Where Joseph Cochran II Fits In

“Find the beginning,” follows Wilson’s wording. Joseph Cochran’s beginning is his lowest point. After he and his shared Bed-Stuy apartment fell victim to a gunpoint robbery in 2011, Cochran was “on nothing and doing absolutely nothing with [his] life.” A friend gave him a camera, no strings attached, with no strings to pull either, and so he took off, leaving the pack to chase a different path.

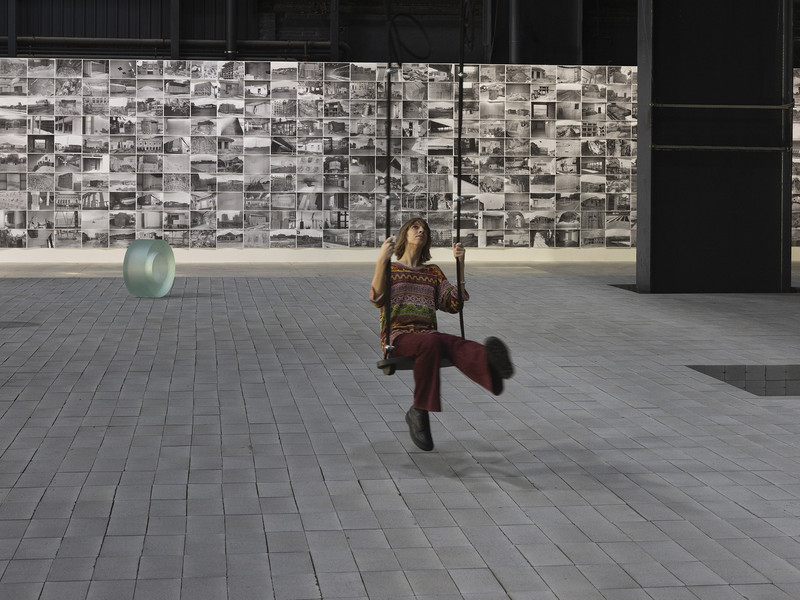

A decade later, the man returned an artist; a photographer; a researcher, but above all, a storyteller. In its horn of plenty, Forays, Frontiers, and Flags — spanning 12 years —is a comprehensive display of Cochran’s footsteps across the globe. comprehends Cochran’s footsteps across the globe. Throughout his escapes, he continuously found himself in places penetrated by systematic instability, censorship, or challenging change. Amongst the events are China’s resurgence to superpower, Hong Kong’s fight for freedom, the migration crisis in the Mediterranean, and the ever-so-chilling effects of the pandemic — none of which were exposed but experienced through Cochran’s patient explorations. Thus, his work allows the viewers to do the same — not just to look but to interact.

“Where am I now? Are those who live here violent and cruel? Or are they kind to strangers, folks who fear the gods?” continues Homer’s poem, and thus Cochran’s practice. His sensitivity spots the nuances, focuses on the impacts, zooms in on understanding, and flashes the truth. He blurs the boundaries between diary and documentary.

In times when images are exhausted everywhere and oftentimes all too empty, while both the trust and credibility for institutional media continually decrease, Cochran's images stand out. They place themselves at a great distance from the flat and from the false, and by doing so, also archive a sincere sense of urgency.

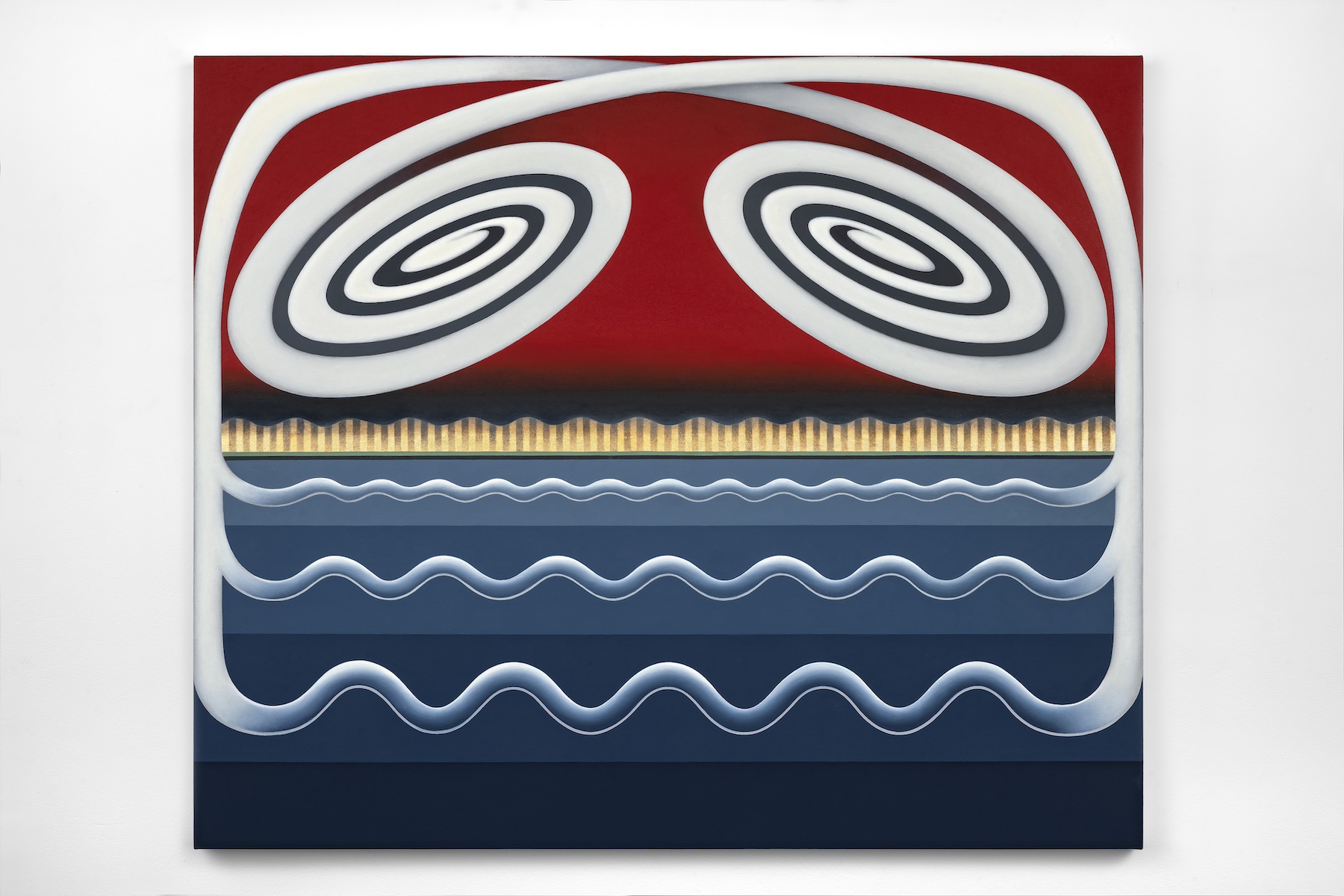

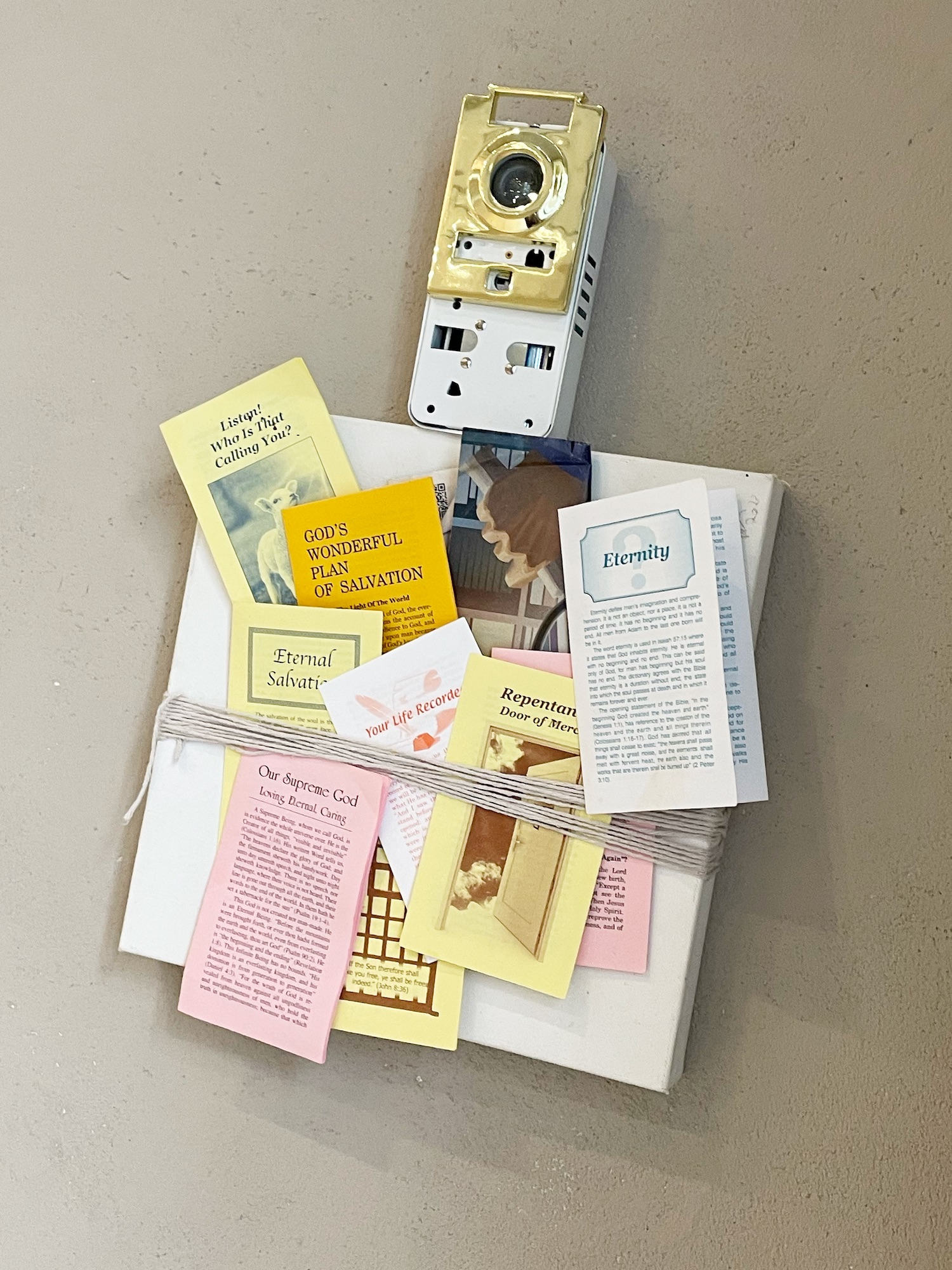

Piccolo Mamuthone, 2019. Reality Show, 2018.

Vilda Krog — When you first picked up a camera, you were "not thinking about art.” Is there a specific space, sequence or image that you could tie the shift to — at what point did the medium turn into the messenger?

Joseph Cochran II— You know when a force is pushing you in one direction? And you ignore it and ignore it some more... You keep ignoring it up until that point when the signs become so prominent that you’re no longer able to run away from it. That’s it.

I was hanging out in Philly a lot, meeting plenty of people who were making pictures, doing creative work. I didn’t have an outlet of my own at that point, and I was constantly trying to find one for myself but kept hitting roadblocks. I pursued writing, creative management, but I never felt truly immersed until one morning after a graveyard shift at the casino I was then working at.

I got home at seven in the morning and wasn’t tired, so I finally picked up that camera-turned-dust-collector and started playing with it. I showed the results to some of my friends, and pretty soon it all made sense — that this had been my medium all along.

You left writing, amongst other mediums, behind?

I still write a lot, mostly for myself though. The reason why I stopped pursuing it professionally was because once I began to use the camera I realized that the lens is just a much stronger way of writing for me. When I looked at the work of some of my early influences, Diane Arbus or Gary Winogrand, I thought, “Wow, these people are doing what I’ve wanted to do in text, through photos.”

I wouldn’t say that I gave up writing, rather that I write in images now.

Listening to you this past Friday, you mentioned your dislike for certain words or used phrases like 'for lack of a better term,' demonstrating the limitations of language as a tool for expression. Have you come across anything a camera can’t explain?

The only element that holds back the camera is the user of the tool, otherwise, it’s completely limitless in terms of expression. There's a quote that I think about by Wolfgang Tillman, perhaps I’m paraphrasing but it goes something like “I can't explain what images do to me.” That’s exactly how I feel about photography.

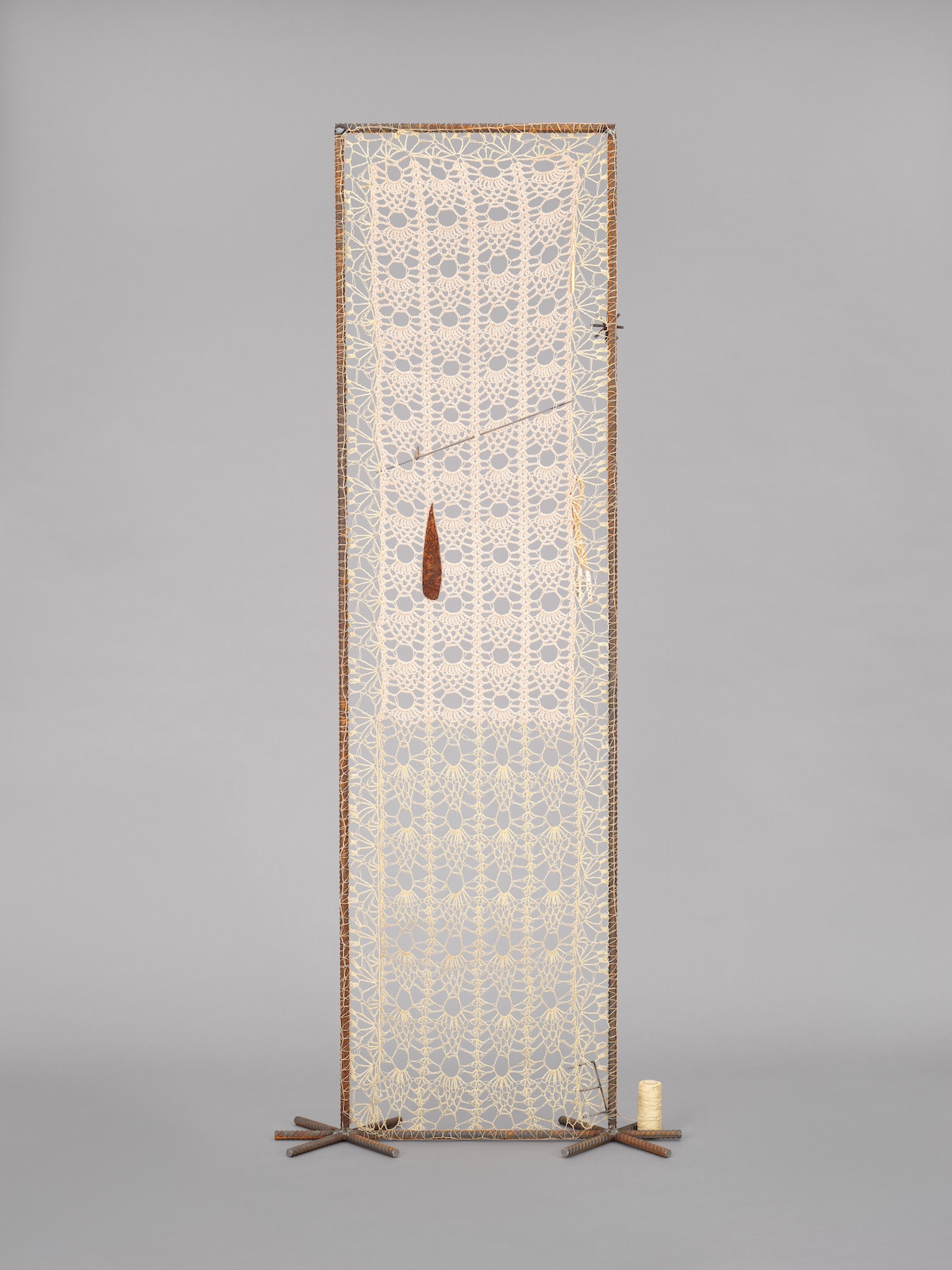

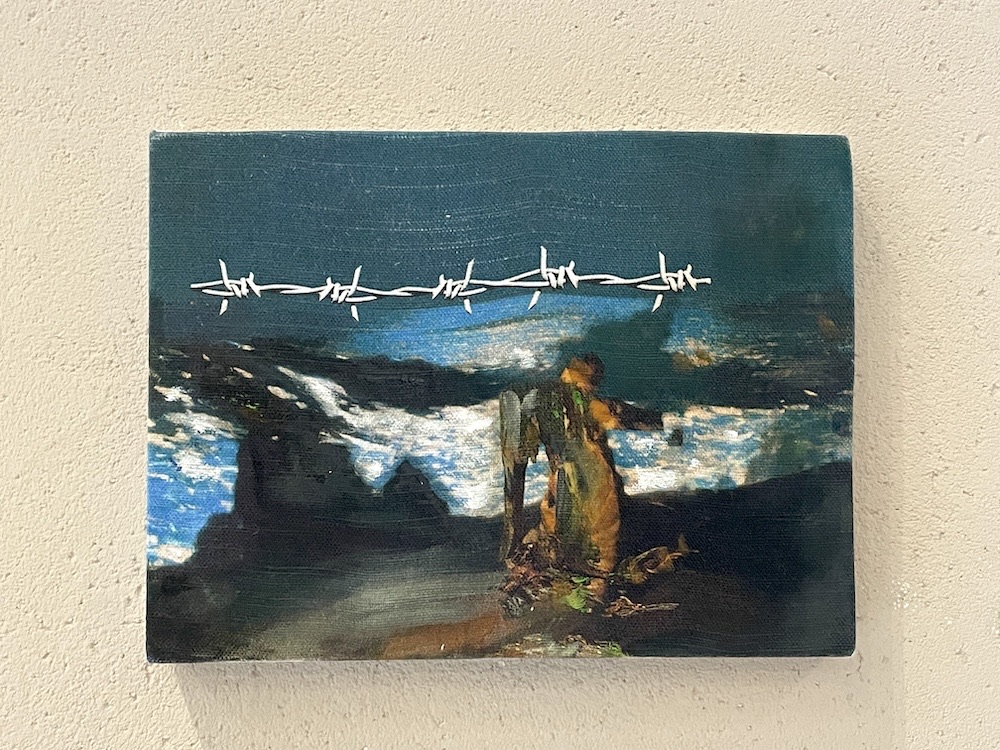

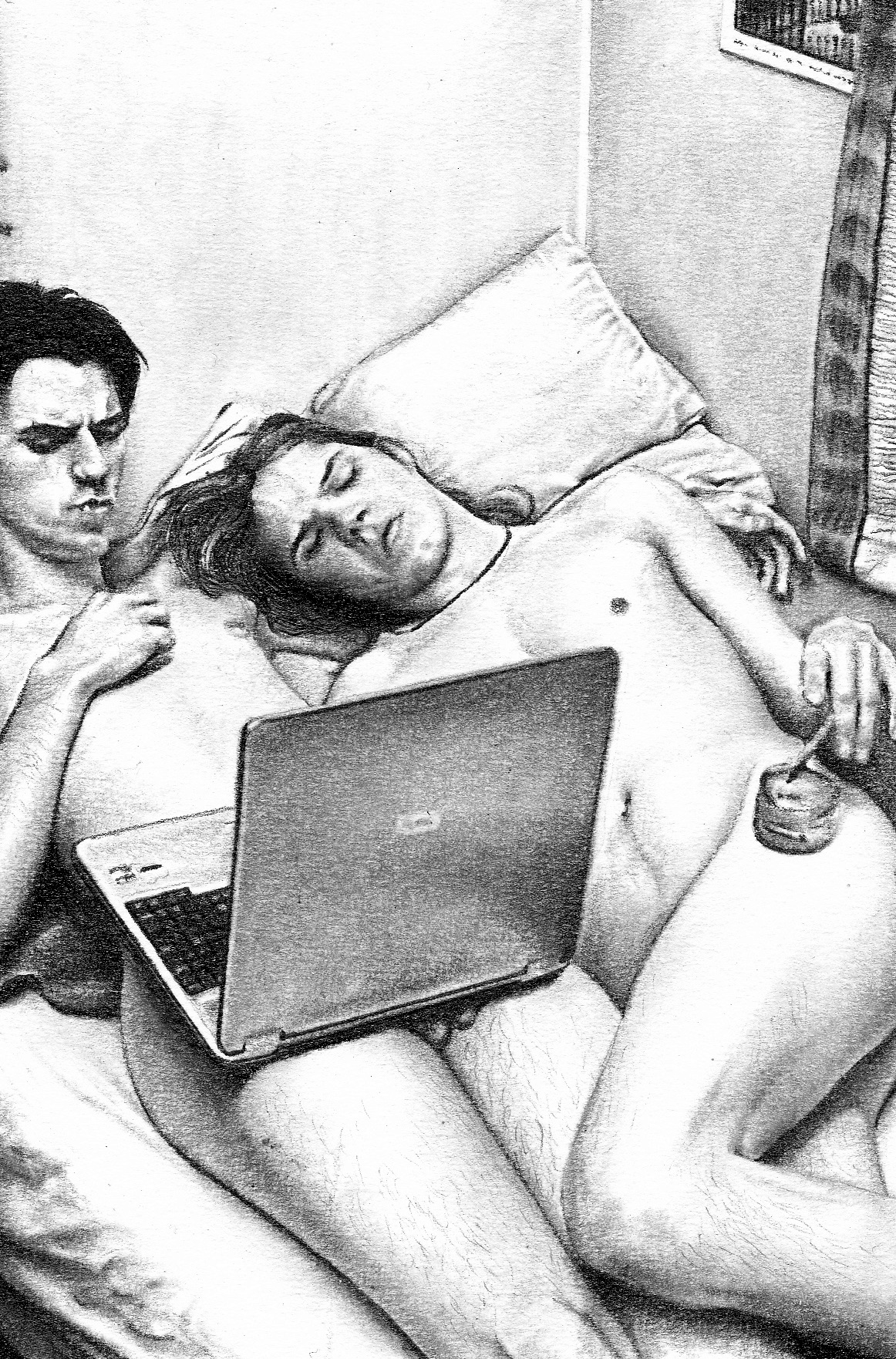

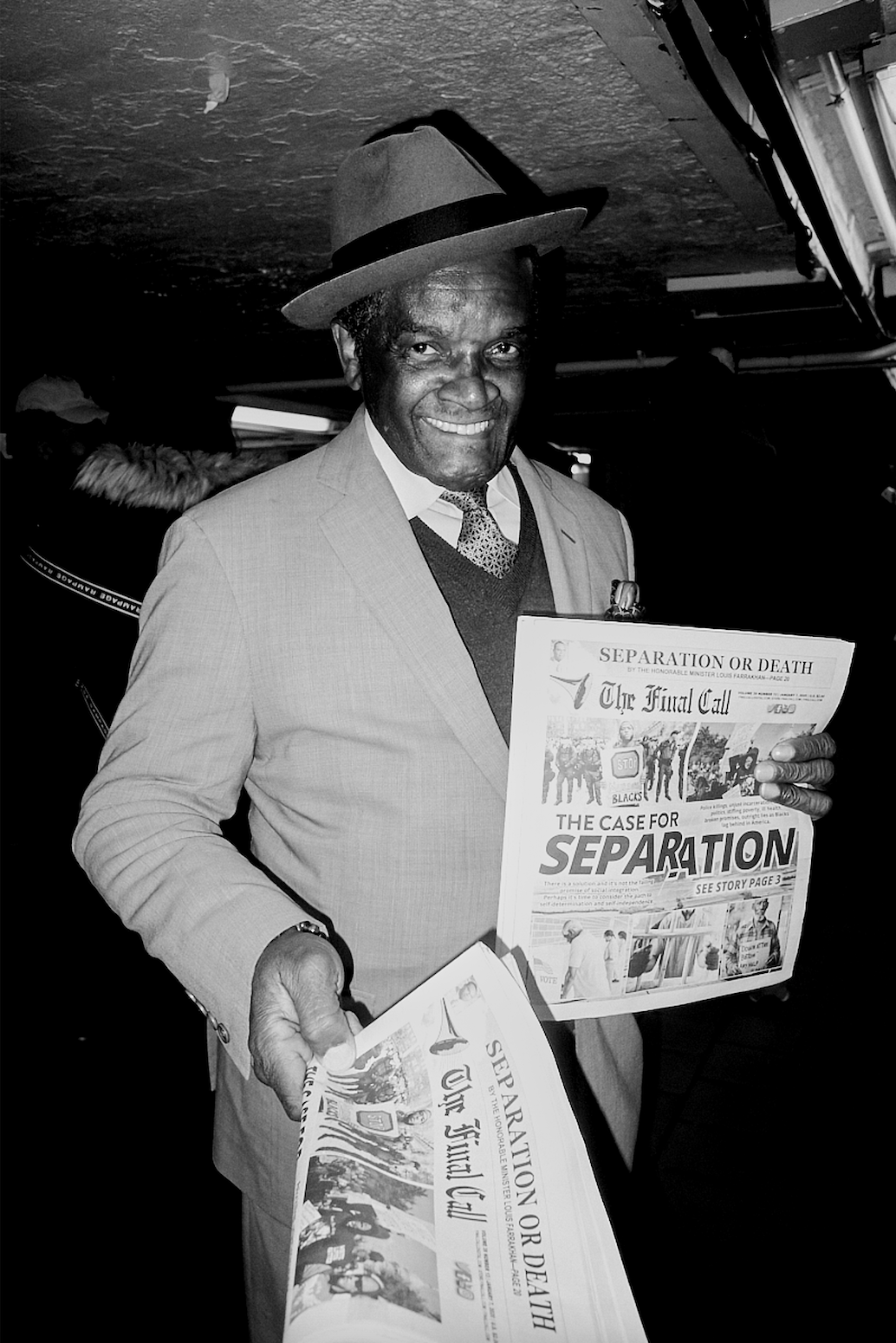

Untitled (April), 2021. The Case for Separation, 2019. Things Fall Apart, 2016.

There are multiple shoutouts when you speak about your work. Yet what I found interesting is that none of the names you mention — Sontag, Baldwin, Debord — are photographers or image-makers. Is it an active choice to pull inspiration and references outside of the visual word? How does that open up avenues in your practice?

I could probably name 30 photographers off the top of my head that have influenced me, and I'll get excited while doing it, but that doesn't mean that I look to them for inspiration on project works. Most of my references are literary because my process comes from a literary space — philosophy, anthropology, and a little bit of fiction as well.

I'm really big on Russian 19th-century literature, and I've been reading philosophy since I was a kid. My grandmother would read me the Iliad and Odyssey, all those Greek and African myths, about the French Revolution, you name it — and I would swallow it as if it was fiction, only to be told that it all had actually happened, that what we were reading was history.

When you look at an artist like Baldwin or Sontag, these people have left behind a Codex as to how to unlock society. It’s coming back to the idea about how to understand contemporary society, taking something that already exists and just changing it by 3% and thereby turning it into something completely different; it’s directly connected to sampling, which correlates to what Virgil Abloh did with Nike, what Duchamp did to art. It’s an interesting avenue, where the whole power sits in the references; the same could be applied to fashion — it’s not about who has access to the finest fabrics, but who has access to the finest books. It all boils down to those who fucking read.

To me, the game is about figuring out — through text, through image research, or through a combination of things — where and how you fit in.

Through this major project of yours, have you been able to discover where you fit in?

I’ve discovered how deeply I care about humanity and how I care about the whole of it more so than the micro or the exclusive. I am interested in the spectrum of society, the good, the bad, and the ugly, and through the camera, I can empathize and relate to it all. In my formative years, I thought that I didn’t fit anywhere, that I was an anomaly in a sea of normalcy. Today I recognize this as a positive, but it certainly did not feel this way in the beginning.

My experience as an at-risk youth in New York City, whisked away from my family made me think I wasn’t loved, wasn’t wanted. It took living on four different continents, falling in love, falling out of love, immigration — all of the substantial experiences I encountered over the years documented in this book to realize that all the love I ever needed was provided — it was in me and always around me, I just needed to open my eyes.

My father never had the opportunity to leave New York unless it was in chains, my mother and grandmother never had moments of respite in their lives, and in my grandmother's case, she never will. They were born into an unfortunate cycle of government-sanctioned domestic terrorism. This work revealed to me that I am the hope of my family, I embody the wishes of my ancestors for us to be more than the cards we have been dealt.

Perhaps the biggest discovery for me, is that I will never stop making this work — it is what liberated me and gave me my mission — to witness humanity in its entirety, telling not only my story, my mythology, but those of my family, and others who trust me with theirs. Whether my friends or family, refugees, my Muslim brothers and sisters, and others I’ve crossed my path with. I saw them and their stories as important, and integral to what will be the history of our time. I’ll honor them today and tomorrow, and after the day I’m gone.

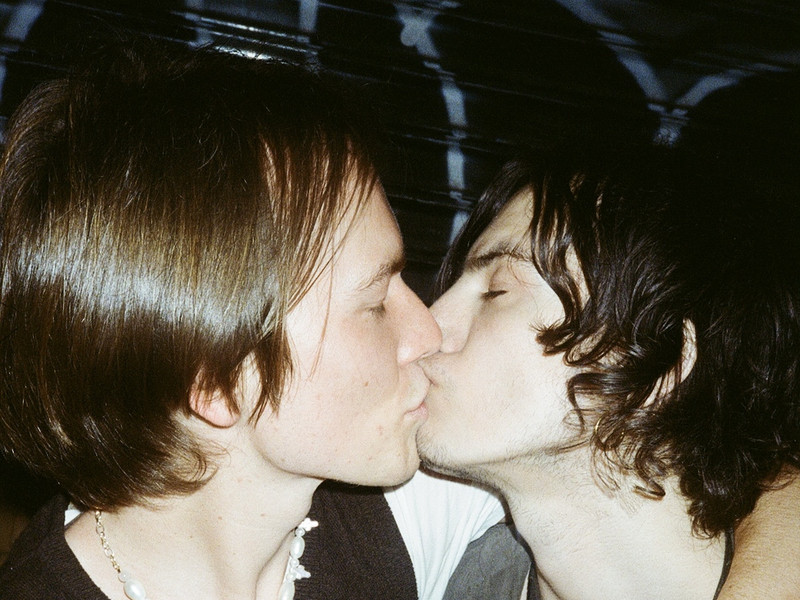

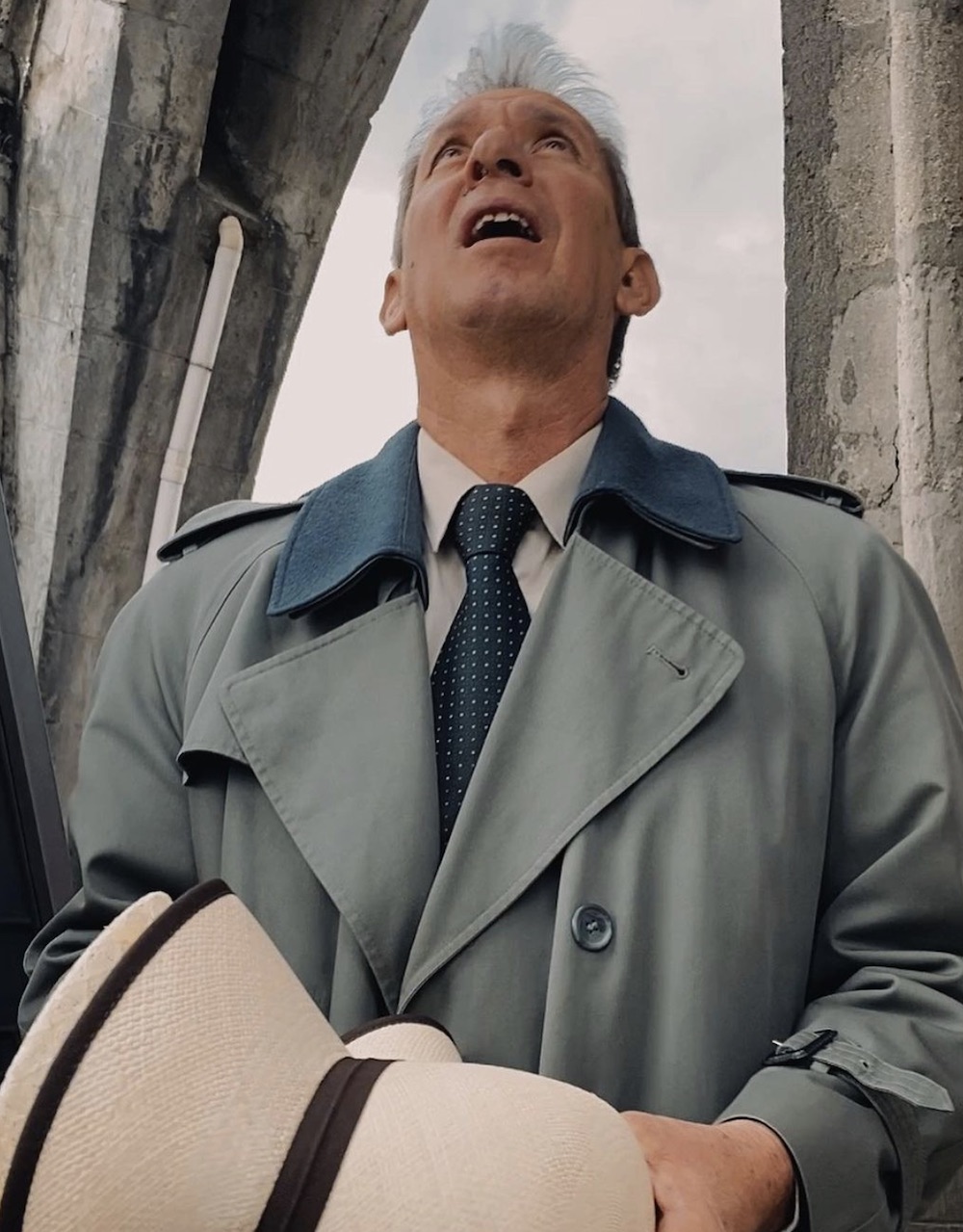

Home for Migrants, Nuoro, 2018. Uptown, 2019.

Listen to the full conversation from the release at Printed Matter, supported by Dirty Magazine and Uncensored New York, here.