A Reflection of Things

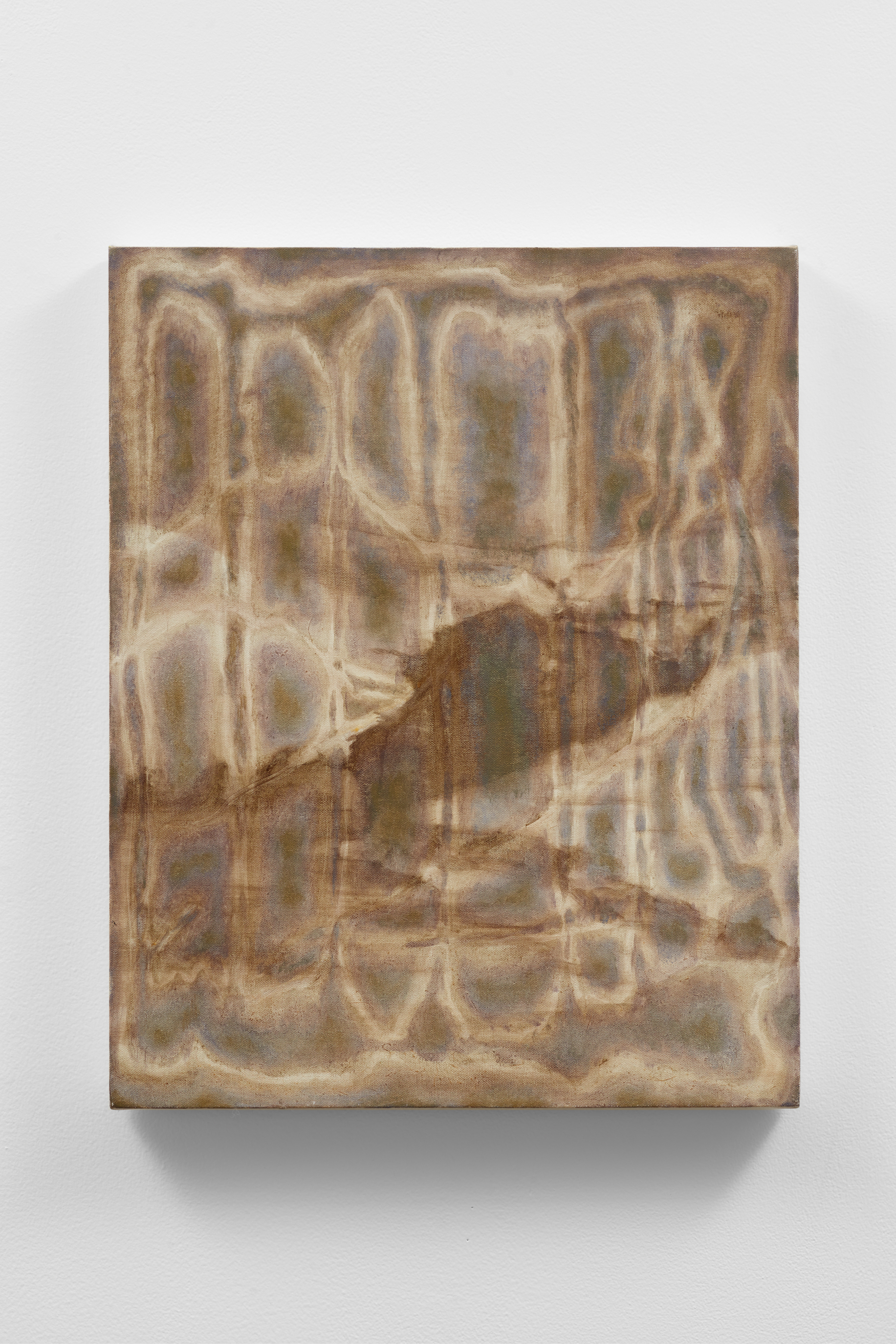

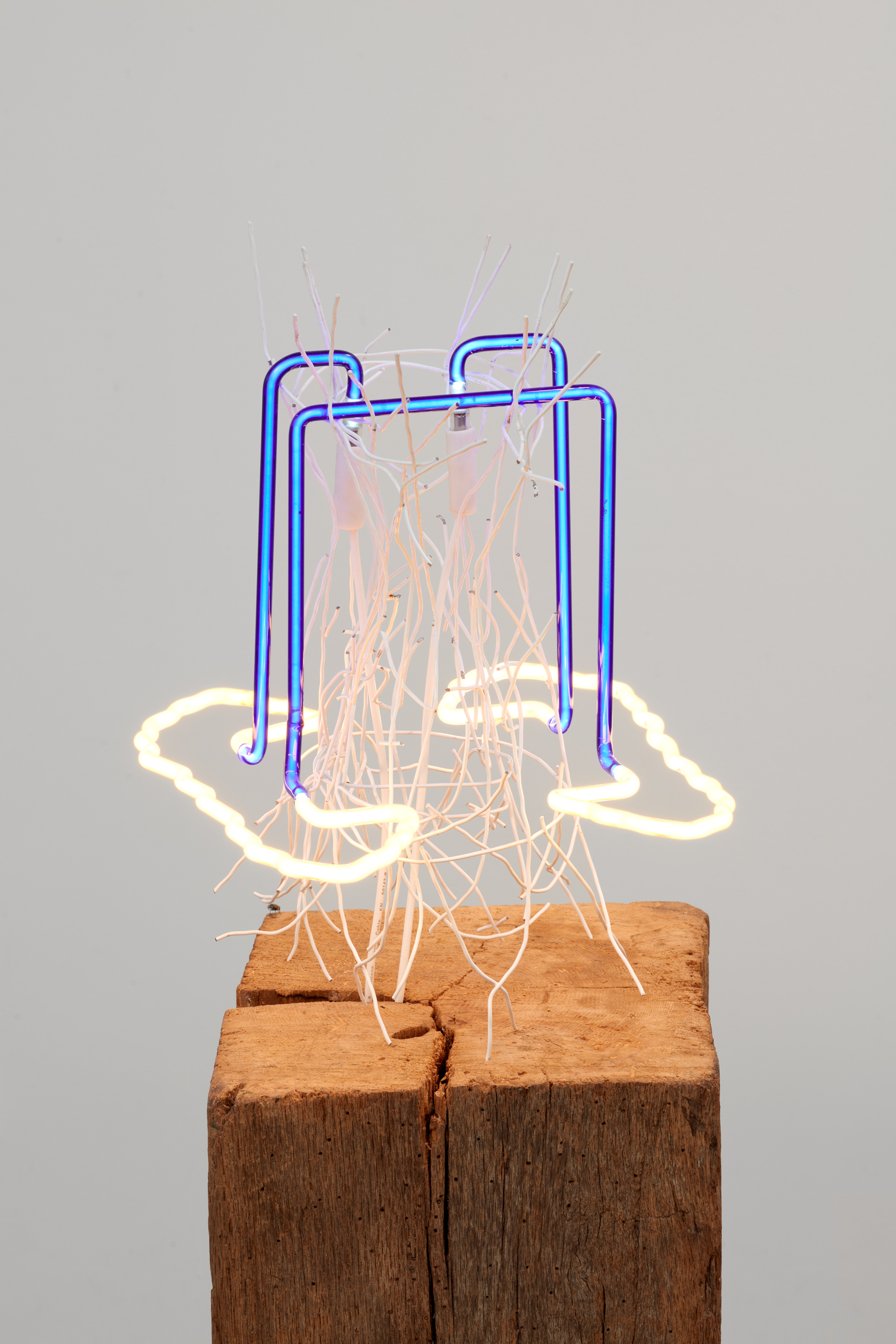

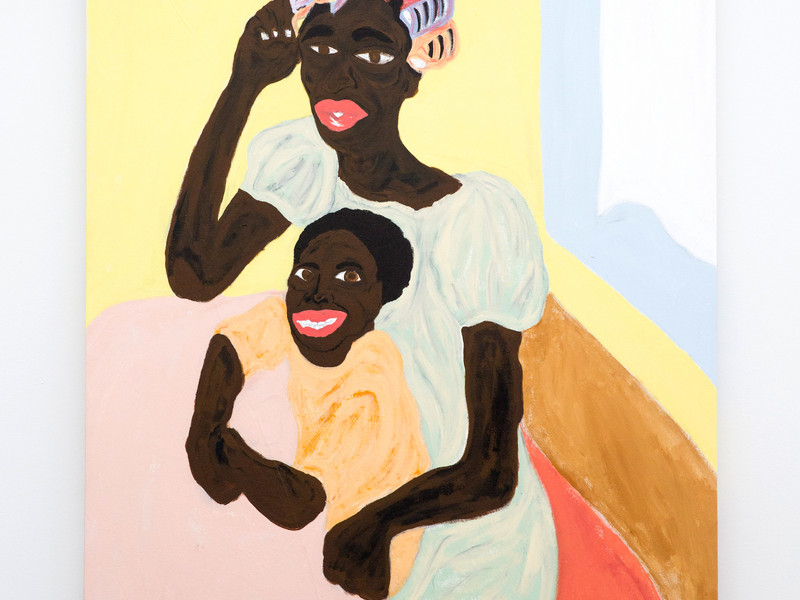

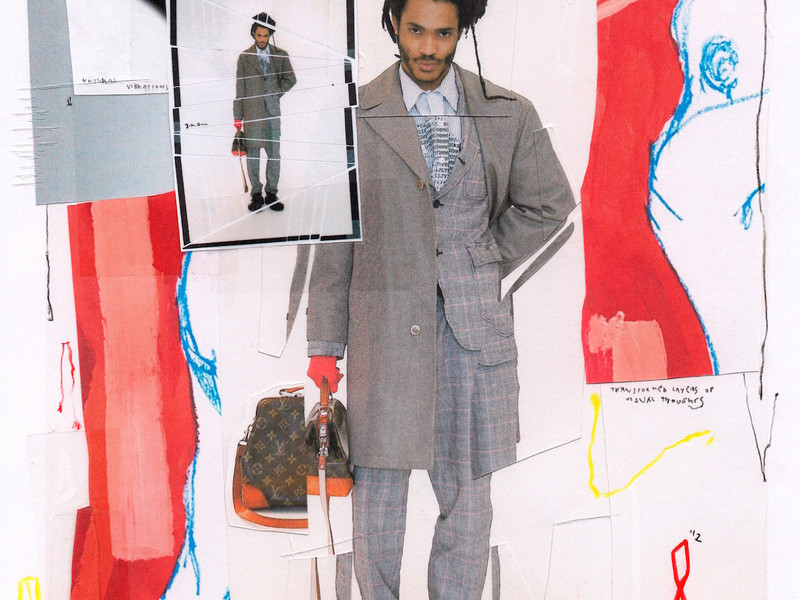

The artist walked me through his show, shedding light on the themes that pervade his work and personal history. On one wall of the gallery, a multi-part film is projected. The others are hung with sculptural media works—honeycomb-like wall fragments printed with partially legible words, draped fabric and layered panels laser-cut with phrases, figures and comic book scenes. An enormous gilded sweet potato sits quizzically in the center of the room. The work is not obvious, nor is it obscure. It challenges us to pause and question the ways in which we interact with the people and phenomena that influence us.

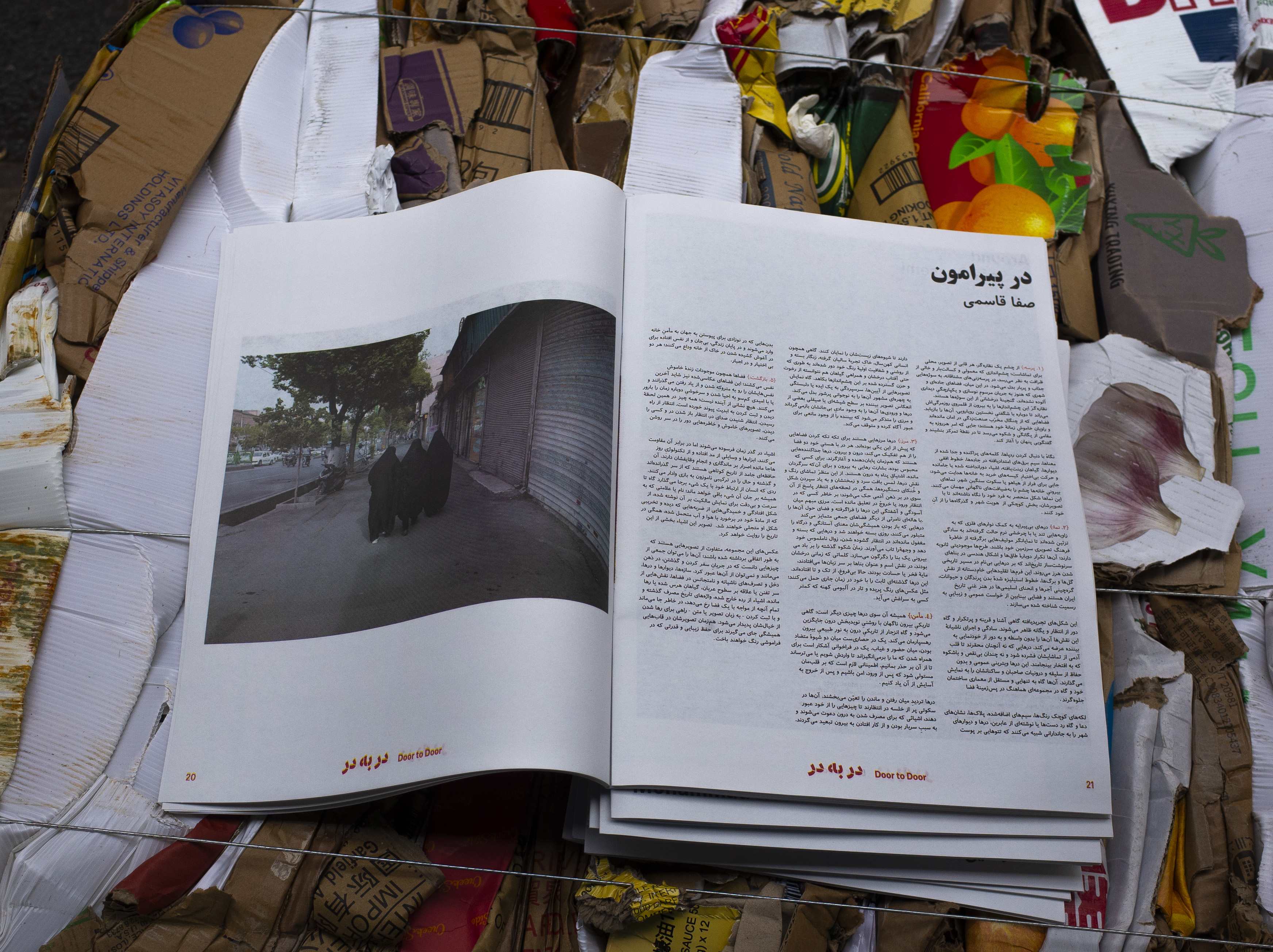

IA: Let’s begin with the film, I think the film is somehow the heartbeat of the show. Actually, it’s the rhythm of the show, because it goes on and off, and makes the exhibition breathe, a little bit. There are seven different sequences. This film is about these two places that are exactly at the opposite in the world. This town in Indonesia named Palembang, and this other one in Colombia named Neiva. They’re both small cities, not well known, not big economies. I wanted to go to these anitpodes to prove many things. I wanted to make this an historical parallel, and show how different these two towns are, but show mainly how close they are, despite the fact that they are exactly the farthest place they could be, one from the other. So the film talks in a way about geopolitics, and also about the idea of the other. How we construct the idea of the other as different, like our neighbor, or the people in the next country, but we’re pretty much the same. Not only in terms of sensibility, but in terms of economy, in terms of history. Like, Indonesia and Colombia, they were both colonies. One a Dutch colony, one a Spanish colony, and they have pretty much the same history, with of course several different details.

O: So why is the film split into seven parts?

It’s chapters, and so the film is 21 minutes, but I just wanted people to interact, I didn’t want to make people sit and watch for 20 minutes. I didn’t want to have the cinematic experience, but more like, somehow you’re watching this, and almost like a dream the images appear.

Do you think it’s best that people see the film in its entirety?

I think it’s OK if they get pieces, each clip has its own independence. Some are more like music clips, others are text, some are sound and images.

The viewer in a gallery or museum can ask a lot of a video piece, there’s often an attitude of, “I’ll stay here if it grabs me.”

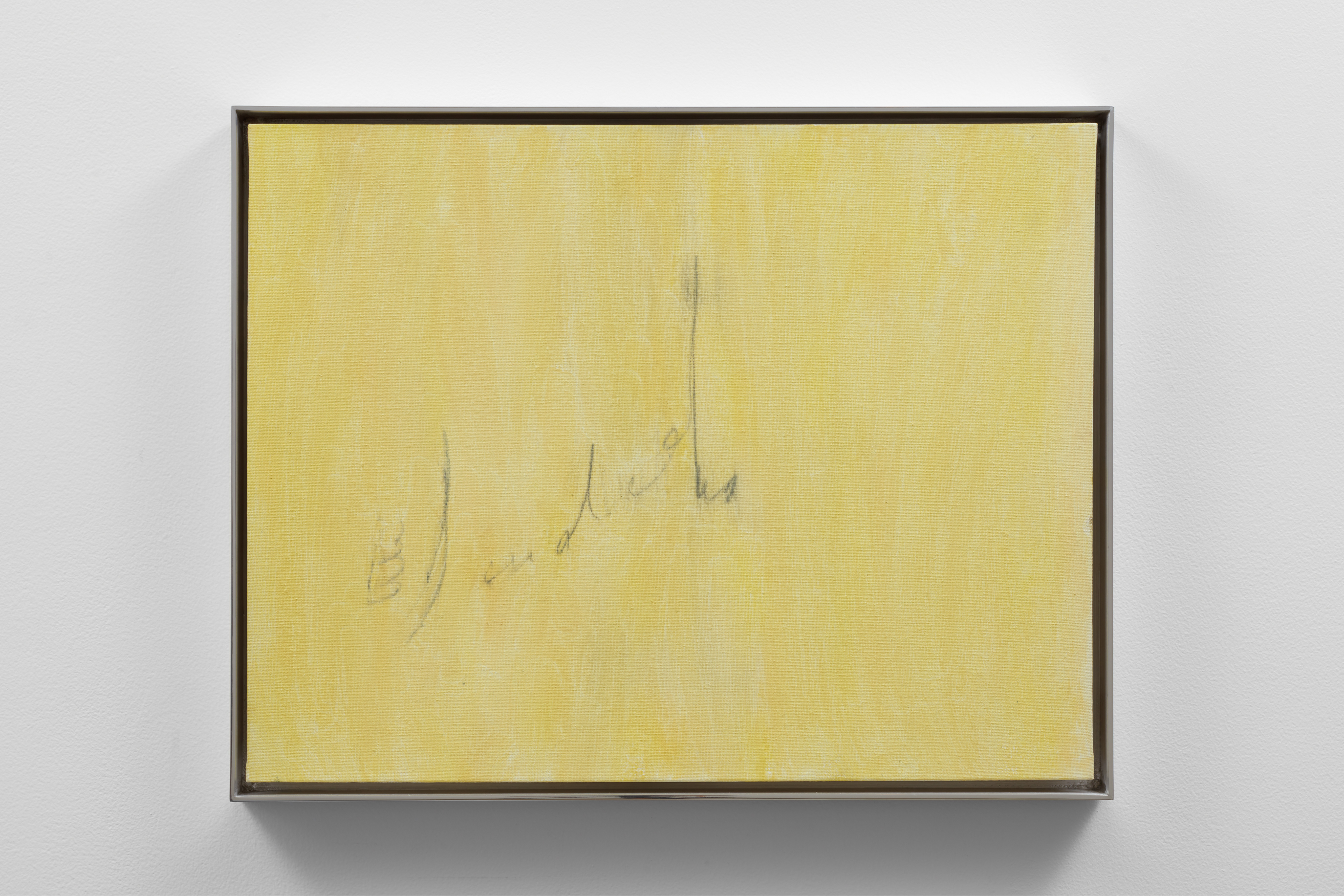

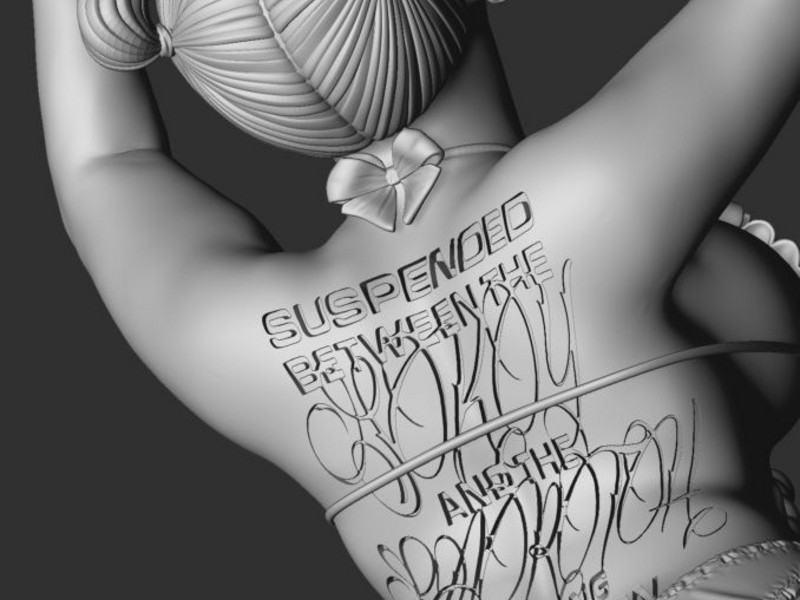

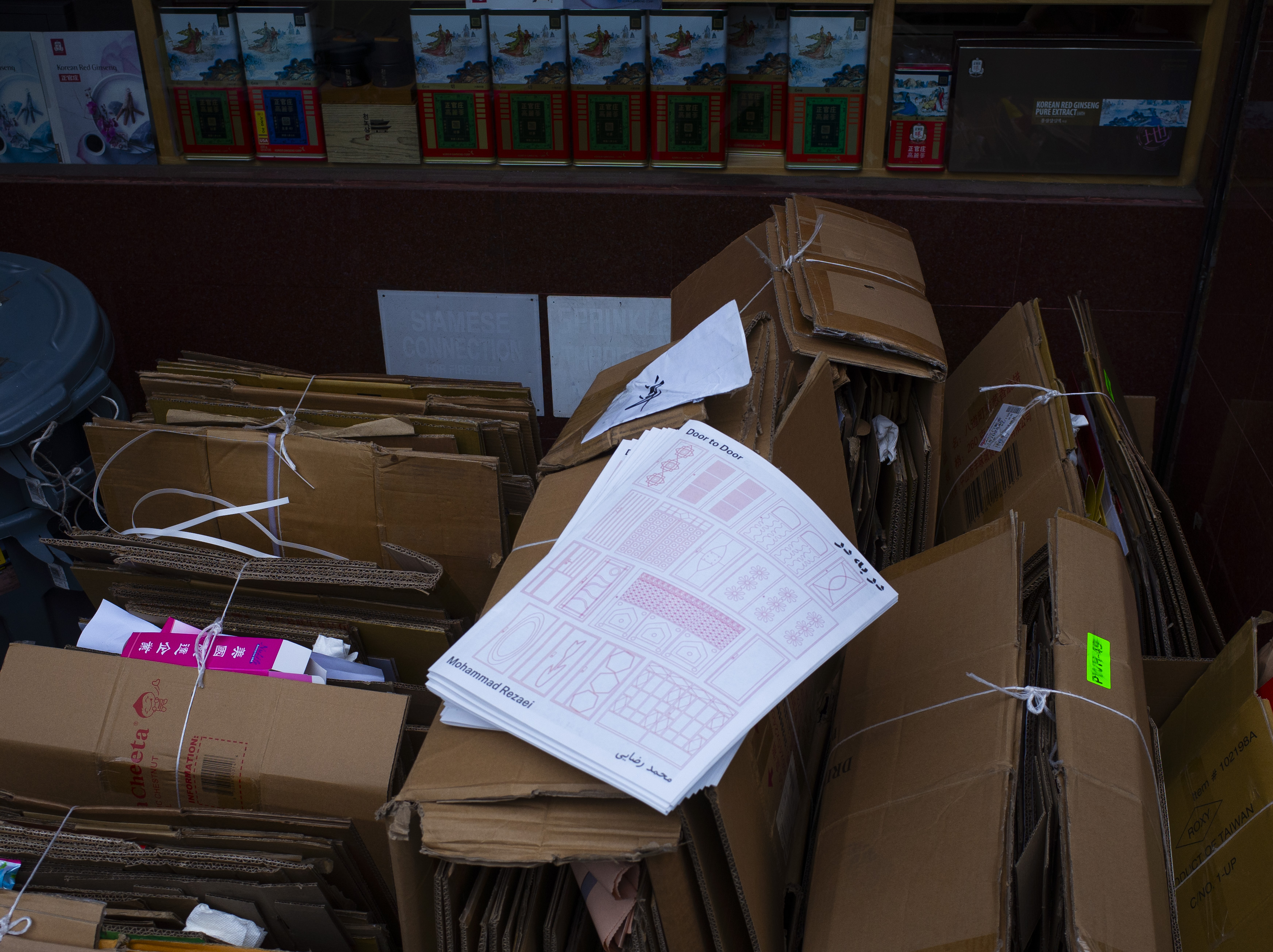

You need to be very engaging, yeah. It’s very horrible when you arrive to the exhibition and it’s the credits, it’s like “Ugh.” And they’re long. So that’s kind of the heart of the show, in a way, the pulse of the exhibition. Then there are paper works. I’m always collecting material, actually I started because I found this story about the company Kodak. Somebody who worked at Kodak told me that in the ‘40s, the company switched the developing process from Kodachrome to Ektachrome, because they realized when the pictures get old, they turn red. It was during the Red Scare time, so they said the photos cannot be red, because red is the color of Communism. Ektachrome, actually, when the images become old they become bluish. So I made this project reddish blue, and tried to find if the story is true or not. I actually never found the answer, but I found a lot of history on propaganda, or industry colluding or interacting with ideology. And then I expanded to like, history books, how history is taught in schools. For example, the images in some of the collages in the show come from this comic named Is This Tomorrow?, which is a comic made in ’46, the same time of that Kodak story, and the name is Is This Tomorrow?: America Under Communism, so it’s a fictional comic, advertised to children and teenagers to make them afraid of Communism. But it actually touches very large themes about unions, about racial stuff. It’s very hardcore. They say, for example, “Of course, Communists will try to empathize with minorities. What they’re going to do, is they’re going to start making minority conflicts. So they’ll show the ruling party saying super racist stuff, and then some insider will say ‘You see? They’re so racist here, you should join us.’” Same way with Jewish, with African American. So it’s very hardcore, it’s very twisted. And at the end of the comic the Communist party is in power, and you see the White House with a Communist flag.

Perfect propaganda.

Yeah, and it’s weird because the rhetoric is pretty much the same as what we’re hearing today. So I Iike this title, Is This Tomorrow? And I use these images, but then I destroy them. I like the idea of filters, the way we’ve been taught history—it filters the way we look at reality. So I take images, and then I destroy them, and then I make up these slogans that are somewhere in between political statements, and then sentimental also. There is a lot of dealing with that, not only here but in most of my work. How we build our subjectivities, and how we are influenced by strong forces beyond us, like politics, economy. I like to present an image, and you first you see it as sentimental. Then you switch your glasses and look at it politically.

You can feel it or you can analyze it.

Yeah, and sometimes they’re smaller, sometimes they’re more complex. I like the fact that, either you see a big picture from distance, or you get closer to the facts and details and see different layers. So I like this idea also, this allegory of an image of history. Just a bunch of texture, it’s very complex for me.

It plays off the theme of the history as palimpsest, accreting all these meanings on top of one another.

Yeah, exactly.

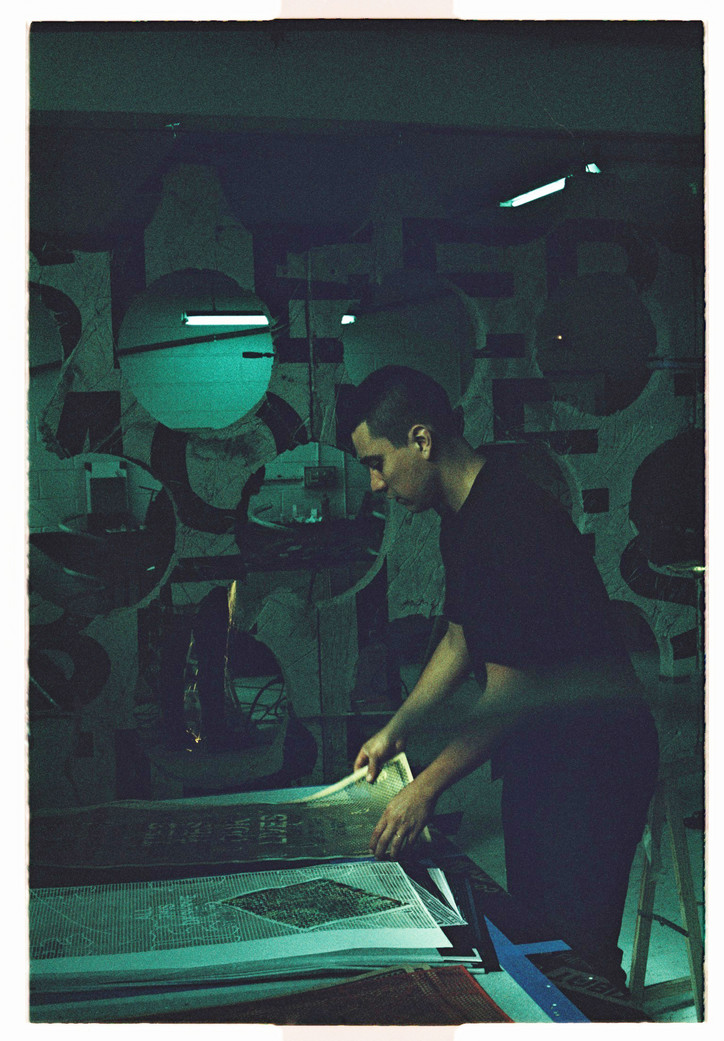

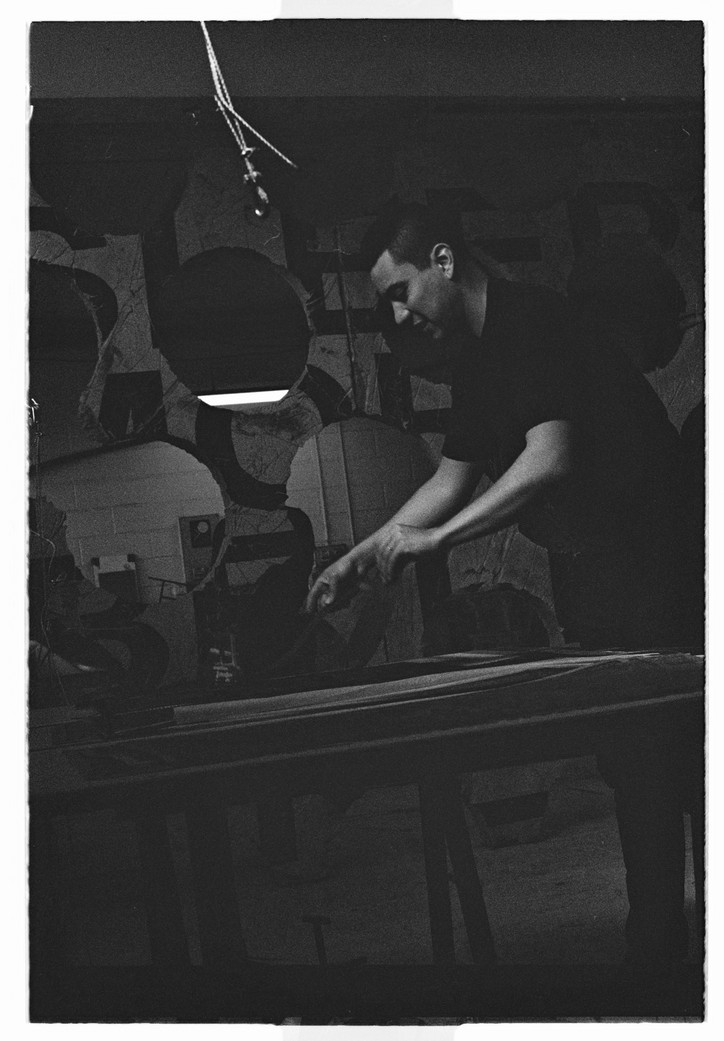

So in terms of your technical practice…

These are scans of pages of the comic book, and then I laser cut them. I’m very geek. It’s like a drawing practice, but mainly on the computer. A writing practice, a drawing practice. At some point, I produce a lot of material with barely an idea of what it’s going to be, and then I just play. Then there are works from another series, it started with my first film, actually. We made this action where we took a piece of wall and put it on the street, which has graffiti. I wanted to give some weight to these words, you know graffiti is kind of ephemeral, and I wanted to make a piece of archaeology out of it. In the beginning I kind of reproduced graffiti, but then it was not about graffiti aesthetics, it was also about writing, it became more about the text. I’ve started doing more and more of this writing, which is in between slogans and poetry.

The phrases in the show, are those from the comic? Or are those from you?

They’re more and more from me. But I pick them—for example I do a lot of workshops with children. I do protest workshops with children since 2011, because my parents were militant, and my first film was about, when they were young, they were part of these revolutionary communities in Columbia, in the ‘70s. I made a film out of these stories, because they have many stories which are kind of secret. During that research I found a picture of my dad doing protest in a primary school, with kids. I was like “What’s going on?” He said “Yeah, well I was a teacher in a primary school, and I was teaching kids to protest.” He’s still very engaged, actually he’s the director of the main left party in Colombia. So sometimes some slogans come from the children. For example, there is one that I use sometimes, that is “Sleep more to be less tired,” which is one that a child created, and I think it talks a lot about the work conditions today. It’s very childish and poetic. But the phrases in this show are more related to the film, and this idea of the other.

And then, uh…

Ah, the elephant in the room. The big gold sweet potato. I wanted to create this icon out of a sweet potato, to talk about globalization on a larger scale. Potatoes were distributed in the world after the colonization of America. They saved France from starvation, they saved Russia from starvation, and it’s always considered—well it’s not a divine thing, it’s not beautiful. So I wanted to create an icon as an opposite to the apple, the apple of knowledge—the last thing I made, it was about Newton’s apple tree. In England they keep the apple tree, and say it is the actual tree from the story. That theme is about knowledge, and progress, and it’s Eurocentric. People explain gravity to you with an apple, and not a papaya, or a pineapple. It means something.

There’s also religious implications.

Yeah, of course. Newton himself was very religious. Actually the story itself never came from Newton. It first appears fifty years after he died. Then later the government took this story and put it in the, like, the manual.

It’s back to the question of propaganda again.

Totally. So these films, and other films, are about patrimony. Some public sculptures I do, they’re about how government decided to point out some historical fact and make out of that some image of their greatness. So I wanted to treat this weak and imperfect potato in an iconic way. So, to put gold on it, which is kind of revenge too, because of the amount of gold that was taken from the Americas to Europe, so making a sort of precious divinity out of this weak root. Give it the respect it deserves. [laughs]

What are the earliest circumstances that informed the themes of your work? How long were you in Colombia?

I lived there until I was twenty-three. Then I moved to Paris, studied there, and then started working there. So I grew up in Colombia in different kinds of neighborhoods. My parents, they were schoolteachers, so I grew up in these kind of projects nearby, so I did my primary school in like a favela in Bogotá. And then, I did high school—it’s weird, my parents are super leftist, they’re super atheist, but I did high school at a religious school, because it was good teaching. I started school at 6:30am, and then I finished normal classes at noon, and then in the afternoon I did “technics,” because this school was also supposed to address popular classes, so you do high school, and then you’re allowed to work. So they teach you electricity, mechanics, technical drawing, graphic arts like printing.

So that comes in handy, for you.

Yeah. So I did school, and I specialized in graphic arts. The school was huge, it was a big campus, they have like five football fields, and so they produce bibles, catechism, these kinds of things, and we helped them actually, we worked in these places cleaning the machines, piling the paper, and learning photo composition, things like that. So then I did university there also, public university, in graphic design, and then I finish at twenty-one. I started very young, at sixteen. Then I worked in advertising, I was a director’s assistant in a big production agency, we were just filming, not creating the subjects. I worked there a year, making ads for Nestle, Mastercard, all that stuff. Then at twenty-two I participated in an art salon and got a prize. I was not in art, but I doing photography media, and I sent in these things, and I got picked. The prize was travel, wherever I wanted to go, three-hundred dollars, and a box of oil paints that I never used. I used the ticket to go to Paris, and then I learned French, applied to art school, got in, and continued there. I started working more, and doing shows in France first. I don’t know if that answers the question?

Yeah, that helps explain part of your path.

And then, so all my life, parallel to everything I was doing, I was also working in politics. Doing meetings, sometimes campaigning, because my father is an elected guy so we were campaigning with him, going to neighborhoods, serving drinks while he was talking, when I was a teenager I was doing that. I was packing meals for the protests, you know, “We need to pack a thousand meals!” so we bring all the yogurts and pieces of cake home and packed them up. Or my father also made newspapers, leftist newspapers, so we’d fold them and pile them.

So nuts-and-bolts organizing.

Yeah, yeah logistics and this—I’ve always been into that. I knew the places to print cheap in Bogotá. Meetings, protests, this has been all my life. When I move to Europe, I kind of separated from that, took a step back. It was healthy because it’s very engaging, and you feel bad if you’re not helping. At some point you feel selfish, because you should be contributing. At first it was weird, because my father started campaigning and he was like “You’re not here, I’m alone campaigning, and you’re there and you’re doing your art studies…” And I was like, “Yes.”

Did you find a great contrast in the way that the political atmosphere affected your daily life in Colombia, versus Paris? Did you get engaged, or were you curious? Did you get involved in politics in France?

When I arrived I remember the first week, I got contacted by people from the left who were living there, friends of my parents who were militants, or sometimes they were refugees, so I started getting in touch and working with this association that teaches French to Colombians, mainly women, who work there and who have been in Paris for years but who don’t speak French. I didn’t speak French much, but I was able to teach them a little bit better. But then, in like three months, I cut—I didn’t want to do the same thing, I wanted to get to know this other culture. I never felt I lost anything, I just won more, more information. I was very aware, I’ve always been aware—I used to travel by bus across Colombia because my father is from the south, near Ecuador. We used to from Bogotá to there, which at the time was like thirty hours. So we crossed all these towns, and my father is a politician so he’s always talking to me about the population, “Oh, this town is 300,000 people, the economy is based in sugar cane exploitation.” So I’m very aware of that, when I go somewhere I like to know, what is their per capita income, what is the main place where the money comes from, if it’s mining, agriculture, services. And also go into the street, be real, get in touch with everything, talk to the people, and have all this parallel information. So I guess that was my read on France, the cultures are different. You know, Parisians could be mean, or very dry, it’s different in Colombia, very warm. But there are interesting things, like in Paris people point out problems very quickly. If they don’t agree with something it is very quick, they do something, they say something. Meanwhile in Colombia you kind of put problems aside, like “Yeah, it’s okay,” until the problems become so big you need to solve them. Also I was learning French, because I didn’t speak a word before, so it was interesting to choose the way I wanted to talk. When you’re little you don’t choose, you kind of imitate. But then I was conscious about the language I wanted to learn, even the accent. You decide, I’m going to be a Latino speaking French, or I’m just going to camouflage. I chose the second one, I think it’s more funny. And then it allows you to access some details of language, the subtleties of tone, and jokes. Even the non-words. In terms of work, when I got to Paris I started doing a lot of interventions in the street, in the buses. I was kind of this martian in Paris, I’d never left Colombia before. I was alone, I didn’t know anybody, I was very happy. But I was thinking of this idea, to be alone with ten million people around, being alone together. So I started creating these interactions with people, like, how are they related to the art. The main thing is the difference between the treatment in France and Colombia, people treat each other differently. So I wanted to point out this thing, to approach the other, to talk to them, empathize with them, or shove them, or… Like, I don’t know if you’ve seen these videos I’ve made in New York, where people are looking back at me. I’m just yelling, very loud, “I love you, you’re beautiful people” at red lights, so people are like “What?!” But there’s no sound, there’s just the image, so you have this dramatic, almost like terror. When I started school, I was having questions about the relationship with art history. I learned art history, through Egypt, Greece, Rome, all these different things in Europe, and then pre-Modern art, and modern art, the avant-garde, conceptual art, and I was like “Why do they always teach that?” In the museum it’s like ok, it’s important, it’s great, there are great ideas, but there’s this and not other things from elsewhere. It’s very centralized.

And it’s very colonial in a lot of ways.

Yeah. So like, I saw Mondrian in photocopies all my life, in school, and then I got to see a Mondrian in real life, an I was like “Interesting, but why did I learn this from so far away, when I don’t know anything about pre-Colombian art?” And I don’t think I need to know it, I don’t speak Quechua, I speak Spanish, I don’t feel we need to be “revengist.” All history has been shitty, it’s been shitty forever. We don’t need to fight that, just be real and figure out how things work. So I made some works about the relationship with art history, I made this graffiti thing when I spraye painted over these two Mondrians at the Centre Pompidou. Which is fake. I made a video of it for the open studios in school. Since I worked on the production team, I spent a month adding frame by frame, drawing in the graffiti. Then the school director and teachers, they came and they were all pissed off, they were like "Iván, you don't do that in France, this is not the way it works here, this is vandalism, you're going to get in trouble." I just let them talk, and at the end I told them, "I tricked it. It's retouched."

Graffiti is an interesting topic in relation to your work, because it enables disenfranchised people to reclaim something that is often otherwise deemed public. You've spoken about how public spaces are supposed to belong to everyone, but nobody is really allowed to have an affect on them.

Yeah, it has a lot to do with the public interventions I've done, just the idea to negotiate with these images. Like, having a statue there, it's been charged with historical content, but then when you think about public space, it's a space we all own, but we don't have the right to affect it, it's only the city than can affect it. You con't have a right to put a bench somewhere, it's the city that decides. I feel, somehow, that's how individuality has been considered on a bigger scale. Like, "We don't give a shit about you, let's do practical stuff." Then it's like, we're supposed to pass this life, a very short life, without influencing anything. As individuals, at least. So this idea of renegotiation, it's important to me. It's not like I want to change the landscape of the city, or whatever, but it's like "Ok, I was born, and I have to carry all this story, and then I have your statue in front of my house." Why wouldn't it be allowed to interact with it? Add some content to it? Add a question to it?

Or take something out of it.

[laughs] Or take something out of it!

I just saw a headline recently, in New Orleans they're taking down a number of monuments that commemorate the confederacy, because there has been public outcry that they are symbols of hate and oppression, but the workers that did it had to cover their faces and have security, because there are also people there that are outraged that these symbols are being removed.

Yeah, it reminds me, you saw there was an election lately in France. Macron, the young guy who won, was in Algeria some months ago, trying to do this diplomacy, whatever, and he was interviewed by a TV channel. Algeria used to be a French colony, so they asked him about it, and he said “Yeah, you know, colonialism is clearly a crime against humanity,” and then moved on and talked about other issues. But people in France were so pissed! They were like “What the fuck?! French people died in that war!” and, you know “Of course slavery is bad—but it was good also.” So weird. So he had to backtrack. I was so shocked, general opinion was pissed that he said colonialism was a crime against humanity.

Yeah, it’s like you can’t be that honest. Especially because people don’t want to feel that shame. It’s insane the level of hypocrisy it brings out of people. But so much of your work is about the public, and the shared—how do you fit that into a gallery space?

I consider myself more like—I’m making a weird comparison, but think about like, Gabriel Garcia Marquez. He was a journalist, and all his novels talk about details on how all these towns during colonial times were developed. How the train got into the Caribbean, how the ice got into the Caribbean, and then he developed love stories, romantic stories, kind of dreamy stories around that. I was never directly inspired by him, but in time I see myself as sort of a fictional writer. For example, these films I do, or the sculptures I do, I think have to be considered pieces of fiction, or accounts. I’m processing a certain amount of information, and then setting up these small stories, which have their own narratives. Not a linear story, but a contemplation of things, a reflection of things. For example, when I finished graphic design, I was doing film courses as well, and I wanted to study philosophy as well, because I was hooked on philosophy. I like this idea of generating questions—but then I was like, philosophy is only about language. You’re reading, you’re writing, you’re reading, you’re writing. Then I was like, thinking is richer than that, we can think through movements, through dancing. That’s why I wanted to go to an art school. It’s maybe the closest place where I could explore this sort of, empirical philosophy or something like that. So I think this all works inside, outside, they’re kind of statements, or writings, or positions, or questions, where either you look in a library, or out in the field.

It’s like the parallel knowledge you referenced earlier, when your dad told you the factual overview of a town in the context of the country, alongside the experience of going into the streets and meeting the people.

Yeah, and I never intend to fight the status of the places where I work, I rather try to use them as tools. I’m not going to fight against the museum, because I understand why the museum exists. And it has its problems, and it has its advantages. So what I’m trying to do is just use it as the right tool, it’s not like “Yeah, this is shitty. I don’t like it.” This kind of institutional critique is not my thing, I’m more into a progressive, positive…I try to negotiate. I think it’s also part of the political teaching I was given by my parents, because my parents were very radical in the ‘70s, they were part of the guerrilla, and then they moved to unions during the ‘80s, then in the ‘90s they started, when Pablo Escobar died and president Gaviria made a new constitution, it allowed small parties to be created—before it was only two parties. So they moved to unions to create these small parties, and then in 2000 they joined all together to make this big party. So during these thirty years I’ve seen that from very close, seen how they’ve been learning to negotiate with the reality, because at the beginning they were just completely radicalized, like “No, this is not going to work, we are not going to participate in democracy, this is bullshit, and we’re going to take the power back and make it socialist.” And then they started interacting more and more and more to solve things precisely, in a neighborhood for example. It’s not like “We’re going to take power and make Communism!” That’s pointless, that doesn’t bring you anywhere. So they’d been learning that, and that’s what my dad has been trying to do—he’s radical, he’s not complacent, he never colludes with any industrialist or politician from the right or anything, but he’s pragmatic, which, sometimes the left misses the pragmatism. Even Lenin, he has a book called The Sickness of Leftism Inside the Communist Party or something, and it was mainly about how extreme leftism could block you out from reality. But my father was good at parenting, because he's a negotiator. He never had to yell at me. I was never punished. I was free to make all my decisions, since a very early age, I just had to share the information. The thing was not like “Oh, I’m going to be punished,” but they’re going to be disappointed if I did something wrong, or something stupid. Because they trust so much in me, so when I disappointed them, when I did shitty stuff, I remembered it.

How did you connect with Perrotin?

I arrived in Paris in 2006, and by 2008 I was already in school, and had done a solo show in Berlin, a solo show in Bogotá. I left one life in Colombia, I had work, I had friends, a girlfriend—I left this life to do a new one in Paris, to start again. So I was very engaged in school, I didn’t come there to have fun, party, take drugs, I already did that in Colombia, so I was very focused. In 2008, of course the gallery was already very well known there, and had great artists doing shows with the gallery but also museums at the time, geletin collective, and so I approached Emmanuel [Perrotin] at an opening and said “Hey, I really like what you do with your gallery, I really like the energy.” I think he was surprised, because nobody talks to him like this, much. I said “I’m a Colombian artist, I’ve been here for two years, I’ve been doing shows here and there and I’d love for you to see my work.” He said “I’m going to be honest, I don’t have that much time to see students’ art, I don’t do studio visits, I only work with established artists, but I’m going to give you my card. Send me an email. Most probably I won’t answer back, because I don’t have the time, but don’t be pissed. If I don’t answer back, it’s not because you’re bad or something, it’s just that it doesn’t work like that.” So some days after I sent a very short email, shared my website, very short. I didn’t expect anything. Three months after, I got this answer, “Could you come to my office, Wednesday at 11?” Yeah, sure! So I went there and had a short conversation, showed some videos and websites I did, web art and programming things. He liked the works, the interventions, the cheeky part of the work, and he was also very interested in the programming. He also was very curious about, “You were raised in France?” “No, I arrived two years ago.” “But you speak French?” “I learned very quick,” and he was very curious about that, and then he said “Do you want to collaborate with us?” He was planning to make a group show with young artists, and wanted to include my work. He said “Please don’t get your hopes up, this may not work, but let’s give it a shot.” So we ended up doing the show in Miami, and we kept seeing each other sometimes, and he’d ask me for news, I would share my work sometimes. I’d been doing my stuff on my own, and I got prizes, I got scholarships, I got residencies, I started having shows at institutions, and at the same time Perrotin started collaborating more and more with me, and since around 2011 I started to integrate with the gallery in a more official way. I’ve always had a very different relationship with them—for example, none of them have seen the film.

That’s very trusting.

Yeah, there’s a lot of trust, a lot of respect. Very professional, so I have to learn very quick how to deal with time, logistics, transportation, because they work on a big scale.

Well the easy parallel to draw is with your parents, right? Then and now, you alone have to answer for your actions.

It’s true.

La Venganza Del Amor is on view through June 11 at Galerie Perrotin, 130 Orchard St. in New York.