Visual Narratives from the Black Rest Project: Rest Is Power

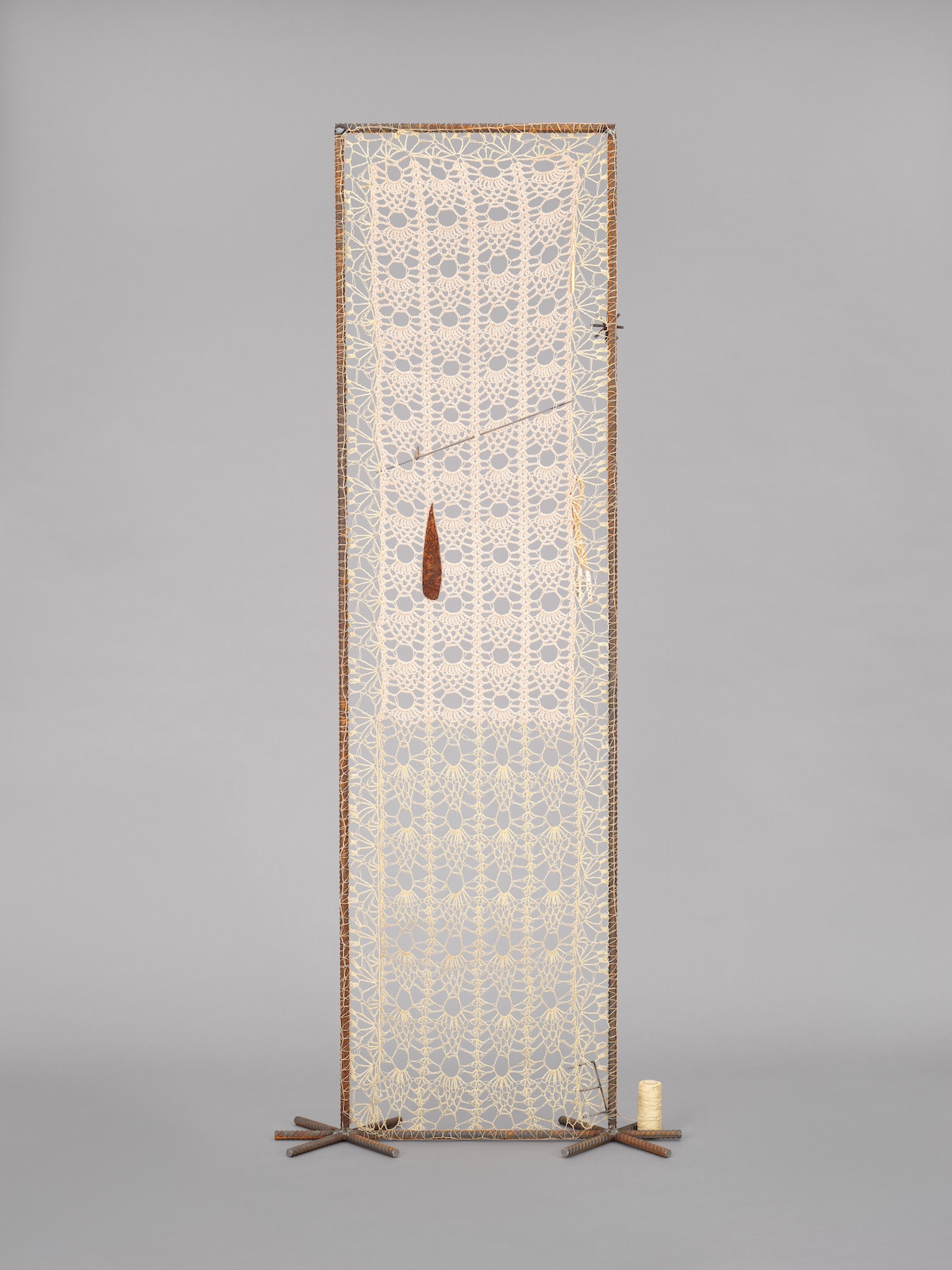

Through photographic portraits, landscapes, and scenes of domesticity, the exhibition features visual interpretations of rest by artists Tyler Mitchell, Allison Janae Hamilton, Daveed Baptiste, Gordon Parks, Carrie Mae Weems, Colette Veasey-Cullors, Cornelius Tulloch, Chester Higgins, Lola Flash, Kennedi Carter, Jeffrey Henson Scales, and Adama Delphine Fawundu, among others.

After the opening, office spoke to two of the curators of Rest Is Power, Dr. Deborah Willis and Dr. Joan Morgan.

Samuel Getachew— I was fortunate enough to see the exhibition on opening night, and first and foremost, I want to say congratulations. It was so moving, and so beautifully curated. I’m heartbroken that I couldn't make it to the artist’s roundtable on the 12th, but I’d love to hear how it went — any highlights you can share?

Joan Morgan— Well, it was really well attended — it was standing room only, which I guess isn't that surprising given who was on the panel. In addition to seeing these amazing artists present on their process and their craft, and give their thoughts and reflections on rest, I think the highlight for me was to have Tricia Hersey actually be able to see how her work is being taken up in the world, and actually have that engagement in real time. Often I think when you create things you hope but you don't necessarily know how it is not just being received but actually being engaged.

The most moving parts were the questions from the audience, about their own breakthroughs regarding issues of race and gender and giving themselves permission to rest. People shared how the art in the exhibition and Tricia's book and some of the artist statements felt like they were giving them permission to heal and to rest and to set boundaries, which of course is our overall goal and ambition with this project.

Deborah Willis— There were actually two doctors in the room that we didn’t know would be there. I was so impressed with them sharing their moments of what the exhibit meant to them. As doctors, people don't see that they need rest too. When a patient comes in, they have to get up and go back to work, if a patient dies, they just have to get up and go back to work.

Some of the questions also talked about the grind culture that we experience as these artists, that we need to keep moving, we need to keep working. In Europe, there's support for the arts, but in the US rarely do our artists have grants or government support from their country. That was another aspect we hadn’t thought about.

I know Tricia’s work was very foundational for the concept behind the exhibition. Can you tell me more about how the idea for the exhibition came about?

JM— Every year thematically, we come up with a topic that we’re going to explore at the Center for Black Visual Culture. Our first one was Black joy as resistance, and our second one was redefining home, but we felt like we actually needed a 3-5 year commitment, and we wanted to come to work collaboratively outside of the walls of NYU.

The exhibition is the launch of our larger initiative, the Black Rest Project, which came about quite honestly because Deb and I had just come out of two years of virtual programming during COVID where we were often running two programs a week virtually. For a time when we were all supposed to be locked down and standing still, we emerged from it pretty exhausted. I noticed that was basically everyone's response: really exhausted and depleted, and even more so for people of color.

DW— We as an academic body needed to focus on rest. Joan, Kira [Joy Williams] and I decided to put together an advisory committee and to invite scholars who we knew were going through the same questioning, ask the questions, “What do we think about it? How do we talk about it?”

JM— The exhibition is our first attempt to amplify visual narratives of Black rest.

Do you see the Black Rest Project exploring non-visual mediums in the future?

JM— Oh, absolutely. That's why we brought in collaborating partners, and we're about to meet with the advisory council again. We're working with various factions — historians, scholars, activists — many of whom don't necessarily work in visual culture but have real ideas about how to bring rest back to their community.

The exhibition features a really diverse range of artists, some much more established like Gordon Parks and Carrie Mae Weems and some who are quite young, like Daveed Baptiste. How did you make those curatorial decisions?

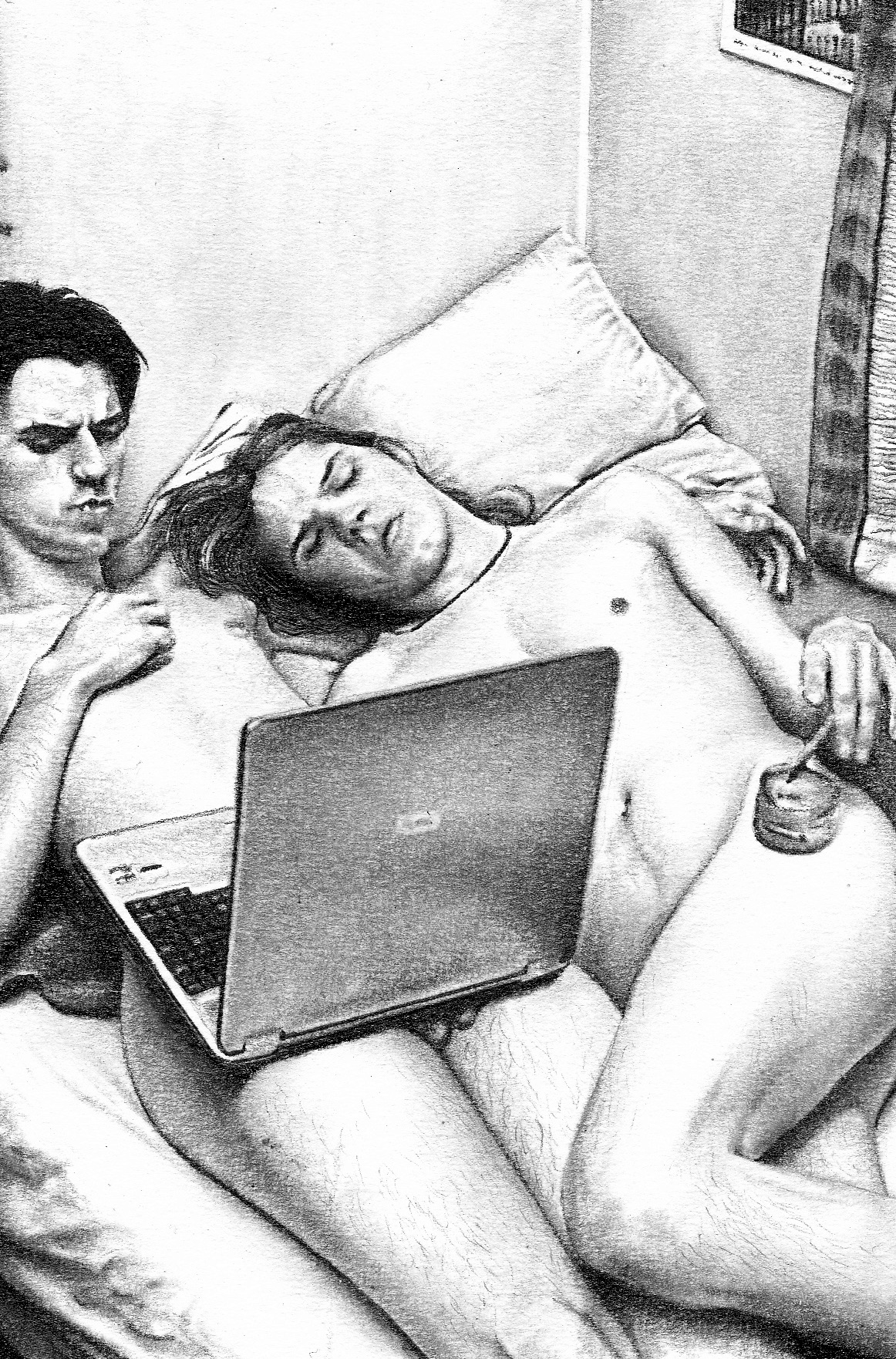

JM— We learned a lot about what we each thought about rest in going through the images. We had some really robust debates about what was restful, because we became very aware that what looks like rest to one person may absolutely not look like rest to another. It expanded our ideas.

With the photo of a barbershop, I was like, “Why is an empty barbershop restful?” The barbershop looked like a place of labor to me. But then Deb explained how much goes on in Black hair care spaces, and also how that moment when there are no customers and you're closing down for the night is the moment right before rest. I learned a lot because I wouldn't have necessarily picked that image, but Deb went right there also because of her experience growing up as the child of a mother who owned a beauty salon. We had to really expand our notion of rest beyond just, like, Black bodies sleeping.

DW— We decided to invite people to send work, as well as look at some of the people that we know and go through their archives. The range started with younger artists that I met in different cities. I travel a lot, speak to a lot of photographers, and they send me portfolios and ask me to review their work. I didn't ever think that I'd be working with them on some projects, but I thought, “oh, this is a good person to keep in mind.”

There’s some images that reevaluate rest from my own memory, from the collective memory of the three of us. There was also the worthiness that I felt of the photographers who took the time to make images, like the Gordon Parks image of a woman looking out the window in Harlem with her dog. I felt that it was necessary for us to explore.

The photo that stuck with me the longest was Kira’s photo, of her father and brother embracing. It was the only work that I saw representing fatherhood, which was striking and thought-provoking in-and-of itself. Are there any works that stand out to you?

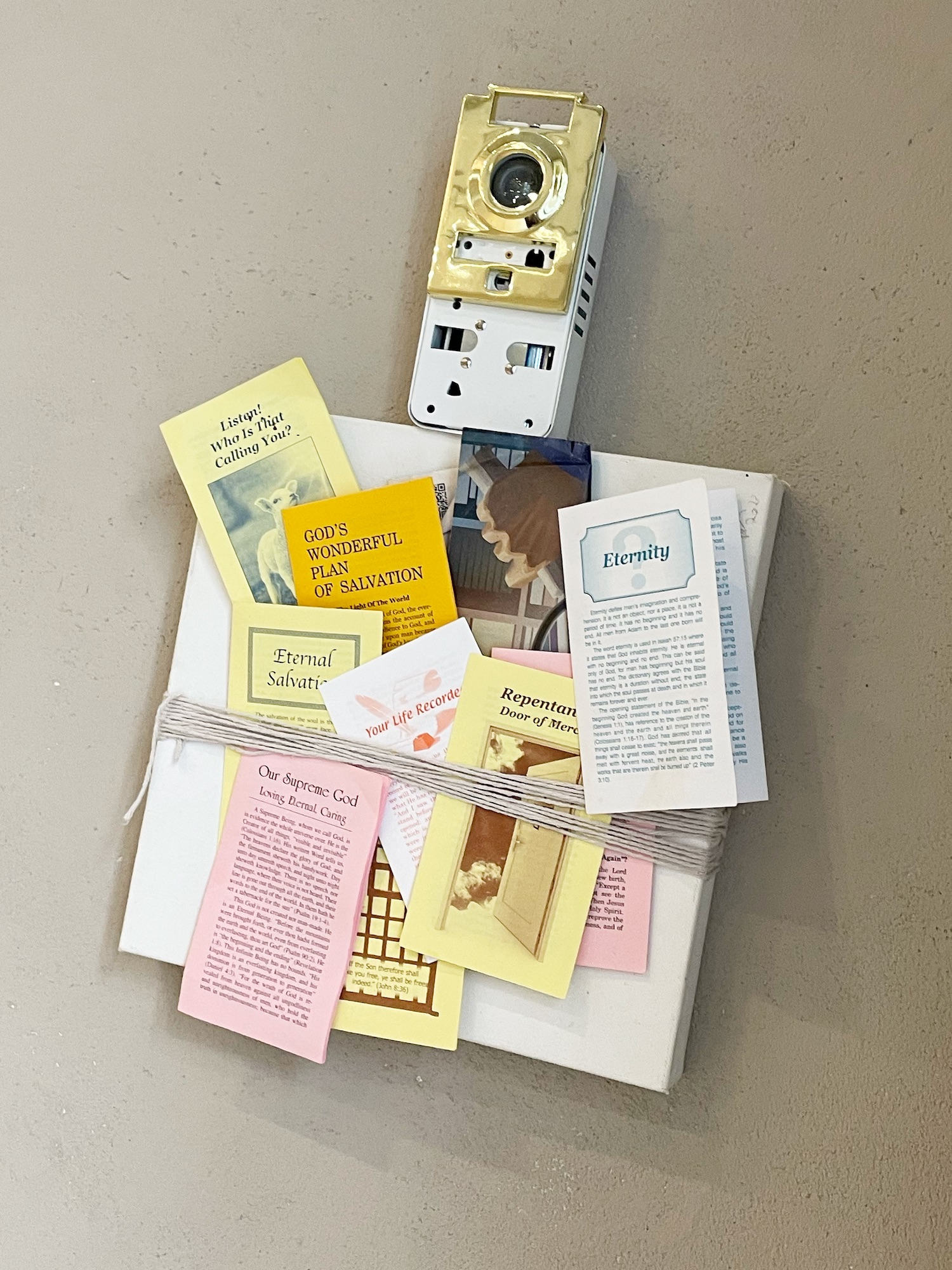

DW— One that touches my heart is Daveed’s mother reading the Bible. I unfortunately lost my mom this year, but my mom was 100 years old. She loved her peace and she loved reading her Bible. And one of the projects I had when my mom was in her eighties was that I wanted to photograph all of the women that she went to beauty school with back in the fifties. I rarely show my work in a show that I curated, but I felt that my words and my images needed to be together in this exhibition.

One of my favorite photographs is of my mother's friends, who were caregivers taking care of others even in their nineties, having an opportunity to rest. I love how relaxed the woman looks in the shampoo chair. When I connect my own mother’s experience to Daveed’s mother in this beautiful white slip reading the Bible, it just had a real effect on me as an image that just helped kind of guide me through this process of loss.

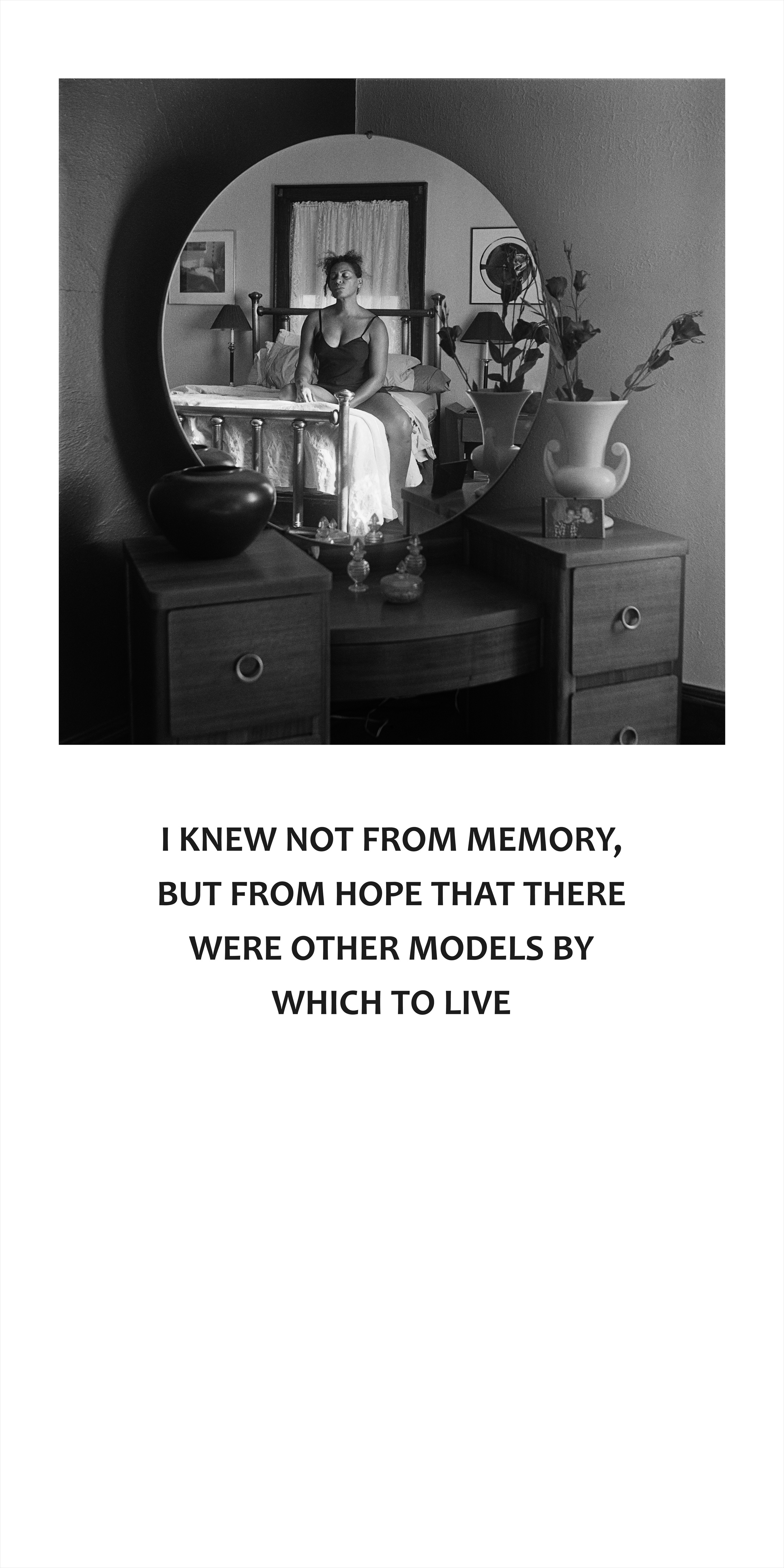

JM— The painting is obviously one of my favorites. It's deeply personal to me — the woman in it has been my closest friend since I was 13 years old. It's a portrait of her and her daughter, who is like my niece.

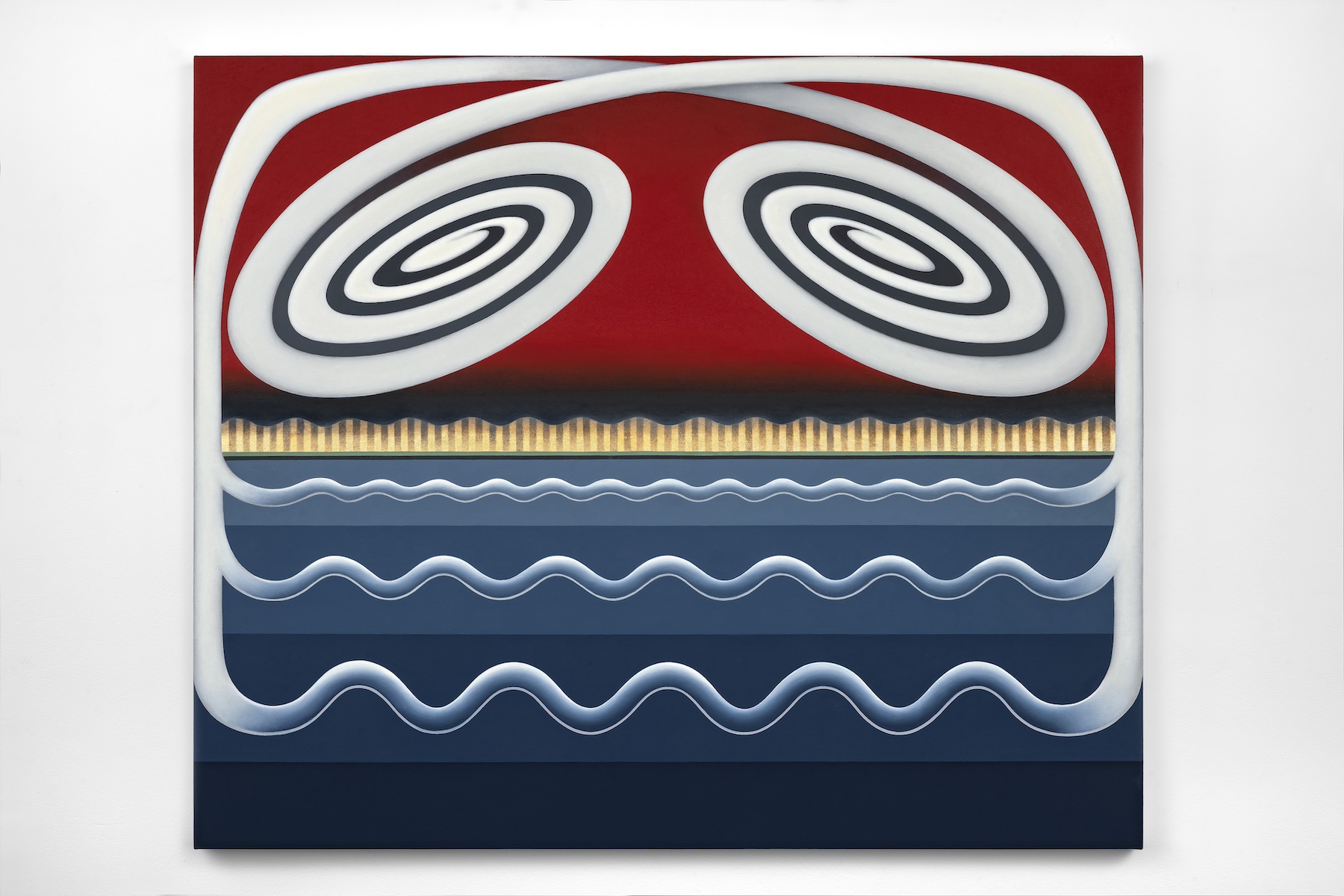

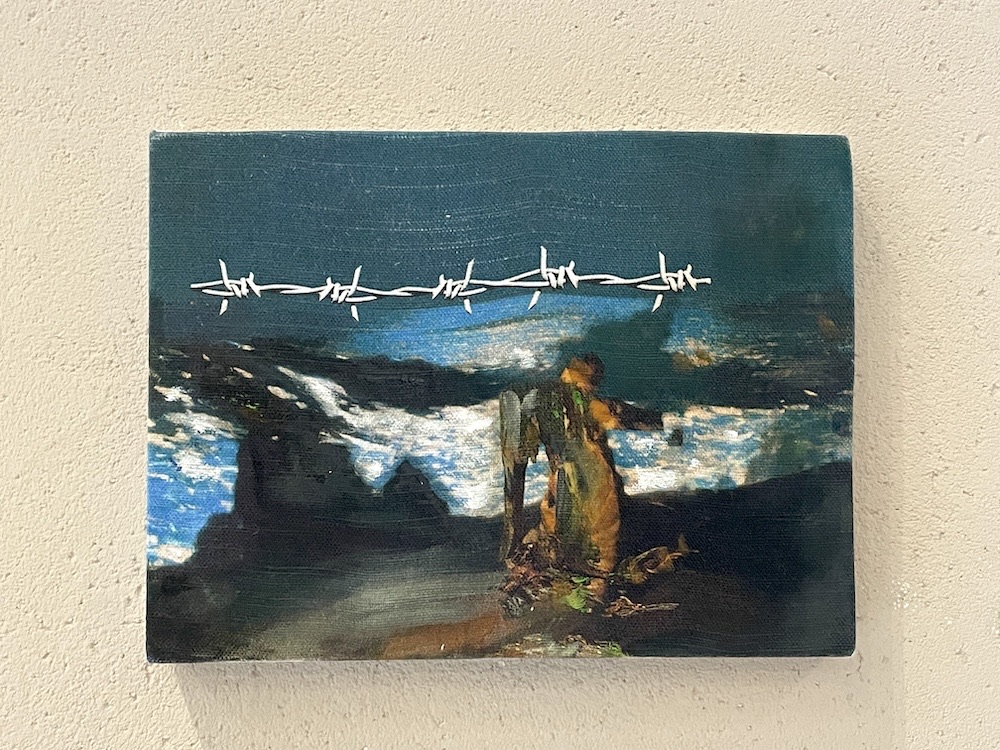

But the standout isn’t just one piece – I would have to say that it's the progression on a particular wall. The way that water sort of flows from the Chester Higgins piece to the piece in the boat over to the wall of Lisa Leone’s portrait of me in the ocean, to Renee Cox, with the reclining in the pool, to Cornelius Tulloch’s work. It spans the diaspora, we're talking about Africa, we're talking about Jamaica, we're talking about Miami. I just love that little section of the exhibit so much, I find myself walking it back and forth fairly often.

That must be so rewarding as a curator, to see works in dialogue with one another like that. What are your hopes for how people engage with it?

JM— We’re not a gallery that’s on gallery row in Chelsea, we’re literally in an academic space. Nothing promotes grind culture more than academia to me. I'm hoping that from now to October 22nd, that it serves as a kind of disruptive reminder to challenge that. And I mean that from students all the way up to the upper echelon of academic power — come in and remind yourself to give yourself grace to rest.

Rest Is Power is open until October 22, 2023 at The 20 Cooper Square Gallery.