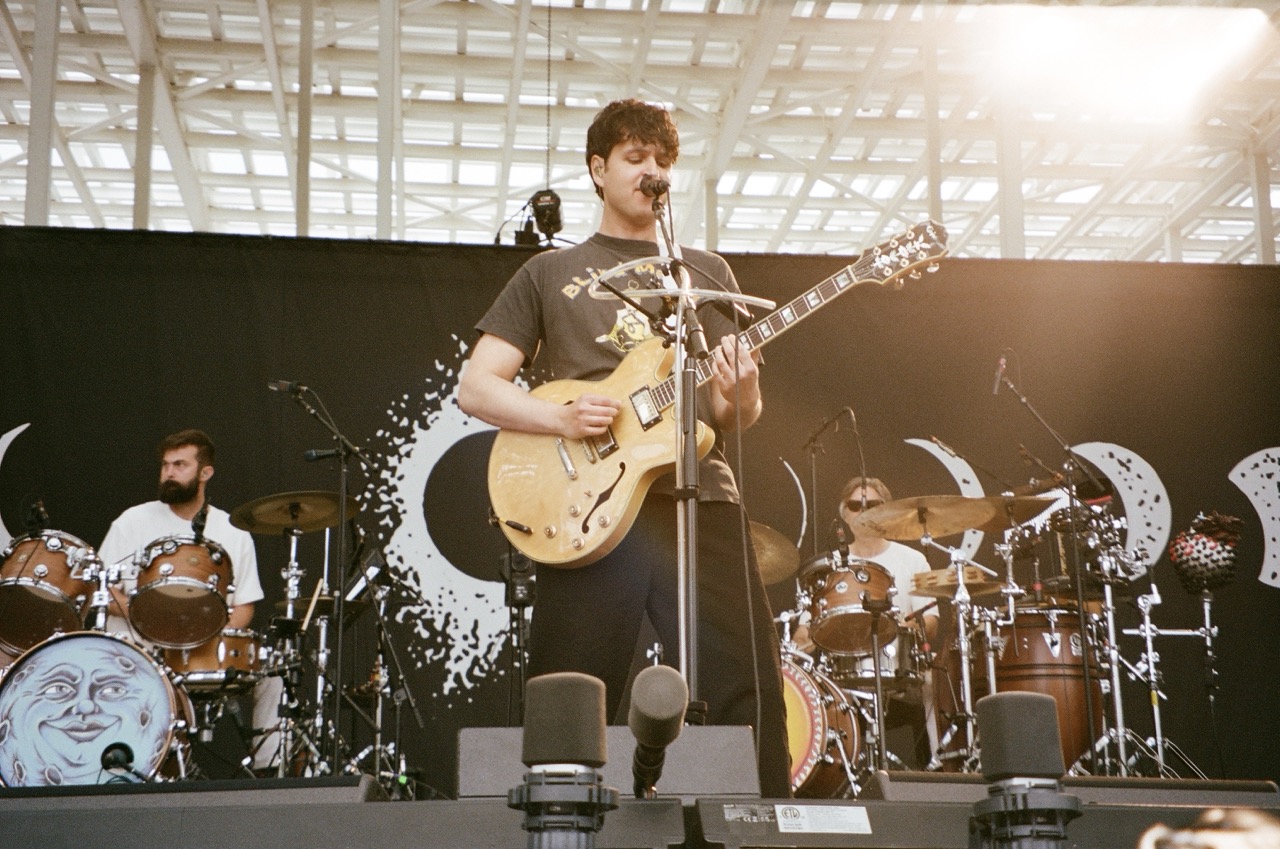

T — Yeah, in a sense, it's very solitary work. You're in the studio, you're working without time really. The musician, of course, is mastering time, and performing at the moment, and experiencing the feedback of the reaction to it. And it's so that the actual performance part that equates to work you're doing physically in a studio, but what the musician is doing on stage, it's, it's so different. There are overlaps in visual rhythms and I think a sense of newness that's possible to create, however ambiguous, something possible.

What is your process when you're creating art? How do you immerse yourself before you begin in your work?

T — Every day I draw on the same size paper— business paper, and then a flow of ideas happen. And then one thing leads to another. You do one drawing, and then you look at it, and you respond to what you've just done. And then you do another drawing, and then that leads to another thought. So you build up micro impressions of the first ideas, and then you start connecting it to things that you've done before. This tends to add up, it's sort of a accumulation of thoughts that go into the new work. And, you know, you're always trying to improve on things or make inventions of some sort.