X'ene's Witness: Justen LeRoy's Black Environmentalist Sonic Vision

“There are all these vocal nuances that happen in between a phrase – the notes, the runs, the melisma that connects the emotion from one word to another,” LeRoy explains. “But that note is carrying so much information, like how we can hear Jazmine Sullivan riff without saying one word, but we know exactly what she means. What is inside of that?”

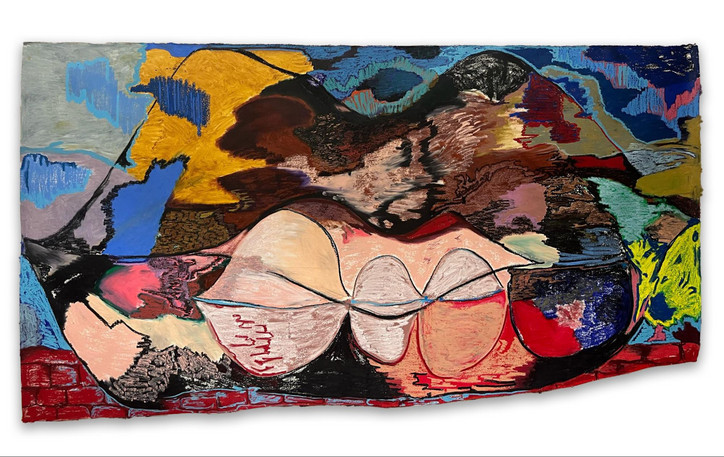

Thinking alongside renowned cultural theorist, poet, and scholar Fred Moten, LeRoy was struck by the concept of the “wordless moan.” In his essay “Black Mo’nin,” Moten references The Gospel Sound, a text by gospel producer and writer Anthony Heilbut. “The essence of the gospel style is a wordless moan,” Heilbut writes. “Always these sounds render the indescribable, implying, ‘Words can’t begin to tell you, but maybe moaning will.” “Lay Me Down In Praise,” which was exhibited as part of a collaboration between the California African American Museum and Art + Practice, drew connections between gospel’s wordless moan and the “moans” emitted by the earth amidst anthropocentric climate abuse, from the sounds of the ocean to the rustling of the trees.

Building on the foundations of his first exhibition, X’ene’s Witness sought to “build a portal” for LeRoy's community to engage in conversations about climate change – conversations that Black communities are often excluded from, despite disproportionately bearing the brunt of damage from environmental forces like air and water pollution. “I live in South Central, and almost nobody here is thinking about climate change because they’re thinking about everyday survival, how to feed their kids and how to get to work,” he says. “I'm always thinking about their access to the message.” This resolve to foreground accessibility in his work is why it was so important for LeRoy to show “Lay Me Down In Praise” in Leimert Park, a predominantly Black neighborhood in Los Angeles.

LeRoy’s own introduction to the fine art world was rather unorthodox, as was his path to becoming a working artist in his own right. During his freshman year at UC Irvine, he discovered writer and curator Kimberly Drew’s “Black Contemporary Art” Tumblr blog. “She was just sharing her interests and her knowledge, and it opened up a pathway for me, a sense of possibility,” LeRoy recounts, “to know that this world existed, and that I could situate myself in it.” He subsequently enrolled in art classes, but was disappointed to find that he was still learning more from the bloggers he found online than he was in the classroom. In 2015, he visited his first contemporary museum at the age of 20; by September of that year, he was working as a gallery attendant at the Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown Los Angeles; soon after, he joined the now-closed Underground Museum, where he would spend six years working in various positions and interfacing with artists including Khalil Joseph, Deana Lawson, and Henry Taylor. “But I would definitely say that music came first for me,” he says. “I was a really obsessive kid when it came to buying CDs. I still love the tangibility of it all, the research and all the liner notes.”

In 2019, LeRoy finally decided to follow his own long-held creative impulses, performing at MoMA PS1 with British composer and playwright Klein, who he credits for the final push into pursuing an artistic career of his own. “I will thank her forever for opening that possibility for me in a moment where I wasn’t sure,” he says. “She really helped me see myself.” LeRoy continued to explore his fascination with R&B music and the tradition of Black sound, and his audio work “Leave A Message” was featured in the Hammer Museum’s 2020 exhibition “Made in LA.” Alongside creating his own work, he is now the Director of Public Programs and Community Outreach at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

LeRoy’s years working for galleries and museums have left him well-equipped to deliver on his accessibility goals. “I'm thinking about the audience first,” he describes. “I'm definitely making work for me, but I want to have a conversation, I want to make sure that the work can survive in a public programming setting, and that there are different pathways to interact with it.”

“Having been on the other end of doing insurance reports and communicating with people about getting work shipped and interfacing with the public daily and seeing how things get funded and made – there’s a lot that’s at the heart of the success of an exhibition,” he continues. “I’m working with a lot of dancers and singers, and I want to help demystify what the art world is and how it works by bringing collaborators into it who have never been centered in it, and help them navigate funding resources for their work too. Hopefully that sets a standard, for how we create a moment, how we create eras, how we usher new artists in.”

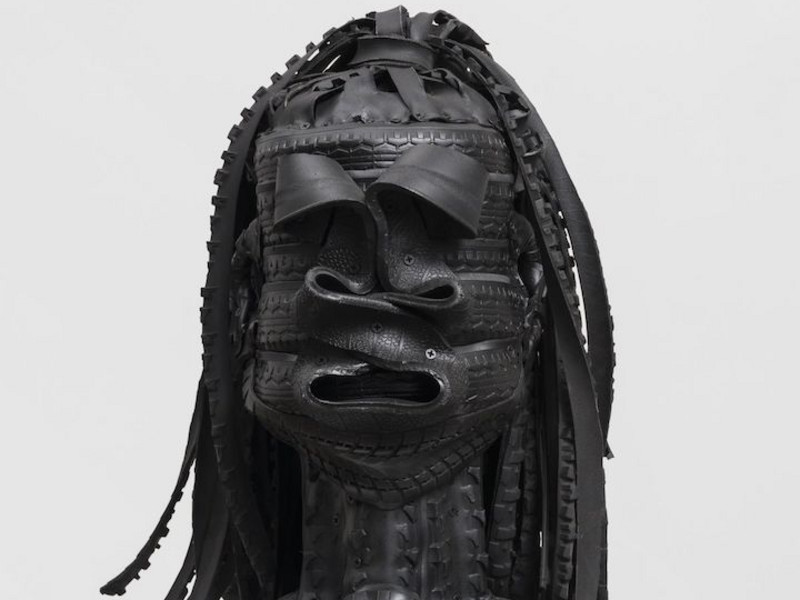

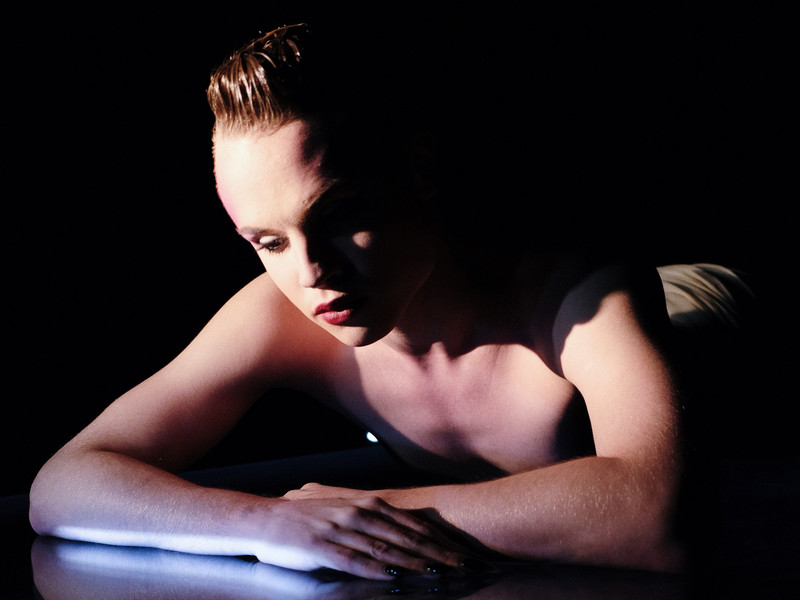

X’ene’s Witness, which held two free performances on November 17th and 18th, is the culmination of a decade’s worth of collaboration and creative respect. LeRoy and his co-composer Alexander Hadyn have worked together since LeRoy was 18 years old. “We’ve learned so much from each other,” LeRoy says. “He’s my right-hand guy.” He describes performance artist and classical musician X’ene Sky, from whom the opera takes its name and its voice, as his “sister”; costume designer Corey Stokes as “one of my best friends”; creative director Franc Fernandez as a “legend”; and describes himself as a “longtime fan” of movement director Qwenga. “This piece is a combination of so much of our collective thinking and ideas,” LeRoy says. “I’ve never done anything like this before – my career as an artist is very young, and it’s a big leap. There’s a lot of surrendering taking place right now. I brought everybody into the fold because I have so much faith in what they do as individuals.”