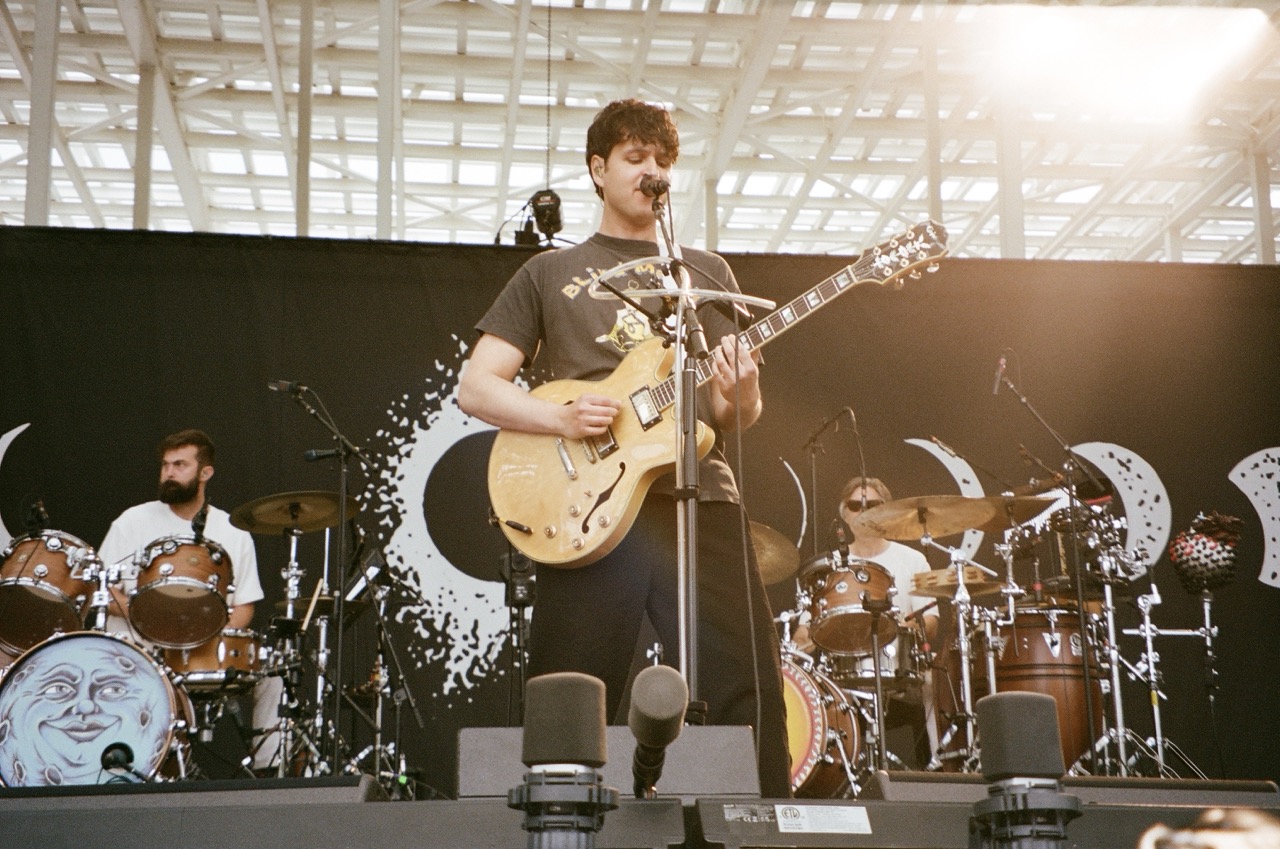

SHOT: Nick Zinner in conversation with Barnaby Clay

NICK ZINNER: So, this is probably the biggest thing you’ve put out into the world.

BARNABY CLAY: It is, it is indeed. I’ve done short films and gone to festivals here and there, and I did that documentary years ago in Russia for my friend’s band. I think that was in 2003.

NZ: When did you get into film, or filmmaking? Did you study?

BC: Yeah, I did. Well, first I went to art school in London. And at the time, basically if you wanted to study film, there were two film schools in England, but none of the other art schools or universities offered film courses. It’s crazy. Now, everywhere does it. But back then there was nothing.

So while I was at art school, I actually made my first proper film that I wrote, shot, edited. It was a twelve-minute kind of a horror, sci-fi, culty, weird film. But it was funny, because while I was doing it, all the teachers just thought I was skiving off the whole time. There were no film facilities at school, so I was just off doing it by myself. I don’t think they really believed that I was doing anything until the end of the term when I had to show it.

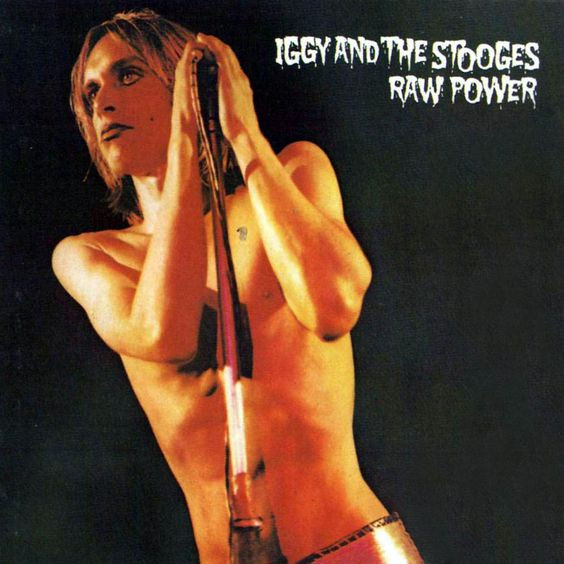

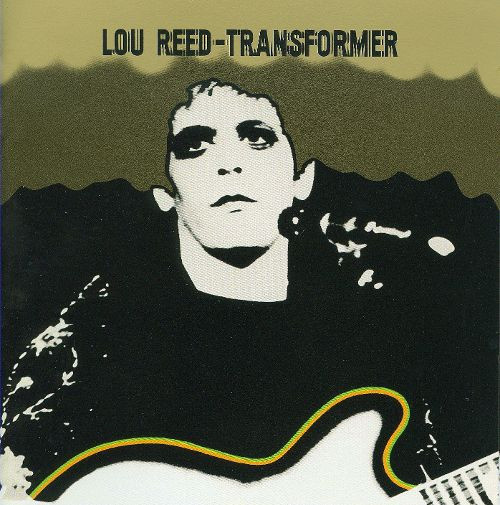

I was at art school, but as much as I liked what I was doing there, there was no real way to do film. And so I went to film school for a bit. Interestingly, and I said this in some interviews yesterday, my real film school was basically the place where the cover of Raw Power and Transformer were shot [by Mick Rock], the Scala Cinema in Kings Cross, London. When I was growing up, it was the coolest, most weird, skuzziest, punk rock venue. And they’d play cinema. Every Saturday night it was like all-night, psychedelic madness, and it was amazing. It was like three pounds fifty to get in for the whole night, and you’d just sit there, take acid and watch movies. That was really my education. [Laughs]

NZ: Yeah, I played there and went to a party there. I can really visualize it.

BC: For me it was really sad that it became a music venue even though it was one originally, and of course I flipped out when I found out that Raw Power and Transformer were shot there, because of course in my teen mind thought it was shot in some scuzzy joint in Detroit. And then Transformer I thought it was—

NZ: Max’s Kansas City or something.

BC: Yeah! And it turned out to be this place I’d been going to for all these years. But yeah, I’d go and see these movies and you’d hear the trains. I remember seeing Eraserhead and it was this whole extra element, a sort of industrial soundtrack. And the cinema would be shaking. It was so cheap to get in there and it was like a really run down area at the time, so you’d have homeless people coming in just to get out of the cold, to watch movies or just sleep.

Album covers for Raw Power and Transformer, shot by Mick Rock

NZ: It’s funny how two very different aspects of your life could come from that place and return to that place. So, you’ve always been a music fan as well, we’ve talked about that a lot. Is that what lead you to do music videos after school?

BC: Yeah! I mean, I came in at a weird time for music videos. In my mind I came in at like the tail end of the Golden Age. It was when Spike [Jonze] and Chris Cunningham and all those people were kind of ruling it. I was just starting, but they were already there.

NZ: Mid-nineties?

BC: Yeah. And some amazing stuff was being made, so for me it was just a really interesting platform to learn about making films, or just filming in general, and the whole process around it. So much cool stuff was being made, and I would just look around and be like, holy shit.

Pretty soon after I started, and of course you're really familiar with this, there was kind of the Internet takeover and invasion of music. So everything folded, and the budgets started coming down. When I started, I did some videos with pretty decent budgets. The kind of budgets they use today used to be reserved for like the tiniest, tiniest bands, whereas now a pretty well-known band can still have a really low budget.

So I did manage to get involved in that in the very beginning, but very soon budgets started to drop. You can still do great, creative, work though.

NZ: Limitations are good.

BC: Yeah, they’re always good.

NZ: Well, I think they’re creatively good.

BC: Yeah, it forces you into certain places where you have to figure your way out of something, where you can’t just throw money at it.

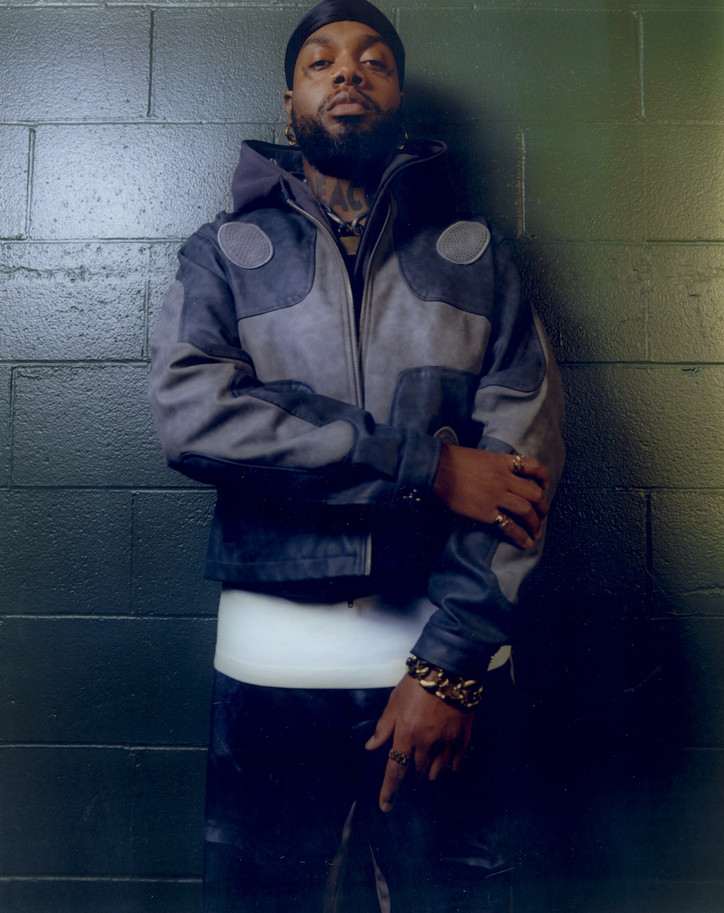

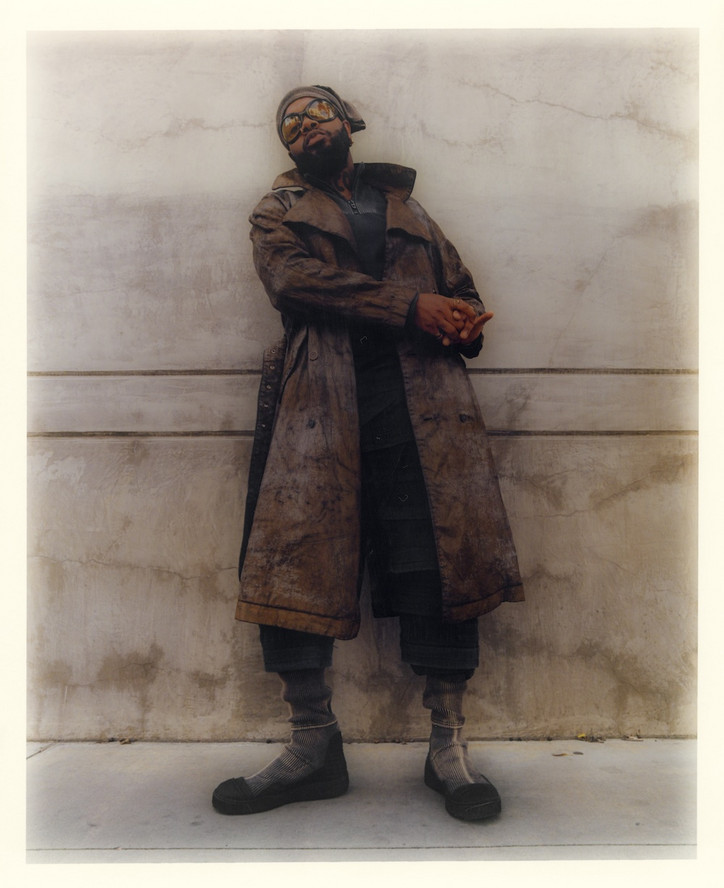

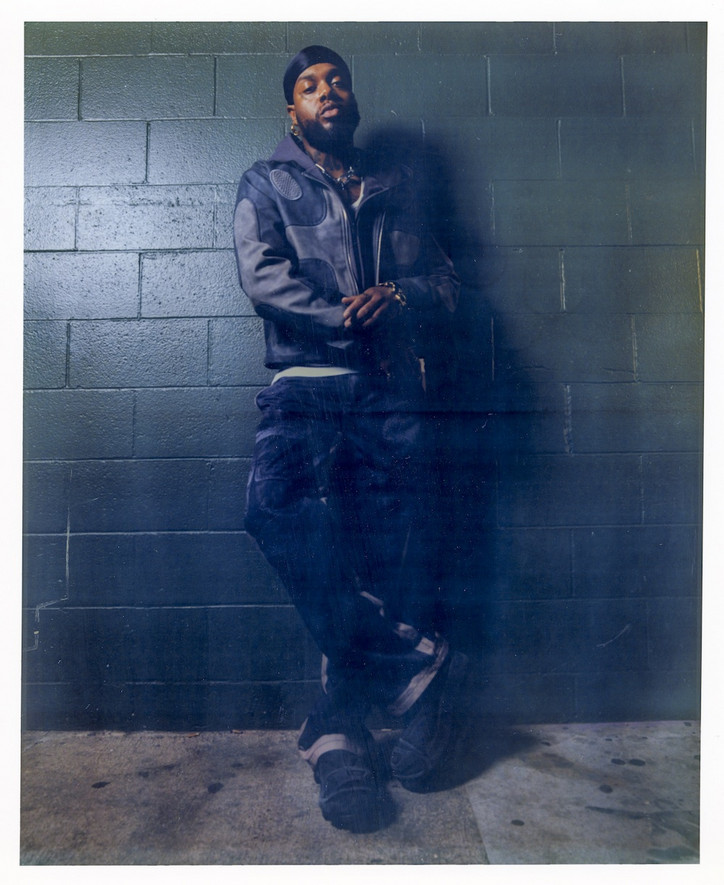

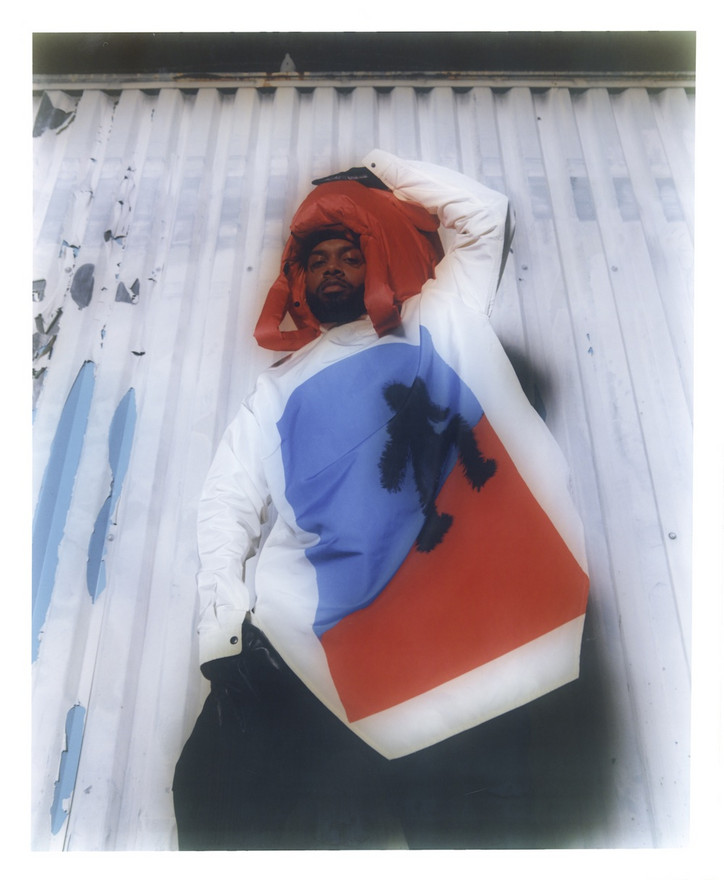

Barnaby Clay, shot by Nick Zinner

NZ: You have to be tough, when it’s your vision. So, what was your vision for this documentary?

BC: I really wanted to make a film, so I wanted to see if they would trust me to make something different. There were a lot of ideas, and there was one I was interested in that would have been pretty difficult—

NZ: Puppets.

BC: [Laughs] Yeah, puppets. No, but it was all going to take place in a diner or a dive bar or something like that in New York, and it was just going to be like—what’s the funny series of paitings? Rock Dreams? There was an artist [Guy Peellaert] who did all these fancy pictures of celebrities, some living, some dead, all hanging out in some places together. It was kind of like that in a way. So basically everybody in this diner or café would have something to do with the film. So someone like Iggy Pop would come in and sit down and have a chat with Mick, or Debbie Harry would be the waitress.

NZ: Recreating her job at Max’s Kansas City. [Laughs] I always feel like creatively, sometimes the most challenging thing is that first step, that first moment. It presents all the steps you need to take and the way the film wants to be.

BC: I think as long as there’s some people who recognize that you’re doing what you’re doing for a reason, and not just to look cool, it’s good. It never starts with that. It starts with, “how do tell a story differently?”

Ultimately, with Mick’s story, and as amazing a photographer as he is, and as interesting and funny character as he is, his story is a pretty old story. It’s been told a million times. It’s like Icarus, it’s the oldest story in the book. So how do you tell that differently and make it interesting? You have to try.

NZ: So how did you end up doing that? Did you have a vision for the entire film, or did you start somewhere and decide to see what would happen next? Did you plan things out with Mick, or did you work in chunks? Essentially, did you have a vision of the finished product from the beginning, or did it change throughout the process?

BC: I basically had the central idea at the beginning, which is that it’s going to take place in this space which I kind of saw as Mick’s psyche. We get taken into this operating theater at the beginning of the film, which is obviously a stylized version of Mick’s psyche, and that’s where we spend the rest of the movie. So that’s the basic idea. And then from there I was like, what else do we need to do? I want to show him going through his stuff, going through his work. I want to show him working.

NZ: But all within that space, right?

BC: Yeah, I liked the idea of being within that space. Obviously I couldn’t keep the entire film there because that would be too much, so I had to use another tool to get me out of there, basically.

The earlier cuts were way more arty and weirder. I was going for this memory-based approached, and it was kind of too weird for most people I think. I think if anything, the main things which changed throughout was just it becoming more chronological. More conventional in a way, I guess. Mick had done a lot of books, a lot of interviews, tv, radio, magazines, for years and years and years. He’s well-trodden in telling these stories. So he kind of thought it was just going to be that, that it was enough to just tell these stories about his work. But I think the biggest struggle was basically us—as in myself and the producers—persuading him that it needed to be more than that, that it needed to have a personal feel, that he needed to open up on the personal side of things. You can’t have ninety minutes of just talking about pictures. I mean, you can, and there are a lot of things like that.

NZ: From his point of view, it’s probably hard to let go of that idea as well. To his credit, I could see how that could be a difficult thing. It’s his life.

BC: Definitely. And it was really probably a year or two on and off of shooting, but most of the time was spent in editing. And much of that time was really a continuing argument between Mick and myself about those kinds of things. And some of it was me wanting to keep ahold of things that I’d shot because I liked them a lot, and some of that was Mick not being ready to open up. It was difficult. It was a constant process of argument and going back and forth, until the end, basically. I guess for me, when you’re in it you don’t really see it, and I had to remind myself—or Karen would remind me—that this is his life story, that this is somebody else’s life and you have to listen to them. Even though they have no objectivity, you have to listen to them because it’s their life. They’re the ones who have to live with it. And I mean my thoughts were that I have to live with it too, I’m a director and I’m going to be labeled based on my work. So it was difficult.

And that central theme of him nearly dying became very contentious as well. At first he was really into it, and he came to all the shoots and did all this stuff, and he was kind of intrigued by it. He didn’t really understand it. He was like, “why are you doing all this stuff when it’s about pictures?” But it wasn’t just about pictures, it’s about him. But then when he saw it, he began to kind of get more and more concerned by it, because he found it uncomfortable to see himself that way.

NZ: Another thing I was really curious about was how you achieved this balance between these classic songs that we all know, space, and the score that [Steven Drozd] did. Because I love the score, but it’s very difficult to make a score for a film about music and keep everything in balance without one thing overpowering the other. So what was your interaction with Steven like?

BC: I knew that the film needed a score beyond the rock songs, that it needed something to bind it together. And I knew that that couldn’t just be straightforward rock, because it would be too much. And we talked about influences, and [the score] kind of went for that period a bit, but more on the avant-garde side of it. We talked about Wendy Carlos, we talked about [Brian Eno]. And it’s actually really hard, because when you’re editing you’re always putting in temp music and you get very attached to that temp music, and then you’ve got to swap it out for something that has the same feeling. So you find yourself in kind of a situation where you’re kind of copying the temp music, and you shouldn’t do that.

I actually remember one point when I was working in the Flaming Lips studio in Oklahoma, and [Wayne Coyne] turned up. He’s quite challenging. He was basically saying how there was one piece of music he really liked, but there was another piece of music that we were working on at that time, and he was kind of complaining—rightfully, actually—that I was getting Steven, who’s a very talented musical mind who can do anything, to just do Queen. And that’s the temptation—oh, we’re in a kind of Queen era, let’s just do Queen. So after Wayne said that, we kind of threw that out and went back and tried to consciously do something that wasn’t just Steven mimicking these periods of music, and trying to actually make a concise score.

There were two sessions where we worked in their studio in Oklahoma. Those ended up being some of my favorite memories of making the film, because watching a multi-instrumentalist like Steven running around is amazing.

NZ: And it enables you to see the film from a different perspective.

BC: Completely. And you’ve done a lot of score stuff yourself, so you know—

NZ: That it’s a process. [Laughs] So, now that it’s finished, how do you feel? How do you feel about the fact that it’s going to be seen by people, that you can’t fix it anymore, and that it’s time to let it go and move on to what’s next?

BC: Well, I feel excited at the idea of moving onto something new. Obviously, and you know this from doing your records, that you can fix and tweak and change until the cows come home, until somebody eventually says “that’s it.” Even in my final sound mix, I was just sitting there and I’d have three pages of notes, I’d go through the whole film and do all those notes, and then there would just be another thing to fix. Shit man, it’s just never ending. They’re small details that maybe nobody will notice, but at the same time they make the bigger picture. But you do have to let go, and so I have let go.

I will say, to round it off, that through the hardest moments I had making the film, and the hardest hours, I would get into the edit, and I would be going through a sequence or whatever, and every time—this still happens—I’d be knocked off my feet by what Mick did. No matter what beef I had with Mick at any particular moment, his work really stands on its own. It’s amazing work, and it blows me away, the breadth of it and the accomplishment of it just being a visual encapsulation of a whole time period—arguably the greatest period in rock and roll. And he’s still going, still going strong. But I would just see those images, and it would just remind me of why I was doing this film. These pictures need to be talked about. They’re works of art, and it’s a pleasure to be the person who gets to tell the story.

Barnaby Clay's film, SHOT: The Psycho-Spiritual Mantra of Rock, is playing at Metrograph through April 20th. Tickets are available here. The film is also available on iTunes and Amazon video.